The Other Monument

Published May 26, 2022

The holiday weekend approaches at a time that I am sure we could all use a break.

To many, this weekend always marks the unofficial beginning of summer. To be frank, after the topsy-turvy, extra Midwestern exploits of a drunken Mother Nature this past “spring”, the arrival of summer is most welcome here in Kansas City. And while, by all means, we should make the most of and enjoy this weekend, it is imperative to take a step back, take a breath, and give ourselves a moment to remember why we have this weekend to begin with.

“... we do know they summed up and perfected, by one supreme act, the highest virtues of men and citizens. For love of country they accepted death, and thus resolved all doubts, and made immortal their patriotism and virtue.”

Since 1971, Memorial Day has been a federal holiday that is observed on the final Monday of May in order to honor those soldiers who have fallen in service to this country. However, this ritual goes back more than a century before Congress made it an official holiday. In 1868, General John A. Logan, the leader of a group of Union Army veterans known as the Grand Army of the Republic, decreed that May 30 should become a day of commemoration for all of the soldiers killed in the American Civil War. He named the holiday Decoration Day, as he envisioned it as a day for laying flowers on the graves of these soldiers.

Some believe that Logan chose this date because it did not conflict with the anniversary of any Civil War battles. Most suggest that it was due to a belief that flowers would be in bloom all across the nation at this time. Regardless, Americans embraced the notion and the majority of states soon adopted Decoration Day as a holiday to honor fallen Civil War soldiers. After America’s entry into The Great War (World War I) in 1917, with feelings of patriotism at a high, the holiday was expanded to be a day to honor ALL fallen American soldiers.

In the same way that World War I was a catalyst for Decoration Day, now Memorial Day, eventually becoming a national holiday, it also sparked something in Kansas City - a civic identity.

In the early 20th Century, the city was thriving! The agriculture sector was experiencing exponential growth and with Kansas City’s many agrarian businesses, it benefitted from the boom. Reaping the benefits of being so geo-centrally located, Kansas City was a hub of transportation and distribution. As a result, the city had a burgeoning middle class that was growing larger by the day and was a breeding ground for entrepreneurship. During World War I, Kansas City continued to flourish as the Garment District outfitted the military and local farmers fed them. Newly-constructed Union Station became a common pitstop for soldiers as they were sent to training and sent to the war front.

When the war ended in November 11, 1918, Kansas City was enjoying an era of economic prosperity unlike anything the city had seen prior or since. Despite being at the height of the Spanish Flu pandemic, it is reported that when the war officially ended, over 100,000 people flooded the streets of downtown and threw an impromptu parade in celebration.

In that response, city leaders saw an opportunity. Within weeks, the Liberty Memorial Association had been formed to find a way to honor those who served, and those who fell, in the The Great War. And in 1919, when they launched a fundraising campaign for a memorial to those soldiers, Kansas Citians raised the modern-day equivalent of $35 million - in only 10 days! In that one act, our city found an identity and showed a graciousness and generosity that continues to this day.

And today, Kansas City is known by many as the home of the Liberty Memorial and National World War I Museum - the only national war monument NOT located in Washington, D.C. For locals, this pillar of limestone that towers over downtown Kansas City is one of our most-recognized landmarks. The memorial, its terrace, and its lawn, are, without question, the most photographed area in the city. It is the most sought-after view of the city by locals and visitors alike. Nearly every U.S. President since Calvin Coolidge, as well as over 600,000 people each year, have visited the Liberty Memorial. And on Sunday night, thousands more will flock to the monument’s lawn to enjoy holiday fireworks above Union Station.

And if your Memorial Day weekend plans include paying a visit to the Liberty Memorial to pay your respects, then I would tell you that is a fantastic idea. But I would also guess that, if you’re from here, you’ve been there before.

So why not pay a visit to a beautiful, towering, ornate stone monument, built in the 1920s, with a phenomenal view of downtown Kansas City that is dedicated to local soldiers who served this country during World War I?

I am not talking about Liberty Memorial. I am talking about the other monument. The one you probably haven’t visited. The one you might have never even heard of.

