Herstory of the City, Part V

While it’s snowy now, in the spring and summer, the Women’s Leadership Fountain, Kansas City’s oldest surviving fountain, is a sight to behold.

Published March 30, 2022

A NOTE FROM THE WRITER: When I started disKCovery, it was not only about sharing my own journey to discovering Kansas City, but a way to push myself to continue being a tourist in this city that I am proud to call home. While that journey is largely about the Kansas City we know now, it can be difficult to understand and truly love a city without understanding the context of what we see today. So for this month, Women’s History Month, I stepped away from my usual programming to share a series of essays that explore some of the kick-ass ladies who helped shape our city, our region, and the world. This article represents the conclusion of that five-part series. If you have not already done so, I encourage you to click HERE and begin with “Herstory of the City, Part I”.

There are a few reasons that writers write. As for me, this month, I have shared the stories of some incredible Kansas City women. Whether or not you are entertained, persuaded, or informed; well my friend, that is up to you.

Part 5: Who Run The World? Girls.

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness”

When the colonies that would become the United States first declared their intent to form their own nation to the British crown, they argued they were justified to do so because their God-given right of equality, had not been realized. Our Founding Fathers asserted that the failures of the British Government to do so, gave them a right to self-determination. More than any, the above ideal of this statement of secession, that “all men are created equal”, became a rallying cry as the colonies galvanized against Great Britain. In the aftermath of the United States gaining independence, it was still a pervasive ideal but ironically, the United States was guilty of the very thing they had accused King George III of. The United States failed to realized the promise of their own Declaration of Independence and ensure all of their people a right to life and liberty.

In 1979, suffragette Susan B. Anthony, who spent time in Leavenworth, Kansas, became the first woman to ever appear on U.S. money.

It was 80 years after the United States gained independence at Yorktown, that another war would break out over this promise. This time the American Civil War was fought between the states in order to extend the Declaration’s greatest promise to all men, regardless of their skin color. After a Union victory, three amendments to the United States Constitution (the 13th, 14th, and 15th) were ratified in order to extend equal protection under the law to all emancipated slaves and African Americans. While the United States still failed to treat all people equal under the law, the passage of these three amendments opened the door to equality for all. By extending the power to the federal government to ensure equality when states failed to keep this promise, these three amendments set the tone for the century to come.

Here in the US, the 20th century was one marked by the struggle for equality by a number of marginalized classes. The battle to realize equality for all had waged for as long we have been a nation. Abolitionists spent decades making their voices heard before a literal war was waged over the issue. As the tensions that led to the Civil War mounted, another equality movement had its beginnings. In 1848, the Seneca Falls Convention took place. It was a gathering to lobby for women’s rights that was headlined by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott. Schoolteacher Susan B. Anthony, who spent significant time in Leavenworth, was an abolitionist and conductor on the Underground Railroad. In the wake of the Civil War, after meeting Stanton, she became a fierce advocate for women’s suffrage (the right to vote). While Anthony would never live to see this aspect of the Declaration’s promise realized, she is remembered more than anyone else, for championing this cause. She was even arrested multiple times for attempting to vote illegally in protest. In 1979, these efforts were recognized when Anthony became the first woman to appear on U.S. money.

While these amendment had freed black Americans from the bondage of slavery, the promise of equality still went unkept. “Separate but equal” was the law of the land but by its very nature, separate is always unequal. So as the calendar turned to the 1900s, the stage had been set for the United States to take another monumental step towards ensuring that all men and all women were equal. Like Susan B. Anthony before them, that fight for equal rights in the 20th century, was led by Kansas City women.

Kansas City’s Mother

Phoebe Jane Ess (1850 - 1934)

If you ever do find yourself at 9th and The Paseo to enjoy simple beauty of the Women’s Leadership Fountain, you may find that among the very first names honored is that of Phoebe Jane Ess. While you likely have not heard her name until now, there are few people who did more to serve the people of this city than Ess. An advocate for municipal reforms that improved the quality of life for many in KC, The Kansas City Star once said, “... if cities may be endowed with mothers, [Phoebe Jane Ess] rightly would be called the mother of Kansas City.” Having earned the mantle of Kansas City’s symbolic mother, who exactly was Phoebe Jane Ess?

