blaKC (4/5)

Now named the John Buck O’Neil Center, the Paseo YMCA was the site of the founding of the Negro National League in 1920. PHOTO CREDIT: LeAnn Sarah Photography

Published February 22, 2021

A NOTE FROM THE WRITER: This particular edition of “flashbaKC”, in celebration of Black History Month, is the fourth chapter of a weekly, five-part series that explores some of the stories of the amazing black men, women, and entities that shaped our city, and overall society. I STRONGLY ENCOURAGE YOU TO READ CHAPTER III BEFORE READING THIS CHAPTER. Writers write for a handful of reasons. For the month of February, I have chosen to just tell stories. Whether you are entertained, persuaded, or informed? Well, that’s up to you.

Please, be mindful that due to COVID-19 concerns, some of the places recommended in this article may not be open to the public, or have limited hours and capacity.

-ning, and spinning, and spinning towards the plate. The bat swung, and then, CRACK!

Before I could even comprehend what I was seeing, the ball quickly flew over Lorenzo Cain’s head as it sailed past the centerfield wall. Brandon Moss had hit his second homerun of the game; a three-run shot off Yordano Ventura. Derek Norris and Coco Crisp would both follow with RBI (Runs Batted In) singles. The Kansas City Royals trailed the Oakland Athletics 7-3 at the end of the sixth inning of the 2014 American League Wild Card Game.

There I sat, dejected, in Section 425, Row S, Seat 1 with my hands covering my face. I let out a deep breath, sat up, and turned to my right,

“We’re not leaving. No matter how bad it gets. We’ve waited 30 years for this, and we are NOT leaving.”

A quick, silent nod from my friend Jon told me that he both understood and felt exactly the same way. Our sentiment was clearly not unique. The sea of blue that engulfed Kauffman Stadium stayed in place. Not a seat was empty. Collectively, we had all waited too long for this moment.

With no way of knowing that I was about to see something special, I took a minute to absorb it all and make a memory. The lights. The crowd. The stakes. The energy. The city had not seen October baseball in 29 years and did not know when we would again. Looking across The K, I knew that regardless of the outcome, I was already seeing something special.

There was something in the air that I cannot quite explain. It just felt like playing under the lights, on the biggest stage, suited Kansas City. In that moment, I knew.

Kansas City was born for this.

Kansas City was meant for this.

Kansas City invented this.

Chapter IV: Second Class Immortals

“A gentlemen’s agreement.”

That’s what they had the audacity to call it, when it was spoken of at all. There was no official rule that prevented African Americans from playing in the Majors. In fact, in the 1880s, Major League Baseball’s (MLB) first black player, Moses “Fleet” Walker, had played for the Toledo Blue Stockings. However, since Fleet had hung up his cleats around 1884, it was widely understood by team owners that blacks would not, and could not, play. Like many Jim Crow policies, this discrimination was constructed on a series of winks, handshakes, head nods, and “common courtesy”.

A gentlemen’s agreement? Psch. There’s nothing gentlemanly about exclusion.

“We are the ship; all else the sea.”

Segregation in baseball led to the creation of all-black barnstorming baseball teams in the early 1900s. Barnstorming refers to teams that traveled from town to town to play in exhibition games. Since these teams existed independent of any league, they played against local teams, or against each other, on any field around the country that would have them.

In the early barnstorming era of black baseball, few figures loomed larger than Andrew “Rube” Foster. When Foster’s playing days ended, he transitioned from pitching for the Chicago American Giants to owning and managing them. Foster dreamed of a better future for the sport and had a vision for what black baseball could be.

On February 13, 1920, Rube Foster and the owners of seven other black baseball teams met at the Paseo YMCA in Kansas City, Missouri. The meeting had been billed as a preliminary discussion on forming an all-black league to rival the Major Leagues. Little did the other owners realize that Foster would show up with a charter and constitution for this new league already in hand. By the end of the meeting, all eight owners had signed on and the Negro National League (NNL) was born.

The League’s first season featured Foster’s Chicago American Giants, the Chicago Giants (not a typo!), the Cuban Stars, the Dayton Marcos, the Detroit Stars, the Indianapolis ABCs, the St. Louis Giants, and the Kansas City Monarchs.