If you’re from Kansas City, the truth is that you have probably driven past the Rosedale Memorial Arch hundreds of times and never once noticed it. If you know what you’re looking for, it is visible from the downtown stretch of I-35 but even then, it can be a little hard to find. Sitting tucked among the trees atop Mount Marty, less than three miles from Liberty Memorial, is a grand stone archway forever dedicated to the men of the Rosedale neighborhood of Kansas City, Kansas who served during World War I.

The overlooks at the Rosedale Memorial Arch offer an incredible view of downtown Kansas City, Missouri.

In 1917, the world was at war. The United States had not yet joined the fray in Europe but the writing was on the wall. In April of that year, President Woodrow Wilson had appeared before a joint-session of Congress to formally request that the United States declare war on the Central Powers (Austria-Hungary, Germany, and Turkey). Two months later (June 1917), a group of over 350 men from Rosedale and the surrounding area gathered at the top of Mount Marty to be sworn in to the United States Armed Forces. At this time, Rosedale was not a neighborhood at all but a small municipality of its own that was completely independent of KCK. The majority of those enlisted in Rosedale on that day were assigned to the 42nd United States Infantry. When the United States officially declared war later that year, this group was deployed to France.

The 42nd Infantry was a collection of over 28,000 National Guard troops from 26 states. This unusual composition lead Secretary of War Newton Baker to nickname the group, “The Rainbow Division”. The Rainbow Division were known for their toughness in battle, adept in trench warfare (thanks to the tutelage of French troops), and tasked with shoring up the western front. They were the only American battalion to fight alongside the French Fourth Army, who was led by the legendary, one-armed commander, General Henri Joseph Eugene Gouraud. Alongside General Gouraud and his men, the Rainbow Division saw a lot of military action. They were an integral part of expelling German forces from France and pushing them back towards Belgium. Most famously, the division fought in the 4th Battle of Champagne and were involved in the Battle of Argonne Forest - the final battle of World War I. During those two years of battle, the Rainbow Division suffered over 16,000 casualties - nearly 60% of their original enlistment.

“In fact, Rosedale’s monument nearly went ... unrealized.”

Six months and a day after the war ended, on May 12, 1919, the Rosedale community lined the streets and held a parade to welcome the men of the 42nd United States Infantry home. One of Rosedale’s major thoroughfares, Hudson Road, was renamed Rainbow Boulevard in their honor. In the years that immediately followed, efforts were undertaken on both sides of Stateline to pay tribute to the veterans of The Great War. Feelings of national pride and patriotism that had swept the nation were particularly strong in this region. As already mentioned, the funds for Liberty Memorial in Kansas City, Missouri were raised in 1919. After the Kansas Legislature passed a measure in 1921 permitting cities to issue bonds for the purpose of memorials to the war, 63% of Rosedale voters voted in favor of issuing a $25,000 bond (over $400,000 today) to erect a monument to those from Rosedale who served.