“I was born with the principles of equal opportunity for all ingrained in my soul.”

She was born Phoebe Jane Routt on March 3, 1850 in Versailles, Kentucky. When Phoebe and her twin sister Betty were four years old, their parents moved the family to Liberty, Missouri seeking a better life. Phoebe and Betty were both students at Clay County Seminary. Phoebe graduated in 1865. In 1872, Phoebe moved to Kansas City, Missouri to take a teaching job at Washington School. Washington School was the first-ever public school in Kansas City and located in the present-day Columbus Park neighborhood. In 1875, Phoebe married Henry Newton Ess, a partner at the distinguished law firm of Karnes & Ess.

Phoebe Jane Ess helped establish over 30 different clubs in Kansas City and was the leader in the fight for equality for a number of marginalized classes. PHOTO COURTESY OF - Kansas Historical Society

As many women did in that era after they got married, Ess left the teaching profession. However, she directed her energies elsewhere as she did not lose interest in helping others. She was a strong advocate for women’s suffrage, education reform, prison reform, the establishment of libraries, children’s rights, elders’ rights, aiding the impoverished, and the Temperance Movement. As such, she began to get involved in a number of women’s clubs.

Her involvement with clubs began in 1882. She was a charter member of the Tuesday Morning Study Club, which was dedicated to improving and expanding upon educational opportunities for women. Primarily, it was an opportunity for the female members to get better educated. Ess saw the potential for women’s clubs but believed they should not only be a tool for self-improvement but societal improvement as well.

Ess was instrumental in the formation of the General Federation of Women’s Clubs (GFWC), Susan B. Anthony Civic Club, Missouri Federation of Women’s Clubs, Equal Suffrage Association, League of Women Voters, and the Athenaeum, which became the most influential women’s club in the city. It is believed that Ess was involved in the formation of over 30 women’s clubs and social improvement organizations. Ess is remembered as “dean of Missouri club women” due to her involvement in all these clubs, and the fact that she presided over many of them at one time or another.

Phoebe Jane Ess is most notable for her passion for women’s suffrage. In the early part of the 20th century, Ess traveled all over Missouri garnering support for an amendment to the United States Constitution that would grant women the right to vote. In 1912, Kansas recognized the right of women to vote. Jackson County was one of Missouri’s first counties to similarly recognize the right to vote for women. Ess, and the clubs she helped found, are largely credited with this progress.

Beyond the issue of women’s suffrage, Phoebe Jane Ess believed in educational reform and successfully lobbied the Kansas City Public School District in order to get fine arts programs and playgrounds for every school. She established the Phoebe Ess Scholarship Loan Fund which assisted over 400 girls in pursuing an education. In 1918, even though women could not yet vote, Ess became the first woman in Kansas City history to run for public office when she ran for the Kansas City School Board. While she lost that election, it did not deter her efforts to make Kansas City a better place to live. A proponent for World Peace, she also canvassed promoting disarmament. She actually collected more petition signatures for disarmament than any person in the United States.

In 1934, Phoebe Jane Ess passed away in her twin sister Betty’s home. Her husband, Henry Ess, had passed away 17 years prior. The legacy of Phoebe Jane Ess was a lifetime of service in this city that has been rarely matched, and never exceeded. After her death, The Kansas City Star said of Ess, “To have followed her active trail through the years would have been to have seen the steady unfolding of women’s suffrage and rights, the blossoming of countless charities, and the constant amelioration of humanity everywhere through her crusades against vice and injustice.” During the 62 years she called Kansas City home, Phoebe Jane Ess was a great humanitarian and an unrelenting adversary of inequality. At her eulogy it was said that, “Honesty, courage, sincerity, justice, liberty - these were the foundation stones upon which she built her great, vital, far-reaching life.” What more could a city ask for in a mother?