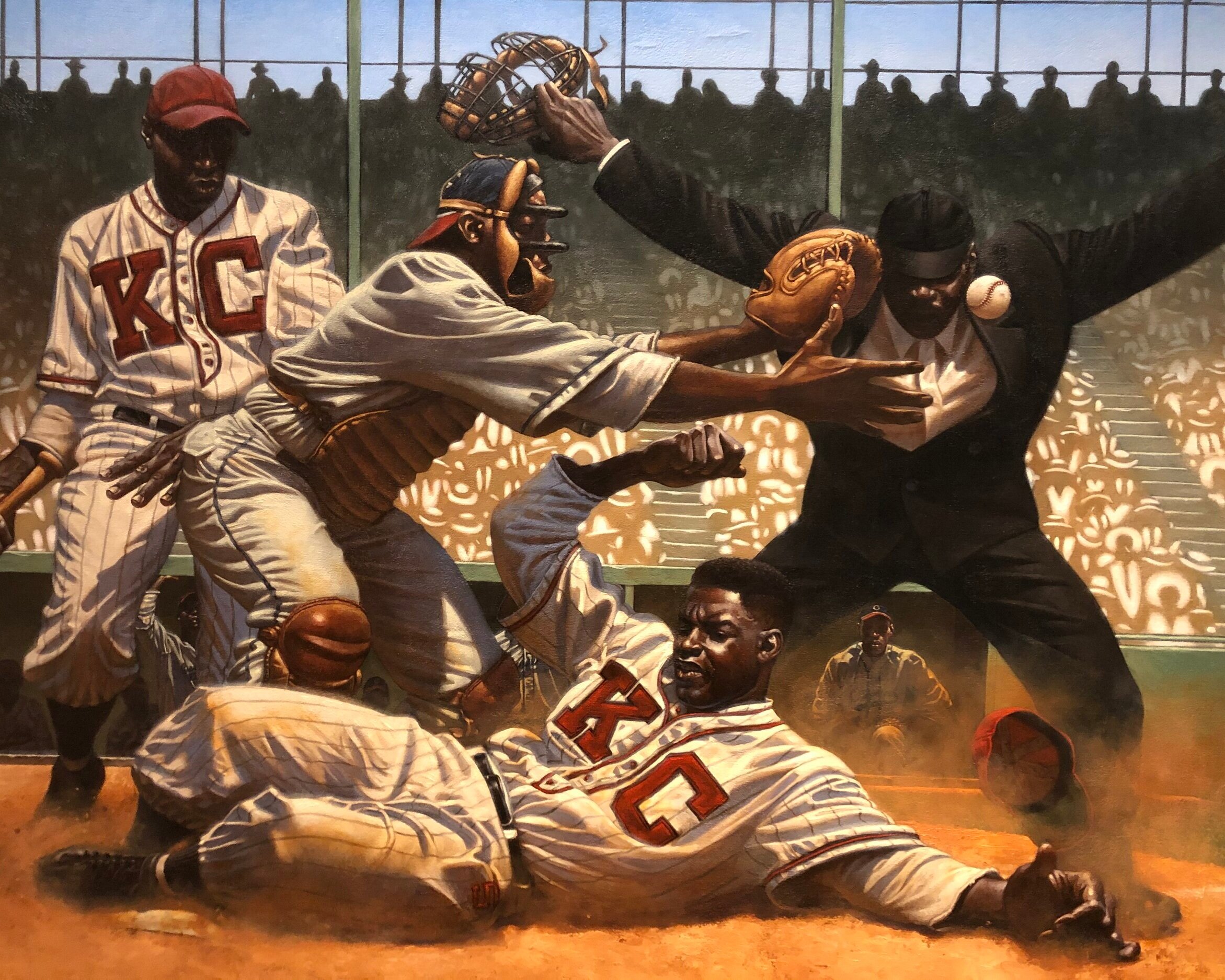

The Kansas City Monarchs, 1920s. PHOTO COURTESY OF: Negro Leagues Baseball Museum

Inventors of Primetime

The Kansas City Monarchs (1920 - 1955)

J.L. Wilkinson’s Kansas City Monarchs began play at Association Park in 1920. Wilkinson, the only white owner in the league, had notoriously fielded interracial barnstorming teams, in a time when that was unheard of. The best players from that team, his Des Moines-based All Nations team, were the foundation for the Monarchs’ inaugural roster. He rounded out the roster with players recruited from the United States Army’s all-black 25th Infantry Wreckers ball club.

“When I got to know [J.L. Wilkinson], I realized I was in the company of a man without prejudice, the first man I had ever known who was like that.”