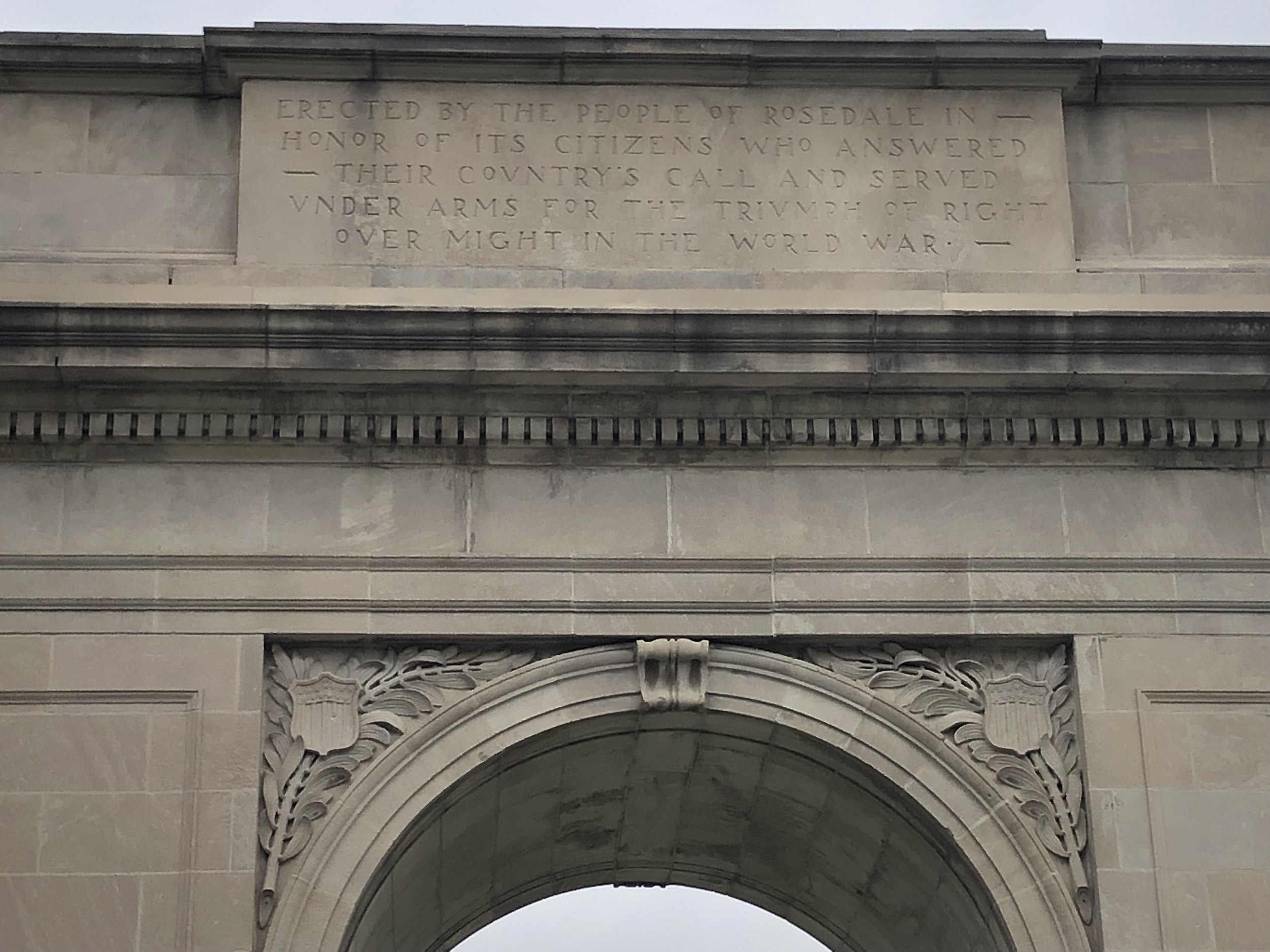

The parapet of the Rosedale Memorial Arch.

Afterwards, a committee was formed to oversee the project. They began the process of securing an acreage atop Mount Mary, the site of the Rainbow Division’s enlistment ceremony, for $10,000. Rosedale’s own John L. Marshall, a World War I veteran and a member of the Rosedale American Legion, volunteered his services to design the proposed monument. Marshall was among the first students to ever attend the architecture school at the University of Kansas but dropped out after a couple of years in order to enlist. During the war, he had been stationed in France and spent much of his free time sketching what he saw there. Many of these sketches were of the famed Arc de Triomphe in Paris, which became the inspiration for Marshall’s masterpiece.

The committee approved Marshall’s design. They envisioned his monument not only as a memorial but as a gateway. The arch would be built on the north end of the Mount Marty plot, overlooking Turkey Creek, and it would give way to a sprawling public park and athletic fields on the remaining lot adjacent to Rosedale High School. This aspect of the vision would never be realized. In fact, Rosedale’s monument nearly went similarly unrealized.

In April of 1922, Rosedale was annexed by Kansas City, Kansas and incorporated into the city. This shift from an independent municipality to a neighborhood in Kansas City, Kansas threated to permanently terminate the project. Given Rosedale’s change in status, the validity of the bond passage was in question. While the debate waged, Rosedale lacked the ability to sell the necessary bonds and the future of this monument hung in the balance. It felt like it would never be built.