So, What Do I Do Now? Visit Kansas City’s oldest surviving fountain! Along with the Berry Sisters, Nell Donnelly Reed, and Nelle Peters, Phoebe Jane Ess is one of thirteen women whose name is inscribed at the fountain. You can also pay your respects to Phoebe Jane Ess at Elmwood Cemetery where she is buried.

Kansas City’s Orator

Ida Bowman Becks (1880 - 1953)

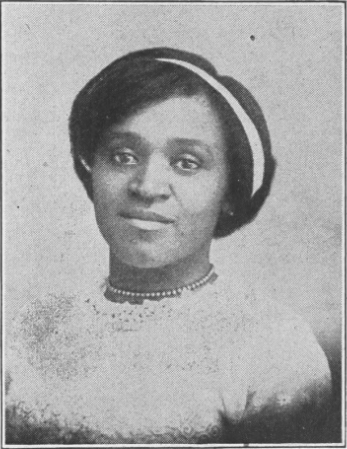

Around the same time that Phoebe Jane Ess was fighting for gender, age, and economic equality in Kansas City, Ida Bowman Becks was engaged in a similar battle. Like Ess, Ida Bowman Becks was a lecturer, clubwoman, and a suffragette. As a black woman, Ida Bowman Becks would also become one of Missouri’s greatest patrons for Civil Rights as well.

Ida Bowman Becks was renowned for her public speaking ability and her unmatched debate skills. PHOTOGRAPHER - Unknown

Ida Bowman was born on March 28, 1880 in Armstrong, Missouri. When Ida was sixteen years old, she enrolled at what is now Lincoln College Preparatory Academy in Kansas City, Missouri. After graduating as class valedictorian in 1899, she attended the Chicago School of Elocution. It was here that she first received training and instruction in public speaking. To finance her education, she worked in a private residence where she earned one dollar per week. As a student, she took a number of public speaking engagements at schools and civic events. As a result, she quickly earned a reputation as a talented and effective orator.

After a few years in Chicago, Ida Bowman moved to Dayton, Ohio where she worked as a secretary for the local chapter of the Colored Women’s League (CWL). The CWL was a national organization dedicated to improving conditions and creating opportunities for black women, children, and the poor. It was here that Ida Bowman first began to see the potential and possibilities that existed for black women. It was also in Dayton that she met H.W. Becks who she wed in 1907.

In 1908, H.W. and Ida Bowman Becks moved to Kansas City, Kansas. Ida took a job working for the Florence Crittenton Home in Topeka, an institution that provided assistance for unwed pregnant women and hoped to reform prostitutes. Given the religious affiliation of the organization, some of their practices were not without controversy. After two years, she became a field representative for a private elementary school based in Washington, D.C.

In Dayton, Becks had first dedicated herself to the plight of African-Americans and women alike. Even before the concept had a name, it could be said that Becks was one of the earliest activists to adopt a strategy around intersectionality. Intersectionality is a framework which explores how different aspects of a person’s social identity overlap in order to identify areas of advantage or disadvantage. As a black woman, Becks clearly recognized herself as a member of two marginalized classes of people and sought to improve conditions for both of her communities.

While living in the greater Kansas City area, Becks became involved in a number of women’s clubs and local charities. She began to speak at club meetings, public events, and local churches in favor of women’s suffrage. She was also a leader in the local black community. She traveled around the metro, and throughout Missouri and Kansas, speaking on and engaging in debates over civil rights and women’s rights. As had been the case in Chicago, Ida Bowman Becks became renowned for her eloquence, and was also known as a very capable and fierce debater. She was also a published writer and playwright.

“[Ida Bowman Becks’] manner of address is direct, dramatic, and at times sensational, yet pleasing and intensely interesting. She is a fearless advocate for women’s suffrage and is an uncompromising defender of the Afro-American race.”