Wilkinson could not have cared less about the color of a person’s skin, or their nationality, but he did care what kind of ballplayer they were. He did care about winning. Luckily, the Monarchs were successful from the start. They were an immediate hit! The Kansas City Sun reported after the 1920 season that, “One hundred thousand White and Negro fans attended the Monarch games at Association Park the past season without the least bit of friction.” On the field, the Monarchs were winners. They had a winning record in each of their first three seasons. In 1922, the Kansas City Monarchs played a six-game series against the all-white Kansas City Blues of the American Association. After the Monarchs won five of the six games, the American Association Commissioner was so infuriated that he banned interracial play for the league going forward. Later that same season, the Kansas City Monarchs also defeated Babe Ruth’s All-Stars which invoked a similar reaction from Major League Baseball Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis. The Monarchs won a lot of games between 1920 and 1922 but to Wilkinson’s dismay, they were not winning championships. To this point, Foster’s American Giants had dominated the NNL, winning three consecutive titles.

Today, on the site where Municipal Stadium once stood, Monarch Plaza remembers the legendary athletes who played there.

The 1923 season brought significant change to the Monarchs, and the sport as a whole. Wilkinson would hire six black umpires that season; this marked the first instances in professional baseball history of a black umpire calling a game. The team would move to Muehlebach (later Municipal) Stadium. Wilkinson would also send Monarchs’ manager Sam Crawford to manage his All Nations team, which by then was serving as a farm club for the Monarchs. Cuban baseballer Jose Mendez was brought in as a player-manager to replace Crawford. Believed by many to be washed up due to injury, Mendez split his time between playing shortstop and pitching for the Monarchs. During the 1923 season, he posted a 12-4 record as a pitcher. This included a combined no-hitter where he pitched the first five innings.

The ‘23 Monarchs had as good of a roster as could be found in professional baseball. The line-up boasted Oscar “Heavy” Johnson, Walter “Dobie” Moore, and Hurley McNair. The real star of that team, and the entire Negro National League for that matter, was Wilber “Bullet” Rogan.

“[Bullet Rogan was] one of the best, if not the best, pitcher that ever pitched. ”

Rogan was one of the first shutdown pitchers in all of baseball. Known for his sidearm delivery, he had a number of pitches in his repertoire. However, it was his blinding fastball that earned Bullet his nickname. In 1923, his 16 wins and 151 strikeouts led the Negro National League. When Rogan wasn’t pitching, he played the outfield. He was no slouch with a bat. His .364 average, combined with his pitching prowess, led the Kansas City Monarchs to their first Negro National League Championship that season. In 1924, Rogan would notch 18 wins and a .395 average to lead the Monarchs to their second straight league title. Bullet would spend 19 seasons with the Monarchs and even manage the team for nine of those.

The most notable change that came from the 1923 season was the formation of the Eastern Colored League (ECL). After that inaugural season for the ECL, there was a desire from fans of both leagues to have a World Series similar to Major League Baseball. In 1924, the fans got their wish. The 1924 NNL Champion Kansas City Monarchs now had to take one more step if they wanted to be the champions.

Wilber “Bullet” Rogan, also known as “Bullet Joe”, was the predominant pitcher of the early Negro National League. What “Rube” Foster had been during the barnstorming era, Rogan was in the 1920s. PHOTO COURTESY OF: Baseball Hall of Fame

The 1924 Colored World Series pitted the Kansas City Monarchs against the ECL Champion Hilldale Athletic Club of Darby, Pennsylvania. Hilldale was led by future Hallof Famers Judy Johnson, Biz Mackey, and Louis Santop. The ten games of the best of nine series (Game 3 ended in a tie) were played in Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Kansas City with the finale in Chicago. Ignoring the advice of his doctors, Mendez, who was fresh off surgery, named himself the starting pitcher for the clinching Game 10. That decision took Mendez from great to legend. He pitched seven shutout innings and scored a run en route to a 5-0 victory. The Monarchs were champs once again.

The Monarchs would continue their winning ways in 1925, taking home their third consecutive NNL title. They would meet a familiar foe in the Colored World Series. The Hilldale Athletic Club would win five games to one. The Monarchs would continue to post winning records for several years. In fact, the Monarchs would not post a losing season until 1944; the only one in club history. In 1929, the Kansas City Monarchs would once again win the Negro National League title. Since the Eastern Colored League had disbanded after the 1928 season, the Colored World Series was no more. For the third time in the club history, the Kansas City Monarchs were champions.

During the day, the Monarchs stole bases, hit home runs, and won championships. When night fell, their reign in the black community continued. The players would dance and drink the night away at the nightclubs of 18th & Vine. When the clubs closed, the legendary players of baseball would hang out with the legendary players of jazz. They would drink and smoke reefer until daylight, while the musicians partook in the now-famous Kansas City jam sessions. That is, until 1930, when nighttime began to mean baseball too.