Fortunately, former Rosedale city attorney Louis Gates was now a member of the State Legislature and he introduced a measure that amended the original bond passage in a manner that would permit Kansas City, Kansas to sell the bonds and move forward with construction. In February of 1923, the measure passed and Kansas City, Kansas was given approval to begin selling the bonds. Astonishingly, the project which once felt dead in the water had only been delayed by about two years.

Rosedale Arch, and nearby Rainbow Boulevard, are dedicated to the memory of Rosedale’s “Rainbow Division”.

On July 19, 1923, the city of Kansas City, Kansas began issuing Rosedale Memorial bonds. The following day, a groundbreaking ceremony was held atop Mount Marty. It included a parade the likes of which KCK has not seen since. It stretched from 39th Street to Mount Marty. General Henri Joseph Eugene Gouraud, commander of the French Fourth Army, who fought alongside the Rainbow Division was the guest of honor. He presided over the ceremony, with the assistance of an interpreter, and was the first to break ground on the memorial, with a golden spade. A number of other dignitaries were in attendance and made remarks including Kansas’s governor, mayors of both Kansas Citys, as well as congressmen from Kansas and military representatives from Fort Leavenworth. All told, more than 6,000 people were in attendance for the groundbreaking - over twice the population of Rosedale!

The arch would incur a few more delays, related to finalizing the purchase of the lots for the memorial. In the Spring of 1924, construction, overseen by H.C. Readecker, a stone mason from Rosedale, began. Once it did, it went swiftly and was completed in less than four months! With a final cost of $12,179.00, combined with the $10,000.00 for the land - the price tage of $22,179.00 means the monument actually came in 12 percent under budget.

Marshall’s inspiration from the Arc de Triomphe is quite evident, although the Rosedale Memorial Arch is definitely a scaled down version. It has often been compared to New York’s Washington Square Arch, which is still twice the height of Rosedale’s. The classical-style arch is constructed of brick with a four inch thick façade of limestone plates. It stands 34.5 feet tall, 25.5 feet wide, and is 10.5 feet deep. The pillars of the archway are blank. It was intended for the names of Rosedale’s WWI soldiers to be inscribed on these plates, but that never came to pass. Upon the parapet, the arch bears an inscription -

ERECTED BY THE PEOPLE OF ROSEDALE IN

HONOR OF ITS CITIZENS WHO ANSWERED

THEIR COUNTRY’S CALL AND SERVED

UNDER ARMS FOR THE TRIUMPH OF RIGHT

OVER MIGHT IN THE WORLD WAR.

On September 7, 1924, the arch was dedicated. While the ceremonies did not reach the grandeur or fanfare of the groundbreaking, an estimated 2500 people were in attendance. Kansas City, Kansas mayor W.W. Gordon, Rosedale School Board President Frank Rushton, and Brigadier General Harry A. Smith, Commandant of Fort Leavenworth, addressed the crowd. While Rosedale was no longer a city of their own, her people was, at last, able to have a lasting reminder of their heroes and the Rainbow Division for all to see and enjoy for all time.

In 1993, this tablet, which bears the name of Rosedale soldiers who lost their lives in combat, was added to the memorial.

Or so it was thought. Tragically, the Rosedale Arch quickly faded from collective memory, and into near-ruin. During the Great Depression, the Arch was isolated. The committee’s hopes of a sprawling park were stamped out by the Works Progress Administration (WPA) constructing a new athletic field for Rosedale High School that cut off access to the arch entirely. The school’s baseball field is still there today and the stone retaining wall for the park makes it difficult to spot the Arch that is right next to the outfield wall. This poor planning by the WPA led to the Arch being “virtually forgotten, unvisited, overgrown with weeds, grass, and brush, and slowly deteriorating”* over the next few decades.

Fortunately, in 1962, a Rosedale WWI veteran raised the issue of the Arch’s condition to city officials. The city responded by raising funds to restore the arch, cleaning up the area, and constructing a new access road to the memorial. On Veterans Day of that year, the Rosedale Arch was dedicated to Rosedale veterans of all wars. However, the reactionary response would not be lasting. It was not until 1972, when the arch was included in the city’s parks improvement program, that it began to feel like the Arch’s future may be secure.