After women gained the vote, she continued to fight for racial equality and got involved in the fight for healthcare equality. Becks helped to establish the Yates Youth Women’s Christian Association (YWCA) and the Kansas City Urban League. She was involved in fundraising efforts for the American Red Cross and served on the board for the Wheatley-Provident Hospital, Kansas City’s preeminent black hospital. She represented Kansas City as a delegate to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the National Negro Congress. She was also the chair for the local chapter of the Negro Women’s National Republican League.

From a young age, Ida Bowman Becks was a talented lecturer credited with advancing the cause of women’s and civil rights in Kansas City and the surrounding area. A champion for women and African-Americans, Becks continued her activism late into her life. She and her husband, H.W., were also involved in the Baptist church until she passed in 1953. At a time when women, blacks, and the poor cried out for a voice, Kansas City’s most powerful orator, Ida Bowman Becks, gave them one.

So, What Do I Do Now? It is mind-boggling to me that Ida Bowman Becks is not among the women who are included on the Women’s Leadership Fountain. You could pay a visit to Wheatley-Provident Hospital, as Becks was on the board and passionate about healthcare equality. Additionally, you can learn more about Ida Bowman Becks and her advocacy by visiting the Black Archives of Mid-America.

Marches like this one were fairly commonplace in the early 1900s as women, and allies, fought for the right to vote. PHOTO SOURCE - Unknown

Kansas City’s Advocate

Esther Swirk Brown (1917 - 1970)

So far, the two women that have been explored in this chapter were both heavy proponents for educational reforms. Becks especially counted racial equality among the causes for which she tirelessly campaigned. Public schools and universities were one of the earliest battlegrounds for the Civil Rights Movement, and specifically, schools in Missouri and Kansas. As the push for racial equality gained traction and turned its full attention on educational opportunities for black students, an unlikely champion arose in Merriam, Kansas.

Esther Swirk Brown was the daughter of Russian-Jewish immigrants who fought for racial equality in Kansas. PHOTO COURTESY OF - Kansas Historical Society

Esther Swirk was born to Russian-Jewish immigrants in Kansas City, Missouri in 1917. Her father Ben was a watchmaker who owned Swirk Jewelers. Her mother, Jennifer, was taken by cancer when Esther was ten years old. As a student at Paseo High School, Esther was always socially conscious and even picketed for the rights of garment workers.

During the 1920s, when Esther was growing up along The Paseo, real estate developers, such as J.C. Nichols, were actively redlining Kansas City’s most historic neighborhoods. Redlining is the deliberate practice of restricting purchase loans to people based on demographic factors, in order to funnel those members of a community into specific neighborhoods. As Kansas City developers built new, modern, gleaming neighborhoods and expanded the footprint of the city, local financial institutions made it easy for white, Protestant families to secure loans and move into these new developments. These same neighborhoods were the ones that began to receive public funding and other amenities. Meanwhile, “outdated” parts of the city were earmarked for potential homeowners who were African-American, Jewish, and Catholic (and Latin-American as a result). The only way members of these groups could hope to own a home was to move into these neighborhoods. Thus, Troost Avenue became a physical dividing line in Kansas City. The impacts of this systemic segregation are still felt and seen in Kansas City today. Understanding that history and where Esther Swirk grew up, it may explain why she was so empathetic to the causes of the marginalized groups.

After Esther graduated from Paseo High, she attended the University of Chicago and Northwestern University. Upon completion of her college education, she moved back to the Kansas City area. In 1943, she married Paul Brown, a US Air Force officer, and the couple had two daughters. After the conclusion of World War II, the family moved to Merriam, Kansas. She became active in a number of Jewish organizations, and her synagogue, but given her upbringing, Esther Swirk Brown realized that discrimination extended beyond her own circles and often engaged with other communities. In 1947, while living in Merriam, the Kansas housewife who had once picketed for the rights of garment workers, found a new cause.

