Herstory of the City, Part IV

Located in the heart of the Crossroads Arts District, Kansas City actually has the largest intact Film Row in the nation.

Published March 24, 2022

A NOTE FROM THE WRITER: When I started disKCovery, it was not only about sharing my own journey to discovering Kansas City, but a way to push myself to continue being a tourist in this city that I am proud to call home. While that journey is largely about the Kansas City we know now, it can be difficult to understand and truly love a city without understanding the context of what we see today. So for this month, Women’s History Month, I am going to step away from my usual programming and share a series of essays that explore some of the kick-ass ladies who helped shape our city, our region, and the world. If you have not already done so, I encourage you to click HERE and begin with “Herstory of the City, Part I”.

There are a few reasons that writers write. As for me, this month, I am going to share the stories of some incredible Kansas City women. Whether or not you are entertained, persuaded, or informed; well my friend, that is up to you.

Part 4: Superstar

For many Kansas Citians, the Crossroads Arts District is a favorite destination. People from all around the Metro flock to the Crossroads to try local beers in Brewers’ Alley, grab a bite to eat from food trucks and an eclectic collection of restaurants, and, as the district’s name implies, to enjoy the art. Housed within this downtown district are a number of small studios and art galleries. On full display throughout the Crossroads are a diverse array of murals painted on the old brick by Kansas City artists. The district is especially notable for the showcases of local artists that transpire there on the First Friday of every month. While today, we most associate the Crossroads Arts District with paintings and murals, it was originally a bustling district centered around a very different artform - motion pictures.

In 1910, In Old California was the first movie to be filmed entirely in Hollywood. By 1915, all of the major studios had relocated their primary studios to southern California and by the mid-1920s, the motion picture industry was one of the largest in the United States. As moving pictures captured the attention of the nation, Hollywood needed centrally located distribution centers to disperse these films to theaters across the country. Given its geographic location and its status as a distribution and transportation hub at this time, Kansas City was perfectly suited to this purpose. Thus, Film Row was born.

Film Row refers to four-square blocks, consisting of 20 warehouses and offices, at the heart of the district we now know as the Crossroads. From the 1920s to the 1960s, every major studio, and several minor ones, all had an office near 18th & Wyandotte. Among them were MGM, Paramount Pictures, Universal, and Warner Brothers. Similarly of note, there were a number of businesses with offices and warehouses near this district that, while not film distribution centers, were similarly linked to the movie theater industry. Most famous among these was the Manley Popcorn Company. Kansas City’s Film Row was one of the largest Hollywood distribution districts in the nation. Considering that the majority of those old buildings are still standing, it is considered the largest, and most intact Film Row, in the nation. Strangely, little has been done to celebrate that history and the district lacks a formalized plan for preservation.

As the 1920s turned into the 1930s, Hollywood was booming. Seemingly, this pocket of Los Angeles was the one place in America that was immune to the Great Depression. In spite of economic hardship, it is estimated that 80 million Americans went to the movies each week during the 1930s. Many postulate that this has tod with how cheap it was to catch a flick. Others would say that the movies and musicals of Hollywood provided an escape from the tough realities of the Depression, if even for a few hours per week. Regardless of the reason, Hollywood flourished during this decade, a period often considered its Golden Age. At the center of all that prosperity was Kansas City.

Sure, as established, Kansas City was a major distribution hub essential to Hollywood’s success. More than that, Kansas City contributed to the on-screen product. When people crowded into theaters to watch a film reel that had passed through a KC warehouse, the chances were quite high that one of the stars in the movie they were watching was also from this city. During Hollywood’s Golden Age, some of the greatest stars of Hollywood actually had ties to Kansas City. In fact, some of the greatest actresses in cinema history, once called Kansas City home.

Shown here in 1936’s Show Boat, Wichita native Hattie McDaniel often portrayed cooks, slaves, and maids (as did many black actors and actresses of the era) but her comedic timing and the dignity with which she carried herself, often led to her stealing the show.