In spite of the prosperity of the Pendergast Era, Kansas City was still hit hard by the Great Depression. Having a largely agrarian economy, the city was hit doubly hard by the Dust Bowl. Wilkinson knew that if the Monarchs were going to survive, something would have to change. From 1931-1937, the Monarchs became more of a barnstorming club. In order to maximize the number of games his teams could play, Wilkinson mortgaged everything he owned to secure the $100,000 needed to purchase a portable lighting system of his own design and the generators needed to power them.

“What talkies are to movies, lights will be to baseball.”

Five years before the Cincinnati Reds hosted the Philadelphia Phillies in the “fIrSt EvEr NiGhT gAmE”, the Monarchs were playing under the lights. On August 2, 1930, the Kansas City Monarchs hosted the Homestead Grays of Pittsburgh at Muehlebach Field in the first professional baseball game ever played under the lights. Of note, this game was also the Negro League debut of one of the greatest power hitters in baseball history, Grays’ catcher Josh Gibson. When the Monarchs went on the road, the lights followed on large trailers. When the Monarchs weren’t playing under them, Wilkinson rented his system out to other teams. This maximized the revenue opportunities for the club.

While the Monarchs had found a way to survive the Depression, the Negro National League did not. The NNL folded after the 1931 season. The Monarchs would spend much of the Great Depression barnstorming as an independent team, much like the earliest days of black baseball. During these years, the Monarchs would sign James “Cool Papa” Bell, Willard “Home Run” Brown, Andy Cooper, Hilton Smith, and the most famous player in Kansas City Monarchs history, Leroy “Satchel” Paige.

“I never threw an illegal pitch. The trouble is, once in a while, I toss one that ain’t never been seen by this generation.”

Born in Mobile, Alabama, the exact date of Paige’s birth was up for debate in his lifetime to the extent that his original gravestone bore a question mark in lieu of a birth year. As a child, he worked as a porter at the nearby train station. On one occasion, when hauling bags, someone remarked that the lanky pre-teen looked like a “tree of satchels”. The name stuck. When Paige was 12, he was caught shoplifting. While Paige was serving time at a reform school, he learned to pitch.

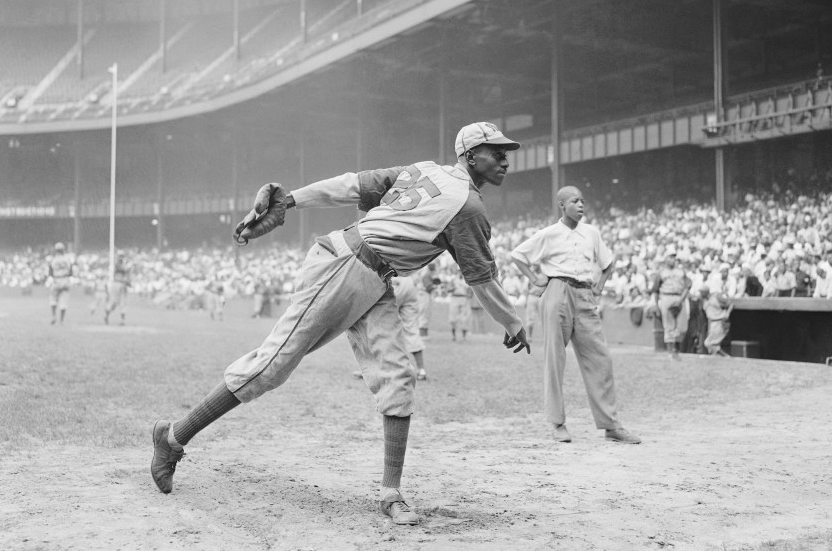

As a pitcher, Paige’s style was unique. His powerful arm intimidated batters. His unique style confused them. It was said that the 6’4” Paige would kick his leg so high into the sky on each pitch that “his foot would block out the sun”. His delivery was deceptive. The right hander would leave his pitching arm limp at his side until rapidly hurling it forward at the precise moment of release. He had a rare combination of speed and control. Paige was also a master of theatricality.

Satchel Paige at Yankee Stadium in 1942 for a game against the New York Cuban Stars. PHOTO CREDIT: Matty Zimmerman / Associated Press

Before there was Muhammad Ali, there was Satchel Paige. Satchel was just as much myth as he was man. He was one of the great self-promoters in sports history. While Paige likely had seven or eight different pitches (twice what the premier starters in the Major Leagues today have!), he made batters believe he had over two dozen. From the “Bee Ball” to the “Little Tom” to the “Midnight Creeper”, they all had names. His antics are legendary. He reportedly would order his entire infield to sit down and then strike out the batter he was facing. His pitching style, dominance, and persona gave Paige unparalleled appeal among fans. He was so popular that by the late 30s, Paige was routinely receiving a third of gate revenues in games he pitched. In 1935, after a decade of pitching for a bevy of black ball clubs, J.L. Wilkinson signed Satchel Paige to a game-by-game contract. In 1939, Satchel Paige became a permanent part of the team.