That year, a local school board passed a bond measure for $90,000.00 to build a new state-of-the-art elementary school for white children in the nearby South Park township. At the same time, black children in that area were expected to continue to attend Walker Elementary, a one-room school that had been built nearly 60 years prior. It had outdoor plumbing, lacked proper heating, and had dirt floors. Aside from the physical make-up of the building, Walker Elementary had incredibly outdated class materials, severely limited resources, and only had two full-time teachers to instruct eight different grades. Additionally, the new district was gerrymandered in such a wanton fashion, that many black children had to walk right by the new South Park Grade School in order to attend their inferior school. The parents of the children had to pay taxes that funded the new South Park school even though their children could not attend. This was the case for Helen Swan, Esther Swirk Brown’s housekeeper, and her children.

When Brown became aware of the conditions at Walker Elementary, and the longer walk, she immediately recognized it as a violation of the Plessy v. Ferguson decision of 1896. Under this Supreme Court ruling, it had been determined that segregation was permissible as long as “separate but equal” facilities were provided for both black and white patrons. Brown realized that when it came to education in Kansas, the schools were separate but they were far from equal. She also realized that, black parents like Helen Swan, struggled to capture the attention of school officials in the district over this gross mistreatment. Upon seeing the conditions in Walker Elementary firsthand, Esther Swirk Brown felt an obligation to take action and stand up for the black community.

The first thing she did was help to organize a local chapter of the NAACP in the South Park community. She then persuaded that chapter to sue the school district on the grounds that they were in violation of Plessy v. Ferguson. Since the school district was unwilling to provide an equivalent option for black students, Brown contended that South Park Grade School should be integrated. To try their case, Brown enlisted the help of attorney Elisha Scott, Sr., who had a reputation for winning supposedly unwinnable cases. Scott famously negotiated the first constitution for the Negro National League in Kansas City in 1920, had secured the charter for the first nationally chartered African-American bank (in Boley, Oklahoma), and provided assistance for black families in the wake of the Tulsa Race Massacres of 1921. Brown persuaded Alfonso Webb, one of the Walker Elementary students’ fathers, to list his son as the lead plaintiff in the case. She also began fundraising to cover the legal costs for the lawsuit.

In 1948, Brown organized a boycott of Walker Elementary due to the unjust conditions. She opened her home to the students. She helped teach them, and also fundraised within the organizations she was a member of, to cover the salaries of the two teachers so they could teach at the Browns’ home school. Around that time, a lower court agreed with Brown and the NAACP; School District No. 90 had failed to provide equal educational accommodations for black students.

Esther Swirk Brown’s involvement in the case of Webb v. School District No. 90 came at great personal cost to her and her family. Over the course of those two years, she was often a target of obscene insults and gestures, racial slurs, harassing phone calls, and in some cases, assault. Her family home was a target for vandalism and on one occasion, a cross was burned in the Browns’ front yard. She even faced discrimination from her own family. In 1949, Paul Brown was working for Ben Swirk when he denounced his own daughter as a communist and fired Paul. Paul was also asked to resign from the US Air Force Reserves as a result of Esther’s activism. The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) even orchestrated a smear campaign against her. Amazingly, Esther Swirk Brown soldiered on.

That same year, in the summer of 1949, the Kansas Supreme Court similarly ruled in favor of Esther Swirk Brown and the NAACP. It was determined that until such time that School District No. 90 could provide black children with a school that was equivalent in quality to South Park Grade School, the all-white school would have to admit any black children who wished to attend. When South Park’s doors opened to black and white students alike that fall, every black student showed up for the first day in a brand new shirt or a brand new dress, thanks to the generosity of Esther Swirk Brown and her network of donors.

“We conclude that in the field of public education, the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.”

Esther Swirk Brown continued to push for the integration of public schools and was a strong ally of African-American communities in Kansas. Brown has been credited with shifting the NAACP’s focus from integrating colleges and universities to integrating elementary schools. In Topeka, Esther Swirk Brown was pivotal in convincing Oliver Brown (no relation) to name his daughter Linda as the lead plaintiff in a similar case. For this case, the NAACP enlisted one of the attorneys from Webb v. School District No. 90, Thurgood Marshall, who would later go on to become the first African-American Supreme Court Justice. Of course, this was the famed case of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka which would make it all the way to the United States Supreme Court. In 1954, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of Linda Brown which led to the desegregation of public schools nationwide.