Kansas’ Hollywood Star

Hattie McDaniel (1893 - 1952)

In the Golden Age of Hollywood, there was perhaps no barrier breaker more important than Hattie McDaniel. McDaniel was born in Wichita, Kansas in 1893. She was the youngest of 13 children, and the child of two former slaves. When Hattie was seven years old, the family moved to Colorado. While a student at Denver East High School, Hattie McDaniel began performing as a singer, dancer, and comedienne in minstrel shows.

It was the stage where Hattie McDaniel would begin her professional career after graduation, touring with a black ensemble for much of the early 1920s. In 1925, McDaniel became one of the first African-American women to sing on the radio when she made her debut on Denver’s KOA. Then, in 1926, Hattie McDaniel came to Kansas City where she recorded her first album with the short-lived record label, Merritt. She would have a number of recording sessions with Chicago-based labels in the years that followed. As the 1920s drew to a close, McDaniel landed her first major stage role as Queenie in a traveling production of Show Boat. Unfortunately, before her tour could even begin, the Stock Market Crash of 1929 ushered in the Great Depression and put McDaniel’s acting career on hold. After a couple years of working as a washroom attendant, and later a regular performer, at a nightclub in Milwaukee, McDaniel decided to move to Los Angeles in 1931.

At this time in Hollywood, most of the roles that existed for black actors and actresses were those of subservient positions such as farm workers and maids. Tragically, it was a case of art imitating the reality of society at the time. McDaniel’s first role in Los Angeles was playing a maid on the radio. The role paid her so little, she was forced to also work as a maid in real life just to support herself. In 1932, McDaniel was able to break into film in a series of uncredited roles where, unsurprisingly, she played a maid or cook.

In 1934, McDaniel got her first big break when she landed her first major role in the Will Rogers’ film, Judge Priest. McDaniel impressed as Aunt Dilsey and Judge Priest was a box office success. Those opened the door for Hattie to more film roles, but unsurprisingly, she was primarily typecast as a cook, slave, or maid. In 1935, she appeared in China Seas as a traveling companion to the female lead, played by Kansas City’s own Jean Harlow. In 1936, she had a pair of minor roles in films headlined by Independence, Missouri native Ginger Rogers (more to come on these two Hollywood starlets later). That same year, McDaniel would finally get the chance to play Queenie in Show Boat; this time it came on the silver screen. Hattie McDaniel starred alongside some of the biggest names in Hollywood history and, oftentimes, her performances were so strong that she would steal the scene. Her prowess as an actress and a singer earned her the respect of several Hollywood legends, whom she would later consider lifelong friends.

One of those friendships was reportedly a big factor in her landing the role that would define her career. In the late 1930s, Selznick International Pictures acquired the rights to make Margaret Mitchell’s classic novel, Gone With The Wind, into a feature film. The competition for the role of Mammy, a plantation house slave, was so intense that First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt reached out to the director insisting that her own maid at the White House be given the part. To this point in her career, McDaniel had primarily been a comedic actress, but thanks in part to, supposedly, an endorsement from Clark Gable who she had worked with on China Seas, Director David O. Selznick ultimately chose McDaniel for the role.

“Hattie McDaniel is a terrific actress and so often relegated down in the credit roll but her performance, in many of these movies, is the performance that you remember.”

Gone With The Wind became one of the most celebrated films of all time. It earned 13 Academy Award nominations, among them was Hattie McDaniel, nominated for Best Supporting Actress. Had McDaniel not approached Selznick armed with glowing reviews for her performance, it would have likely only been 12. Gone With The Wind’s own director was not considering submitting her name prior to that confrontation. By doing so, Hattie McDaniel became the first black actor or actress to be nominated for an Academy Award.

In 1999, the new owners of Hollywood Cemetery decided to honor Hattie McDaniel’s final wish, best they could, by installing a memorial to her, 47 years after her death.