The 1937 season saw the reestablishment of organized Negro League baseball in the Midwest. The Kansas City Monarchs joined the newly formed Negro American League (NAL). With a roster that included John Jordan “Buck” O’Neil, Smith, Brown, Cooper, and Norman “Turkey” Stearns, the Monarchs would win titles in 1937, 1939, 1940, and 1941. In 1942, when the Monarchs won their fifth NAL title in six years, a familiar challenge awaited.

In 1942, the Negro American League reached an agreement with the second iteration of the Negro National League to reinstitute a Negro League World Series. Once again, the Monarchs were set to play in an inaugural Negro League World Series. Once again, they would face a team from Pennsylvania; the Homestead Grays.

In Game 1 of the 1942 Series, Satchel Paige had a dominant outing giving up only two hits. The Monarchs’ bats came alive in the latter half of the game and defeated the Grays 8-0. In Game 2, Paige forever carved his name in baseball lore.

“Baseball has turned Paige from a second class citizen to a second class immortal.”

In the bottom of the seventh inning, the Monarchs led by two runs. Hilton Smith had pitched five shutout innings, but was relieved by Paige in the sixth. Paige recorded two outs before giving up a triple to the top of the order. Josh Gibson, the most feared hitter in the Negro Leagues, was three batters away. With a runner on third, and two outs, Satchel Paige reportedly did the unthinkable. He intentionally walked the next two batters so that he could face “The Black Babe Ruth” with bases loaded.

As the story goes, Paige taunted his former teammate all the way to the plate, and with every pitch he threw. Paige zipped two called strikes past a frozen Gibson before he caught him swinging for strike three. The Monarchs would go on to win the game. Paige would also make a pitching appearance in each of the next two games as the Monarchs swept the Grays 4-0. The Kansas City Monarchs were World Series Champions once again.

The Kansas City Monarchs hold the distinction of being the only team to appear in, and of course to win, both the Colored World Series and the Negro League World Series. In 1946, first baseman Buck O’Neil was the leading hitter in the Negro American League and led the Monarchs to a second Negro League World Series appearance. The Monarchs would lose to the Newark Eagles four games to three.

1947 was the beginning of the end for the Kansas City Monarchs. Branch Rickey had signed Monarchs’ shortstop Jackie Robinson to the Brooklyn Dodgers’ minor league system in 1945. Robinson broke through baseball’s color line in 1947, becoming the first black player in the Major Leagues in sixty years. A few months later, Bill Veeck signed Eagles’ outfielder Larry Doby to the Cleveland Indians, officially integrating the American League as well. The St. Louis Browns followed suit by signing Kansas City Monarchs’ players Home Run Brown and Hank Thompson. In July of 1947, when Brown and Thompson took the field, it was the first time that two black players appeared on the same team, and the first time two black players played in the same Major League game. Robinson would win Major League Baseball’s first Rookie of the Year award.

Now on display at the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City, Paige’s original gravestone from “Paige Island” in Forest Hills Cemetery gave no birth year for Paige.

Over the next eight years, Major League teams pilfered the ranks of the Kansas City Monarchs. The Monarchs would send more players to the MLB than any other Negro League team.

In 1948, the most popular pitcher in baseball finally got his chance in the “first class” league. The Cleveland Indians signed Satchel Paige, making him the first black pitcher in American League history. At 42, Paige was also the oldest player to make his Major League debut. That same season, Satchel Paige appeared in Game 5 of the World Series for the Indians. Satchel Paige was the first black pitcher in World Series history. Additionally, he and Larry Doby were the first players to win both a Negro League World Series and Major League Baseball’s World Series. In 1971, Satchel became the first Negro League player to be inducted into the Major League Baseball Hall of Fame.

In 1955, the team was sold and moved to Grand Rapids, Michigan. A barnstorming team once again, they would keep the city and moniker, but they were no longer Kansas City’s Monarchs.

Between 1920 and 1955, Kansas City won 12 pennants and 10 championships. The Monarchs put more players in the Hall of Fame, 13, than any other Negro League team. Additionally, the team has four players who are specifically enshrined in Cooperstown as members of the Monarchs. That is more than half the teams in Major League Baseball!

In their time, the Monarchs were so well-regarded, that those who saw them play, considered the New York Yankees to be “the white Monarchs”, not the other way around. They were the longest tenured team in Negro Leagues history and their dynasty lasted for decades. Fielding some of the greatest players to ever play the game, and a pitcher that was larger than life itself, the Monarchs forever changed the game of baseball.