Esther Swirk Brown remained a crusader for civil rights until her death from cancer in 1970. One scholar once surmised that Brown “saw herself as just a Kansas housewife who was indignant about injustice.” Luckily for the people of Kansas, and later the nation, this housewife not only recognized injustice but had such a sense of duty and an incredible capacity for empathy that she became exactly the champion that black Kansas Citians needed at a time when they needed her the most.

So, What Do I Do Now? Similar to Phoebe Jane Ess, Esther Swirk Brown is one of thirteen women whose name is inscribed on the Women’s Leadership Fountain at 9th & Paseo. Pay a visit to Brown Memorial Park! Located at 5040 Booker Street in Merriam, this park named for her does have a historical marker that recognizes Brown’s contributions to the fight for equality.

In 1947, the opening of the state-of-the-art South Park School created an obvious disparity between the educational opportunities available for white children and black children. This prompted Esther Swirk Brown, and others, to act. PHOTO COURTESY OF - Johnson County Museum

When the 19th amendment was ratified in 1920, granting women the right to vote nationwide, it was a major victory in the goal to realize the initial promise this nation made to its people. When the decision came down in Brown vs. Board and paved the way for integration of all institutions, it similarly moved us closer to meeting the challenge of that hallowed creed. Regardless of political affiliation, when Kamala Harris became the first woman and the first person of color to be Vice-President of the United States just last year, this was similarly another victory towards that goal. We hold these truths to be self-evident that all men and women are created equal! The push for women’s suffrage and the Civil Rights movement were the precursor for every single movement of the 20th and 21st centuries. As even today, we are still engaged in a struggle for all people to truly be equal under the law, as our Founding Fathers promised. Many of these early victories were won thanks to amazing women here in Kansas City, and Ess, Becks, and Brown are far from alone! You may recall that last February, I wrote about Lucille Bluford, the longtime editor of The Kansas City Call. Not only did The Call cover, and effectively preserve, the stories of black neighborhoods and civil rights demonstrations, Lucille Bluford’s editorials spurred Kansas Citians to take action in the Civil Rights Movement.

Picking up the mantle of these champions was Kansas City’s most famous activist of the 20th century, Florynce Kennedy. Born in Kansas City, and a valedictorian at Liberty High School, Kennedy moved to Harlem. There, she attended Columbia University where she received her degree in pre-law. When Columbia’s law school barred her entrance due to her race and gender, Kennedy threatened to sue the school. When they admitted Kennedy, she was one of eight women, and the only black person, in her class. Kennedy would continue that fight once she became a lawyer. She became a bit of an icon in the Civil Rights and feminist movements in the 1950s and 60s. She was a proponent for intersectionality and believed that by bringing together women, African-Americans, and other groups that faced systemic discrimination, she could form alliances that would lead to change for all. She often drew ire for her antics, and even her signature look of a cowboy hat and pink sunglasses, but Kennedy was a passionate woman who was willing to do whatever it took to bring attention to the issues. Her most famous of these antics was organizing the Harvard Pee-In in 1973, in which female students poured jars of fake urine down the steps of Lowell Lecture Hall at Harvard University to protest the university’s lack of women’s restrooms. The Kansas City-born Kennedy is remembered for her work in Civil Rights, women’s rights, and reproductive rights.

In the same way that Kennedy was the first woman, and person of color, admitted into Columbia Law School, a number of barrier-breaking women have come from Kansas City. While the military did not permit female soldiers until 1948, Leavenworth’s own Cathay Williams enlisted in 1866. To this day, she is the only woman known to have served with the Buffalo Soldiers and is believed to have been the only black female U.S. soldier of the 1800s.