For McDaniel, she had been clearing hurdles her entire career. When Gone With The Wind made its premiere at Loew’s Grand Theatre in Atlanta, McDaniel was barred from attending due to the state’s segregation laws. Clark Gable reportedly threatened to boycott the event in solidarity with McDaniel, but she insisted that he attend. Fortunately, she was able to attend the Hollywood premiere.

When the night of the 12th Annual Academy Awards arrived, Hattie McDaniel dressed to impress. She showed up in a beautiful turquoise dress, donning a sash of white flowers. However, on that night, she would once again feel the cruel sting of segregation. The site of the awards, the famous Coconut Grove Nightclub in Los Angeles, did not permit blacks. While Selznick was able to get the club’s owner to lift the ban for McDaniel, she was not able to sit at a table with her co-stars. Instead, she was relegated to a lone table at the back of the club where only her date, and her white agent, joined her.

Gone With the Wind would win 10 Academy Awards on that fateful night. Among those, and of the utmost significance, was the Best Supporting Actress Award. Hattie McDaniel had become the first black person to ever win an Academy Award. When McDaniel took the stage, she famously said, “I shall always hold it as a beacon for anything that I may be able to do in the future. I sincerely hope that I shall always be a credit to my race and to the motion picture industry. My heart is too full to tell you just how I feel, and may I say thank you and God bless you.”

McDaniel’s win was not without controversy. Southern white audiences were angered by the familiarity that McDaniel’s characters had with white leads on screen and the way the characters she portrayed often interacted with white leads in her films. Many times, they were angry because she would steal the scene from white actors. Similarly, many black people saw her Oscar win as bittersweet. Black audiences, and civil rights organizations like the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), felt that McDaniel profited off perpetuating negative stereotypes of African-Americans. While McDaniel understood the criticism, she never let it bother her. She was quoted on multiple occasions as saying, “Why would I complain about making $700 a week playing a maid? If I didn’t, I would make $7 a week being one.”

“Why would I complain about making $700 a week playing a maid? If I didn’t, I would make $7 a week being one.”

In the aftermath of her Oscar win, McDaniel was very successful. However, many claim that, due to her generosity to those less fortunate, she was often broke. Over the course of her career, McDaniel appeared in nearly 100 movies. In the 1940s, she starred on radio’s The Beulah Show. She was starting to make the transition to television in 1952 when she was diagnosed with breast cancer. She passed away later that year. At the time of her death, McDaniel had asked to be interred at Hollywood Cemetery. Despicably, segregation struck once more and prevented the fulfillment of her final wish. She was buried at Angelus-Rosedale instead. Posthumously, McDaniel was awarded two stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame - one for her work in film, and the other for her work in radio.

While McDaniel broke through a glass ceiling with her win in 1940, it was not until 1964, when Sidney Poitier won Best Actor, that another black person would win an Oscar. When Whoopi Goldberg won Best Supporting Actress for Ghost in 1990, that was the first time a black woman had won an Oscar since McDaniel’s win. However, the contributions of McDaniel to the motion picture industry are still felt today.

In 2010, when Mo’Nique won Best Supporting Actress for her work in Precious, she took the stage, dressed in a blue gown, with a white gardenia in her hair, an obvious homage to McDaniel. She fought back tears as she told the crowd, “I want to thank Miss Hattie McDaniel for enduring all that she had to, so that I would not have to.” There can be no doubt, that for many, McDaniel was a credit to women, she was a credit to her race, she was a credit to the motion picture industry, and most of all, Hattie McDaniel was a credit to humanity.

So, What Do I Do? Hattie McDaniel’s time in Kansas City was incredibly short-lived so there is virtually nothing here to honor her. Her birthplace of Wichita, Kansas, and even Hollywood, do a much better job in that regard. In general, my advice would be to check out the Black Archives of Mid-America to learn more about the number of amazing black men and women, like McDaniel, who broke barriers and made a difference in Kansas City and beyond.