Looking back, many would tell you that Wilkinson and the Monarchs invented nighttime baseball out of economic necessity. I would tell you that it was dictated by fate. I would tell you, that the Kansas City Monarchs were the first to play under the lights because they were the first team worthy of a primetime slot.

So, What Do I Do Now? Visit the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum! Just blocks away from where the Negro National League was formed, the NLBM tells the story of the Kansas City Monarchs and the Negro Leagues. It is one of the best museums in the city and is a must for any Kansas Citian. Located in the same building as the American Jazz Museum, you can purchase a $15 combo ticket to visit both!

In honor of the 100th anniversary of the Negro National League, the Kansas City Streetcar is currently wrapped to honor the Kansas City Monarchs. #22 was, longtime first baseman and manager, Buck O’Neil’s jersey number.

Just A Bit Outside

John Jordan “Buck” O’Neil (1911 - 2006)

It was a bright sunny day in Cooperstown, New York on July 30, 2006. As the result of a special vote earlier that year, a total of 17 players and executives from the Negro Leagues were about to be forever enshrined in Major League Baseball’s (MLB) Hall of Fame. Among those eligible for induction, was Kansas City Monarchs’ first baseman and manager, Buck O’ Neil. He now stood before 11,000 baseball fans after selflessly volunteering to introduce these men and women who were to be inducted. Selfless, because he was not among them. When the votes were tallied months earlier, Buck O’Neil had fallen just short of the Hall of Fame.

“I’ve been a lot of places. I’ve done a lot of things that I really like doing. I hit the homerun. I hit the grand slam homerun. I hit for the cycle. I’ve had a hole in one in golf! I’ve done a lot of things I like doing. I shook hands with President Truman. Yeah. ... But I’d rather be right here, right now, representing these people that helped build the bridge across the chasm of prejudice ... This is quite an honor for me.”

John Jordan “Buck” O’Neil was born in 1911 and raised in Sarasota, Florida. For as long as he could remember, O’Neil loved baseball. Any time there was an opportunity to see Major Leaguers play, the young O’Neil was there. He idolized Ty Cobb. He pored over local newspapers to read Cobb’s box scores. He loved the game, but never conceived that he could play professionally.

A trip to West Palm Beach changed everything. O’Neil’s uncle, who was visiting from New York, took O’Neil to see Rube Foster pitch for the Chicago American Giants against Oscar Charleston and the Indianapolis ABCs. O’Neil was mesmerized. The speed, the athleticism, and the aggressive baserunning were like nothing he had ever seen. More importantly, the American Giants and ABCs looked like O’Neil. He had never seen that before either. From that day on, O’Neil dreamt of playing.

As a teenager, O’Neil moved to Jacksonville to live with relatives so he could attend a high school that accepted black students. He received his diploma and attended college on a baseball and football scholarship. During the summers, O’Neil would barnstorm with the semi-professional Miami Giants. It was while with the Giants, that O’Neil picked up the name “Buck”, after someone confused him with one of the team’s owners, who was named “Buck O’Neal”. In 1934, Buck left college early after being offered $400 a month to play professionally in Havana.

In 1937, Buck O’Neil signed with the Memphis Red Sox of the newly formed Negro American League (NAL). Noted for his large hands, O’Neil’s hand-eye coordination made him a special player. He was a natural defensive first baseman and a pure contact hitter. After a year in Memphis, his contract was acquired by the Kansas City Monarchs.

Buck O’Neil helped the Kansas City Monarchs win the NAL Title in 1939, 1940, and 1941, and the Negro League World Series in 1942. 1942 was also the first time that Buck O’Neil was named to the West Team for the East-West All-Star Game. The annual game at Comiskey Park in Chicago, put the best black players on the field against one another. Since some teams operated independently of leagues, the all-star squads were chosen geographically.

The first black coach in Major League Baseball history, Buck O’Neil (CENTER) was pivotal in the Chicago Cubs signing future Hall of Famers Lou Brock (LEFT) and Ernie Banks (RIGHT).

In 1943, O’Neil made his second appearance in the East-West Game. At the end of the season, he left baseball to serve in the U.S. Navy during World War II. O’Neil would return to the Monarchs in 1946. O’Neil batted .353 that season and picked up his second NAL batting title, having won his first in 1940. The Monarchs would win the NAL that season before losing to the Newark Eagles in the Negro World Series.