Eliza “Lyda” Conley was a Kansas City, Kansas native and a member of the Wyandot tribe. As an attorney, she actively campaigned to prevent the development of the Huron Cemetery. When her fight made it all the way to the nation’s highest court in 1907, Lyda became the first Native American woman to argue a case before the United States Supreme Court. Her victory led to the establishment of the Wyandot National Burying Ground in KCK.

Kansas City, Missouri’s own Dorothy Vaughan was a mathematician and human computer who went to work for the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA - the precursor to NASA). As the supervisor for the West Area Computers, she was the first African-American woman in the history of NASA to supervise a group of staff. Most famously, Vaughan taught herself, and the African-American computers she supervised, the programming language Fortran to ensure the jobs of her entire staff when computer machines inevitably replaced their human equivalents. Vaughan is one of three women whose story was told in the 2016 Disney film Hidden Figures (portrayed by Octavia Spencer).

“Women must try to do things as men have tried. When they fail, their failure must be a challenge to others.”

Recently, Lynette Woodard served as the head basketball coach at Winthrop University. A four-time All-American for the University of Kansas, the Kansas born Woodard was the first female basketball player to have her number retired by the Jayhawks. She helped lead the United States to a gold medal in women’s basketball in 1984. In 1985, Woodard made history as the first woman to play for the Harlem Globetrotters. In the early 90s, she served as the Athletic Director for the Kansas City, Missouri School District. And then from 1997 - 1999, Woodard finished out her playing days by being an inaugural player in the Women’s National Basketball Association (WNBA). In 2004, Woodard was elected to the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame.

And while it’s not technically part of the Kansas City metro area, I would be remiss if I failed to mention the Queen of the Skies, Atchison, Kansas’ own Amelia Earhart. A pioneer in aviation, Amelia Earhart is mostly remembered for the number of aviation records she set. She was the first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean. She was a proponent for the expansion of commercial air travel. However, outside of aviation, she was outspoken in the fight for equal rights for women. Earhart mysteriously disappeared in an attempt to become the first woman to circumnavigate the globe via airplane. However, the letter she left behind for her husband is a reminder of why she was doing what she did. “Please know I am quite aware of the hazards. I want to do it because I want to do it. Women must try to do things as men have tried. When they fail, their failure must be a challenge to others.”

Thanks to the efforts of such women, a new generation of women, and minority groups, walk across floors littered with glass shattered by previous generations. While there are still heights to reach and rights to realize, Ida Bowman Becks, Esther Swirk Brown, Phoebe Jane Ess, and a host of Kansas City’s most badass ladies, took their mallets to some of history’s most obnoxious glass ceilings and created a world where all people can truly pursue happiness.

Today, a placard at Brown Park in Merriam, Kansas remembers the contributions of Esther Swirk Brown. PHOTO CREDIT - Deborah Keating, UMKC

“Frank Harte once quipped that, ‘Those in power write the history while those who suffer write the songs.’ But what happens when history is made by the ones who also suffered? What happens when the contributions of the songwriters are lost?”

It has often been said that a picture is worth a thousand words, so why, in terms of our own history, do we make the mistake of limiting ourselves to 490? We build monuments to and name our streets and parks for great men, while the great women of history are relegated to a footnote. What happens when history was made by those who also suffered? Their contributions become a fleeting song; and if we’re not careful, that song is buried beneath the weight of history and tradition.

Yet, when we do know the lyrics, and we know where to look, that melody grows louder. That song is no longer so faint. Soon a drive through Kansas City becomes a catchy refrain.

I drive through the River Market and I think about how Kansas City became “The Paris of the Plains”. I think about how this neighborhood was once filled with brothels and gambling dens. I hear the piano in the lounge of Annie Chambers’ resort and think about everything she did to help women in the most untraditional of ways. I look across the Missouri River to the Charles Wheeler Downtown Airport and I can’t help but think about Amelia Earhart. I think about TWA and the airline’s owner who created the aviation feature Hell’s Angels. In that moment, I hear the signature laugh of Kansas City’s Platinum Blonde, Jean Harlow.