In 1940, Hattie McDaniel became the first African-American to win an Oscar, taking home Best Actress in a Supporting Role for her portrayal of Mammy in Gone With The WInd. While the moment represented a broken barrier, McDaniel’s win, and the roles she played, were not without controversy. PHOTO CREDIT - Bettman Archive

Kansas City’s Blonde Bombshell

Jean Harlow (1911 - 1937)

It would seem that as long as there has been a Hollywood, there has been a tradition of the “bombshell” and its most common use, “the blonde bombshell”. A term that has been used over time to refer to actresses with sex appeal and larger-than-life personalities, the label has found a way to last in cinema vernacular. Typically, the etymology of slang terms is conflicted with multiple origin stories and differing accounts of creation. However, when it comes to the “blonde bombshell”, every person versed in the history of Tinseltown agrees that the term originates with one actress. Long before there was Marilyn Monroe, Jayne Mansfield, or Farrah Fawcett, there was the Hollywood starlet who was first known as a blonde bombshell, Jean Harlow.

Harlow was born Harlean Carpenter on March 3, 1911 in Kansas City, Missouri to Mont Clair Carpenter, a dentist, and Jean Harlow Carpenter. Her mother was the daughter of local real estate tycoon Samuel D. “Skip” Harlow. As a young girl, Harlean attended the Barstow Finishing School in Westport until 1922, when Harlean’s mother divorced her father and moved with Harlean to Los Angeles to pursue an acting career.

Harlean then attended another finishing school in Hollywood but dropped out when she was 14. Shortly after, she moved back to Kansas City with her mother after Skip said he would disinherit his daughter and granddaughter if they did not return home. At the age of 16, Harlean got married for the first time, eloping with a wealthy young baker named Chuck McGrew. Not long after the wedding, the couple moved to Beverly Hills where the couple enjoyed life as unemployed socialites. It was while running in those circles, that Harlean befriended Rosalie Roy and, unknowingly, changed the trajectory of her life.

Rosalie was a young actress and without a car. While dropping Rosalie off at Fox Studios for an audition, Harlean caught the eye of studio executives who asked her to come in and read for a part. Initially Harlean was not interested in an acting career; at the insistence of Rosalie, and her mother who had aspired to be an actress, she went in to audition at Fox Studios and gave her mother’s name, “Jean Harlow”.

“I wasn’t born an actress, you know. Events made me one.”

Harlow landed a role as an extra in the film Honor Bound and proceeded to appear in a number of Laurel and Hardy comedy shorts in various roles. Her husband strongly opposed Harlow’s acting career which, ultimately, led to the couple’s divorce in 1929.

That same year, eccentric aviator and film producer Howard Hughes, was reshooting his war epic Hell’s Angels for sound. The original female lead, Greta Nissen, was determined to be inappropriate for a talking picture due to her heavy Norwegian accent. While starring in The Saturday Night Kid, Jean Harlow had caught the eye of Hell’s Angels’ actor James Hall who recommended Hughes enlist her to play the part of Helen. When Hell’s Angels premiered in 1930, it made Jean Harlow, who Hughes’ press agent had billed as “The Blonde Bombshell” and “The Platinum Blonde”, an international sensation overnight. Her success was followed by starring roles in films such as The Secret Six, The Public Enemy, Platinum Blonde, Bombshell, The Girl From Missouri, and China Seas.