That year, the city finally paved the access road that had been constructed ten years prior. The area was once again cleaned up and additional improvements were made. Flood lights were installed to properly illuminate the arch at night. A plaza was constructed that contained benches and walkways, as well as overlooks that provided breathtaking views of not only Rosedale but of downtown Kansas City, Missouri. Parking spaces for visitors were installed at the top of Mount Marty. In 1974, the fiftieth anniversary of the Rosedale Memorial Arch’s construction, it was re-dedicated during a ceremony on July 4. In 1976, to ensure the long-term viability of the Arch, and not repeat past mistakes, Rosedale residents applied for it to be included in the National Register of Historic Places. That request was granted and the Arch’s future was finally secure.

Since that time, the Rosedale Memorial Arch has been carefully maintained by the parks departments of Kansas City, Kansas and Wyandotte County. In 1993, a small marker, which stands in stark contrast to the monument, was installed underneath the arch to honor those Rosedale residents who died in service to their country during World War I, World War II, the Korean War, and the Vietnam Conflict. Improvements have been made in subsequent years that make this monument accessible by foot, bicycle, car, and ADA (American Disabilities Act) friendly as well. Today, the Arch remains a testament to those brave local men and a reminder of small but proud city turned Kansas City neighborhood.

Over the years, a number of improvements have been made to make the Rosedale Memorial Arch more accessible to all. PHOTO CREDIT - LeAnn Sarah Photography

“The Rosedale Arch has become an identifying landmark of a community which was swallowed up by urban expansion. Its simple but dignified form rises from Mount Marty, addressing and framing the Kansas City skyline.”

In 1971, five years prior to the Rosedale Arch receiving federal protection, the United States Congress realized General John A. Logan’s dream of making Decoration Day a federal holiday. Unlike Logan’s iteration of the holiday, it was now widely known as Memorial Day and a day to remember veterans of all United States wars, not just the American Civil War. It also no longer fell on May 30. Due to legislative action in the late sixties, Memorial Day was shifted to the final Monday of the month, regardless of the date. The move was rife with controversy then, and even now, as many veterans groups worried that the move from May 30 would lead many to see Memorial Day as a three-day weekend that begins summer and not for its intended purposes. Fifty years later, it could be argued that these concerns were warranted. However, this year provides the benefit of Memorial Day actually falling on May 30, something that will not happen again until 2033.

This season, Sporting Kansas City’s (MLS) secondary kit featured a crest of a shuttlecock (Nelson Atkins) superimposed over the Rosedale Arch that left many fans wondering, “what is that arch thing?” Slowly but surely, Kansas Citians are learning.

The great tragedy of the Rosedale Arch is how quickly it fell into obscurity, and then how it seemingly, suddenly, fell into obscurity again and again! Even today, while new life has been breathed into the monument, it remains largely unknown and ignored by Kansas Citians. Similarly, many once feared that the movement of Memorial Day from May 30 would cause many to forget what this holiday is all about.

So as Memorial Day weekend approaches, enjoy the opportunity to take a much deserved break, to enjoy some time with family and friends, and have all the fun that comes with a summertime three-day weekend. Feel free to celebrate the arrival of summer. But before you do all those things, take the time to remember how lucky we are to all live in a city as marvelous as this one. Remember that, in spite of our many problems and up-and-down past, that we do live in a great country.

In recognition of that, consider making the trip to the top of Mount Marty and visiting our city’s other World War I monument for yourself; the one you may have driven by a thousand times and never noticed. Take in the beauty of this classic archway, relish the serenity of the small bluff-top park, and embrace that wonderful view of our city.

And while you are doing that, pay your respects to the brave men from our community who fought to free Europe from tyranny. Read the names of those under the Arch. Remember those local young men who paid the ultimate price so we could continue to live in a city as great as ours.

Even if you cannot find your way to the Arch this weekend, be certain to take a moment, or several, just to remember. After all, this is the actual reason for the holiday.

Those Pesky Endnotes That I Often Insist Upon

*Per the National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form for the Rosedale Arch in 1976.

The 411

Rosedale Memorial Arch

3602 Springfield Street

Kansas City, Kansas

HOURS: 7 Days A Week, 5:00AM - 10:00PM

For information on how you can contribute to the preservation of this monument, please check out the Rosedale Development Association (RDA)!