I cross the highway into the Garment District and remember that the world’s largest dressmaker, Nell Donnelly Reed, made this area what it once was. I drive by the Library District and think of Carrie Westlake Whitney. I see that giant bookshelf and I just hear, well, silence, and the soft shuffle of turning pages. They combine with the whir of Nelly Don’s sewing machines. They add the percussion, and the song begins to take shape.

I pass the College Basketball Experience and immediately think of Lynette Woodard, the first woman to ever play for the Globetrotters. I drive past Film Row and remember Ginger Rogers, Joan Crawford, and Hattie McDaniel. I think of the glitz and glam of Hollywood’s Golden Age. I pass Union Station and immediately remember the first time I went there to visit Science City. I think about Dorothy Vaughan and how she helped to pave the way for a number of young girls to pursue careers in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics).

Continuing south, I go by Hospital Hill and am overwhelmed by the legacy of the Berry Sisters and everything they gave, and continue to give this city. This city’s song continues to build. Soon enough, I find myself at the Country Club Plaza, face to face with Nelle Peters’ Magnum Opus, the literary block.

“What happens when the names of history-making women are buried under the accomplishments of men who wrote the story? ”

And then as I head back north towards my home, I hop on to Kansas City’s oldest boulevard, The Paseo. I think about the dividing line that Troost and Paseo long represented. I think about Esther Swirk Brown and her fight to integrate schools. I can almost hear the powerful oration of Ida Bowman Becks as she campaigns for equality.

Suddenly, intrusively, I hear a riff! It clashes, but it merges with the song to create something beautiful, and powerful, and new. It is the most Kansas City of sounds - the sound of improvisation. I hear the women of Kansas City jazz as I drive right past 18th & Vine. I hear Mary Lou Williams belting out her own contribution to Kansas City’s song. I hear the staticy feedback of an old-time radio. Another mile still and I hear the splashing of Kansas City’s oldest fountain. I think about Phoebe Jane Ess, the mother of Kansas City, and her fight to create educational and voting opportunities for women. I think about the other 12 incredible ladies who are remembered with that basin, and the symphony overpowers me.

The notes take shape and form themselves into bars of music we can easily hum. But then, as I drive through this city, I realize I no longer have to hum. While my knowledge of the song is far from complete, I find that I know several verses! Now I have the power to sing along!

What happens when we forget the lyrics? What happens when the names of history-making women are buried under the accomplishments of men who wrote the story? What happens when the song is too faint to hear? What happens, is we make it a point to learn the lyrics. We take a deep breath, we close our eyes, and listen for their song. We ensure that it lives on.

History gives us the names of men that it demand we remember and overshadows the incredible women that it demand we forget. But like these incredible women, herstory has a strength that is largely underestimated and overlooked. That dignified strength has allowed herstory to survive.

History has given us the names of men to remember and has asked us to forget the names of the women who have contributed their own verses to our story. Nevertheless, their song persists.

While largely lost, that song is not forgotten. It is true that for many, myself included, the melody has laid dormant. This journey has helped me, and hopefully you, to learn a few of the lyrics. Hopefully, knowing a part of the song, makes us want to seek out even more verses. And if enough of us take the time to hum that tune and point out the notes across our city, then maybe, just maybe, the stories of these women can find new life.

What happens when history is made by those who also wrote the songs? We pick up the mantle and sing along.

Maybe, as we learn the lyrics, we will find the 510 words that are missing. Maybe we can be the ones to complete the picture.

And then maybe, just maybe, when the story of Kansas City is told, we will remember to sing their song.

Well, that’s all she wrote. For those who chose to join me on this journey through herstory - THANK YOU!

Who was your favorite Kansas City icon to learn about this month? As always, let me hear it in the comments.

Many thanks to my mother, Janell Dignan, for proofreading and editing these stories. I would not have pulled off this series without you!