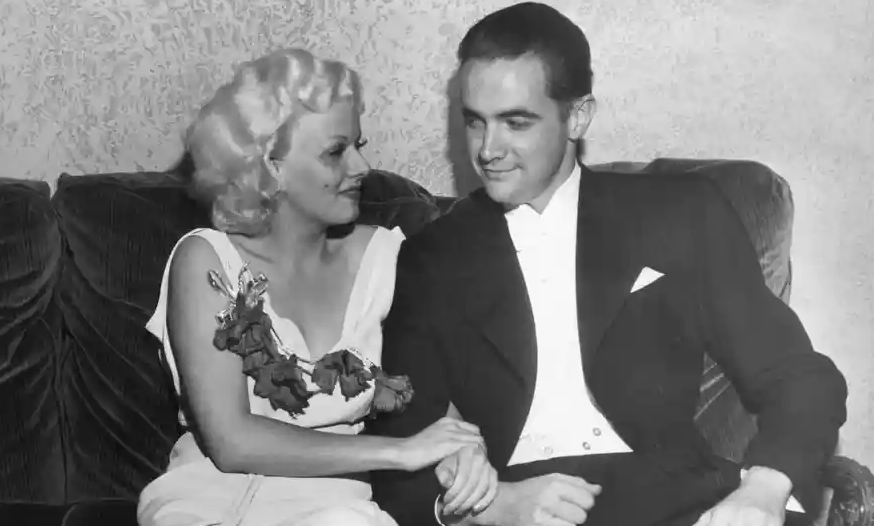

Jean Harlow (left) pictured with aviator and movie director/producer Howard Hughes (right). Howard Hughes’ decision to re-shoot Hell’s Angels for sound and re-cast the female lead made Jean Harlow a star overnight. PHOTO CREDIT - Bettman Archive

“No matter what I do, I always end up on page 1!”

In 1932, Jean Harlow wed for the second time, this time to MGM Executive Paul Bern. Earlier that year, Bern had been successful in buying out Harlow’s contract from Howard Hughes and signing her to an exclusive deal with MGM. Fay Wray, who famously starred as Ann Darrow in King Kong, later disclosed that she only got the iconic role because Harlow’s deal with MGM prevented RKO Pictures from casting their preferred choice. Harlow’s marriage to Paul Bern ended abruptly when he was found dead two months after their wedding in what was eventually, though controversially, ruled a suicide.

Following Bern’s death, Harlow had an affair with Max Baer, eventual Heavyweight Boxing Champion, who was still married. In an effort to avoid negative press, studio executives arranged for Harlow to get married a third time. Her marriage to cameraman Harold Rosson, like her previous two, was short-lived and ended in divorce after six months.

There was always something larger-than-life about Jean Harlow. She was a beautiful actress whose on-screen persona captured the attention of audiences around the world. She had a rare combination of comedic timing and dramatic presence that opened her up to a variety of roles. Off the screen, she seemingly captured the attention of wealthy heirs, professional athletes, the Hollywood elite, and purportedly, Howard Hughes. She wore the latest fashions, dazzling jewelry, and drove her iconic red Cadillac. Crazy enough, she was even considered a godmother for famed mobster Bugsy Siegel’s daughter! Harlow notably quipped, “No matter what I do, I always end up on page one!”

Jean Harlow (right) pictured at Kansas City’s Union Station with her mother, “Mama Jean” (center), and her grandmother (left). Harlow visited Kansas City often throughout her career.

In 1937, Jean Harlow was cast opposite Clark Gable in Saratoga. During filming, Harlow developed a mysterious illness. Co-star Clark Gable would later remark that Harlow’s breath smelled of urine during this time. Few were alarmed as Harlow had battled through one illness after another for most of her life. Having already delayed filming once, Harlow, somehow, powered through and continued filming for another week and a half until the pain became too severe.

On June 6, 1937, Harlow slipped into a coma and the following day, she passed away at the age of 26. The cause of death was diagnosed as kidney failure, and believed to have been a long-term result of contracting scarlet fever in her teenage years. Some contend that it had to do with the toxic process Harlow utilized to dye her hair its signature color that was already causing hair loss at the time of her death. And others blame her socialite lifestyle and the heavy alcohol consumption that accompanied it. Regardless of the cause, one of Hollywood’s brightest stars had sadly faded away just as quickly as she had risen.