As baseball began to integrate, O’Neil was too old, at 36, to have a chance to play in the Majors. In 1948, O’Neil was named the manager of the Kansas City Monarchs. That season, O’Neil scouted and signed Elston Howard. Howard would go on to make 12 All-Star Game appearances and win six World Series as the first black player for the New York Yankees. In the early 1950s, O'Neil found another future star. On the word of former Monarch “Cool Papa” Bell, Buck O’Neil signed a young shortstop named Ernie Banks to the Monarchs.

Under O’Neil’s leadership, the Monarchs continued their winning ways into the 1950s, winning NAL Titles in 1953 and 1955. In 1953, Ernie Banks was named to the East-West Game. After hitting a walk-off, three-run homerun in that game, Banks caught the eye of the Chicago Cubs. With O’Neil’s help, the Cubs signed Ernie Banks as the first black player in club history. Two years later, when the Monarchs moved to Grand Rapids, the Cubs hired Buck O’Neil as a scout.

“I’m in the Hall of Fame because of Buck O’Neil”

During his long tenure as a scout with the Cubs, O’Neil was credited with discovering and signing future Baseball Hall of Famers Ernie Banks (as O’Neil was pivotal to the signing in 1953), Lou Brock, Billy Williams, and Lee Smith. In 1962, Buck O’Neil made history when the Cubs made him the first black coach in the Major Leagues. While a coach, he never once made it on the field during a game, although there was ample opportunity. Somehow, Buck was simultaneously a member of Major League Baseball and, just a bit outside of the League.

Believing that the legends of the Negro Leagues belonged in Baseball’s Hall of Fame, O’Neil refused to campaign for a “Negro Leagues Hall of Fame”. Instead he led the campaign to open the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum at 18th & Vine. O’Neil served as the museum’s honorary chairman until his death in 2006.

O’Neil returned to Kansas City in 1988 to join the Royals as a scout. In 1998, he was named “Midwest Scout of the Year”. O’Neil was a great player, scout, and manager in his own right; but what many remember him for, was being a great ambassador for baseball. In 1990, O’Neil spearheaded efforts to establish the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City, to tell the stories and remember the great players of segregated baseball. In 1994, Buck O’Neil became nationally famous after appearing in Ken Burns’ Baseball. O’Neil used his newfound fame to share the stories of the Negro Leagues and lobby for the leagues’ biggest stars to be enshrined in Cooperstown.

On July 17, 2006, Buck O’Neil would make baseball history once more. He signed a one day contract with the independent Kansas City T-Bones. At the age of 94, Buck O’Neil was intentionally walked, twice, in the Northern League All-Star Game, making him the oldest player to make a plate appearance in a professional baseball game. With the recent rebrand of the T-Bones, O’Neil also has the distinction of being the only person to have played for both iterations of the Kansas City Monarchs.

Two weeks after his historic plate appearance, O’Neil stood in Cooperstown to introduce the seventeen Negro Leaguers who were to be inducted into the Hall; even though he was not among them. According to some reports. O’Neil had fallen a single vote shy of enshrinement. Across the nation, many fans were angry with the Hall of Fame for snubbing O’Neil, but Buck was not among them. He was thankful to have the chance to be considered. He was honored to introduce his contemporaries. He felt loved to have so many fans. If O’Neil was ever angry, upset, or bitter, over being unfairly snubbed, he never once showed it.

In October of 2006, John Jordan “Buck” O’Neil passed away in Kansas City. For his contributions to the game of baseball, President George W. Bush awarded O’Neil the Presidential Medal of Honor a few months after his passing.

After O’Neil’s death, the Baseball Hall of Fame honored him with a statue and a Lifetime Achievement Award named for him. Fittingly, they erected this statue right outside of the Plaque Gallery as if to remind everyone that O’Neil would forever be “just a bit outside” the Hall of Fame.

“If I’m a Hall of Famer for you, that’s alright with me. Just keep loving old Buck. Don’t weep for Buck. No man, be happy, be thankful!”

Buck O’Neil was laid to rest in Forest Hills Cemetery in Kansas City - the same cemetery as his close friend and teammate, Satchel Paige.

The main attraction of Kansas City’s Negro League Baseball Museum is a field, featuring life-size bronze statues of the greatest Negro League player at each positon. Satchel Paige stands tall on the pitcher’s mound. Crouched behind home plate is legendary Homestead Grays’ slugger, Josh Gibson. All ten players on this field are members of the National Baseball Hall of Fame. Just off the field, stands a statue of the manager of this group of legends, Buck O’Neil.

It feels like an apt metaphor for O’Neil’s career. Every bit as deserving of a statue as these legends; so close, but unable to make it on the same field as them.