Following Harlow’s death, MGM found a way to complete the film, utilizing body and voice doubles. It became the highest-grossing film of The Platinum Blonde’s career, and many critics consider it to be her best performance.

For seven years in the Golden Age of Hollywood, Jean Harlow was Hollywood’s “It Girl”. Between 1930 and 1937, she appeared in 24 films and captured headlines every step of the way. She was posthumously awarded a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 1960 and in 1999, the American Film Institute (AFI) ranked Harlow number 22 on their list of Greatest Female Screen Legends over their first 100 years. While Jean Harlow’s life was tragically cut short, she lived more in 26 years than many do in a lifetime. The Girl From Missouri’s comedic presence, larger-than-life persona, and yes, her signature hair color, would inspire generations of actresses to come.

So, What Do I Do? Someone who was very much from Kansas City and often returned, Jean Harlow’s presence is still felt here but once again, very little to publicly honor her. Her childhood home at 1312 East 79th Street in Kansas City, Missouri is still standing, but this is a private residence. Notably for KCK residents, Jean Harlow is one of “Johns” featured prominently on the ceiling of the local dive bar, Johnnies on 7th. Additionally, if you visit the Nelson Atkins Museum of Art, it is believed that the woman that is front and center in local artist, Thomas Hart Benton’s “Hollywood” (1937) is in fact, Jean Harlow.

Jean Harlow starred alongside Clark Gable in China Seas. Hattie McDaniel also had a role in the film as Dolly’s (Harlow) maid.

Kansas City’s Leading Lady

Ginger Rogers (1911 - 1995)

As fate would have it, the same year, 1960, that Jean Harlow received her star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, another actress from Kansas City would receive hers as well. Most often remembered for the movie-musicals that she starred in with Omaha, Nebraska native Fred Astaire, Ginger Rogers was much more than half of this iconic duo. Coincidentally, this Kansas City actress with a storied career, was born the same year as Jean Harlow too.

The house in Independence, Missouri where Ginger Rogers was born is still standing today.

Ginger Rogers was born Vinginia Katherine McMath on July 16, 1911 in Independence, Missouri. Having lost a previous child while in labor at a hospital, Virginia’s mother Lela, a reporter for an Independence newspaper, insisted on giving birth to her in their small two bedroom home. While Virginia would never have any siblings, she was incredibly close to her cousins on her mother’s side. Some of her younger cousins struggled to pronounce Virginia’s name and called her “Ginja”. The name stuck.

Shortly after Ginger was born, Lela separated from Ginger’s father William McMath. After McMath kidnapped his daughter on a couple of occasions, Lela finalized the divorce in 1914. Ginger would never see her birth father again. In 1915, Lela took Ginger to nearby Kansas City, Missouri to live with her grandparents while Lela headed to Hollywood in pursuit of a career in screenwriting. In 1917, Lela succeeded in getting one of her essays adapted into Fox Studios’ film, The Little Patriot. Lela stayed in Hollywood to continue writing scripts for Fox, although she returned to Kansas City frequently to visit her daughter.

In 1920, Lela married John Logan Rogers and they, along with Ginger, moved to Fort Worth, Texas. While her stepfather would never formally adopt her, Ginger took the Rogers surname.

Lela Rogers took a job as a theater critic for the Fort Worth Record. As a result of Lela’s job, Ginger would often accompany her mother to theaters such as the famed Majestic Theater in Dallas. It was here that Ginger received her first exposure to live theater, often waiting in the wings, watching the players, and teaching herself to dance.

In 1924, while a student at Central High School in Fort Worth, Ginger entered into and won a statewide Charleston dance contest. Winning the contest thrust young Ginger into a six-month long vaudeville tour of the Orpheum Circuit. Ginger dropped out of school and seized the opportunity. Lela joined her daughter on tour. When her vaudeville circuit came to an end, Lela and Ginger toured on their own.

In 1928, Ginger’s tour brought her and Lela to New York City where they decided to stay. While in pursuit of a Broadway role, Ginger sang on the radio to support herself. In 1929, she landed her first role in the musical Top Speed. Within a month of Top Speed’s opening, Ginger was named the lead in Girl Crazy. Ginger was only 19 years old and she was already the talk of Broadway.

Around the same time that she was wowing Broadway audiences, Ginger was making her transition to the silver screen. With Paramount Pictures having studios in Long Island, Ginger took a bit part in Young Man of Manhattan. After small roles in a subsequent pair of films for the studio, Ginger Rogers landed a seven-year deal with Paramount Pictures. Between 1930 and 1931, she made five more movies for Paramount Pictures. In 1931, Ginger’s mother, who served as her agent, helped get her out of the Paramount deal. The pair then made their way west to a place that Lela knew very well - Hollywood.

“Rarely have I known a closer mother-daughter relationship [than Lela and Ginger Rogers].”

During her first couple of years in Hollywood, Ginger made a number of films for a number of studios. In 1933, she signed on with RKO Studios. Her first film with the studio, Flying Down to Rio, was a movie-musical that paired Ginger Rogers with the choreographer from Girl Crazy, Fred Astaire.

This pairing would usher in a renaissance of Hollywood movie-musicals and forever define cinematic dance sequences and the manner in which they were both choreographed and filmed. The dancing duo was very much a case of yin and yang. Astaire was a lanky, balding actor with an air of European sophistication about him. While a bit awkward as an actor, he had an impeccable sense of rhythm; that, combined with a precise choreography technique, made him a phenomenal dancer. Meanwhile, Ginger Rogers was a beautiful, charismatic actress who could easily transition back and forth between comedic and dramatic. Audrey Hepburn famously remarked that, “Astaire gave her class. Rogers gave him sex.” While initially, Ginger was considered to be a hair behind Astaire in dancing technique, she soon closed that gap. Some would even say she surpassed Astaire. After all, as Ginger Rogers would often say, she did everything that Fred Astaire did, only “backward and in high heels.”

The combination of on-screen compatibility between Rogers and Astaire immediately resonated with audiences. The complexity, elegance, and syncopation of their dance numbers dazzled. After the success of Flying Down to Rio, Rogers and Astaire starred in The Gay Divorcee in 1934. In the film, the couple introduced audiences to a dance called The Continental. A song that accompanied the dance, of the same name, was sung by Rogers. The Continental would go on to win the first ever Academy Award given for “Best Original Song”.

“Astaire and Rogers. Their names will likely be paired as long as there are movies; as long as people dance.”

During her time at RKO Pictures, Ginger Rogers made seven more movie-musicals with Astaire. These were Roberta (1935), Top Hat (1935), Follow the Fleet (1936), Swing Time (1936), Shall We Dance (1937), Carefree (1938), and The Story of Vernon and Irene Castle (1939). Top Hat was the first movie written exclusively for the iconic duo. It was RKO Pictures’ highest grossing film of the 1930s earning over $3.2 million worldwide. Ginger Rogers would later tell Katie Couric in a 1991 interview for The Today Show that Top Hat was her favorite movie that she ever made with Astaire.

1935’s Top Hat was the first film written exclusively for Ginger Rogers and Fred Astaire. Rogers would later recount that this was her favorite movie that she did with Astaire.

In 1933’s Gold Diggers, Ginger Rogers famously sang the song We’re In The Money during the film’s opening credits. However, during her time at RKO pictures, in spite of the duo being box office gold, there was no “we” about it. Fred Astaire was in the money, while Ginger Rogers was not. Not only was Ginger Rogers paid less than Fred Astaire, who also received ten percent of each film’s profits as choreographer, she was often paid less than many of the supporting actors in their films. This created friction between Ginger Rogers and Mark Sandrich, who directed a majority of the duo’s films. In 1939, due in part to the way Sandrich treated her, and in part to her desire to pursue dramatic roles, Ginger Rogers stepped away from musicals.