In 2008, Major League Baseball established the Buck O’Neil Lifetime Achievement Award to honor those who, like Buck, have been stellar ambassadors for the game. The National Baseball Hall of Fame even erected a statue of Buck, and, almost mockingly, placed it just outside the entrance to the Plaque Gallery where Hall of Famers are immortalized. Even in memoriam, O’Neil is so close to being a Hall of Famer, but oh, so far away.

That is the legacy of Buck O’Neil. Just a step away from the Majors, just a vote away from Cooperstown, but in Kansas City, never far at all from our hearts. In spite of what Baseball’s Hall of Fame has to say, Buck O’Neil was a Hall of Fame player. He was a Hall of Fame scout, Hall of Fame coach, Hall of Fame manager, and Hall of Fame ambassador for the game. Most importantly, John Jordan “Buck” O’Neil was a Hall of Fame human being. Thank goodness, Cooperstown does not get to weigh in on that.

So, What Do I Do Now? Pay your respects to Buck O’Neil at Forest Hill & Cavalry Cemetery, where a beautiful monument marks his grave. The legendary Satchel Paige has his own memorial at his grave a few hundred feet away! Also, pay a visit to the John “Buck” O’Neil Center, formerly the Paseo YMCA. The Negro National League was formed in this very building. The adjacent field and exterior murals honor some of the greatest players to ever wear the Monarchs uniform.

When Jackie Robinson was signed by the Brooklyn Dodgers, it was a huge victory for equality but it was also the beginning of the end for the Negro Leagues.

When people talk about Kansas City 2000 years from now, they’ll remember three things: barbeque, baseball, and jazz. All three grew up within a stone’s throw of 18th & Vine. In hindsight, it seems fitting that Jackie Robinson was signed by Brooklyn. Harlem had taken away Jay McShann and Charlie Parker, effectively ending Kansas City’s Jazz Age. Now the Dodgers had opened up the Monarchs as a farm team for the Majors. And Dodgers owner Branch Rickey didn’t even have the decency to purchase Robinson’s contract. The splendor of 18th & Vine was quickly fading, and Gotham was the harbinger of death.

In the decade that followed Robinson’s Dodgers debut, many other Negro Leaguers made their way to the MLB; until the Negro Leagues were a shadow of what they once were. While the integration of baseball represented a major victory in the fight for equality, it was a double-edged sword. This milestone moment led to the demise of the Negro Leagues. This was detrimental to many black communities across the nation. Kansas City’s was among the hardest hit.

“You’ll never know what [Don Newcombe] and Jackie [Robinson] and Roy [Campanella] did to make it possible to do my job.”

At their height, the Negro Leagues, and their respective teams, were some of the largest, and most lucrative, black-owned businesses in America. Not only were they black-owned businesses, but they spent their profits in the black community. Similar to the nightclubs where jazz was innovated, professional baseball was a financial boon for the neighborhoods surrounding 18th & Vine. The traveling teams stayed in black-owned hotels. Players for the home and away side ate at black-owned restaurants and danced at black-owned clubs. Jazz and baseball players alike, paid rent to black landlords and bought their essentials from black-owned stores.

They had no other choice. In spite of being some of the most popular athletes and musicians of the time, and their popularity spanning all races, society regarded them as lesser. Satchel Paige, Count Basie, Bullet Rogan, Buck O’Neil, Bennie Moten, and Charlie “Bird” Parker are legends in our day, but were treated as inferior in their own. Even in 1971, when Paige became the first person inducted into Baseball’s Hall of Fame based off his Negro League career, the Hall attempted to create a gallery separate from where Major Leaguers were honored. The Sandlot taught us that “legends never die” but history teaches us that even immortals can be treated as second class.

In Kansas City, the conviction of Boss Tom Pendergast, and the subsequent crackdown on nightclubs that ended the Jazz Age, was the beginning of the end for many burgeoning black communities on the Eastside. While the integration of baseball is a moment to be celebrated, it was also 18th & Vine’s death knell.

The final curtain call for the Monarchs, and the community who supported them, came in 1955. Major League Baseball had arrived on the Eastside but Major League dollars did not follow. The relocation of the Philadelphia Athletics created stadium scheduling difficulties. This led to the sale of the Monarchs and their move to Grand Rapids.

While Municipal Stadium still had a professional baseball club, the Eastside no longer had a team. And with 18th & Vine now quiet, this city no longer had its soul.

Join me next week, as we finish our exploration of Kansas City’s history through the stories of influential black men, women, and entities. Subscribe at the bottom of disKCovery’s home page to be the first to know when Chapter V drops.

Have a favorite story? Have one you want to hear? Let me hear it in the comments!

Many thanks to my mother, Janell Dignan, for proofreading and editing these stories. I could not have done this without you!