While Rogers had shown an aptitude for dramatic acting with films like Vivacious Lady, which also featured Katherine Hepburn and Hattie McDaniel, and Fifth Avenue, alongside James Stewart, it was her role of the title character in 1940’s Kitty Foyle that established Rogers as a premiere dramatic actress. For the role of Kitty Foyle, Ginger Rogers won the Academy Award for Best Actress in 1941. By 1942, she was one of Hollywood’s biggest stars, earning over $350,000 per year. Notably, Ginger Rogers was also fiercely political. She was a proud member of Daughters of the American Revolution. In 1948, she stood in staunch opposition to fellow Independence, Missouri native, President Harry S. Truman, when she openly campaigned for New York Governor Thomas Dewey.

In 1949, Ginger Rogers would reunite with Fred Astaire for one last film together, The Barkleys of Broadway. While audiences were often convinced of it due to their cinematic chemistry, Ginger Rogers and Fred Astaire were never romantically involved. However, it might be fair to say that her partnership with Astaire was her most successful one. Ginger Rogers married five times throughout her life, taking her first husband when she was only seventeen, but none of those marriages lasted as long as her pairing with Astaire. That may not even be fair to say. After all, until her death in 1977, Lela Rogers served as her daughter’s agent. The incredibly close kinship of mother and daughter was undoubtedly Ginger Rogers’ most successful relationship. Although Ginger Rogers and Fred Astaire would remain close friends. In 1950, when Fred Astaire was award an Academy Honorary Award, it was Ginger Rogers who presented it to him.

“Ginger was brilliantly effective. She made everything work fine for her. Actually, she made things very fine for both of us and she deserves most of the credit for our success.”

In the 1950s, Ginger Rogers’ stardom began to fade, but that did not prevent her from making movies. She often credited her workout regimen, which largely included playing tennis and swimming regularly, for the way that many claimed that Ginger defied aging. In 1952, she won the Golden Globe for Best Actress for her work in Monkey Business. In 1965, Ginger Rogers was cast in her 73rd and final film, Harlow in which she played “Mama Jean”, the mother of legendary actress Jean Harlow. Because, who better to capture the very close relationship between a famous actress from Kansas City and her mother with Hollywood dreams than Ginger Rogers?

That same year, Ginger Rogers career came full circle when she returned to the Broadway stage to star in Hello Dolly! She sold out every single show. Throughout the 70s and 80s, Ginger Rogers made a few cameo appearances on television shows. In 1985, she fulfilled a lifelong dream of directing when she directed an off-Broadway production of the musical comedy, Babes in Arms. In 1991, Ginger Rogers added “author” to her amazing list of accomplishments when she published her autobiography Ginger: My Story.

Ginger Rogers passed away in 1995 at Rancho Mirage, a California ranch she had purchased in 1939. She was buried at Memorial Park Cemetery next to her mother. Before her death, Ginger Rogers would return to Independence, Missouri one final time. In 1994, she returned home for Ginger Rogers Day. In one of her final public appearances, she signed over 2,000 autographs for locals, as the house where she was born, at 100 W. Moore Street, was designated as a Historic Landmark Property. In 1999, when the AFI named their Greatest Female Screen Legends, they ranked Ginger Rogers fourteenth on the list.

Tragically, Ginger Rogers often gets remembered merely as Fred Astaire's dance partner, but she was so much more than that! Not only could Rogers keep up with Astaire “backwards and in high heels”, she was unique in that, unlike the overwhelming majority of dancers in these movies, she never stopped acting when the number began. It has been said that, women of that era dreamed of dancing with Fred Astaire because Ginger Rogers made it look so thrilling. When Rogers was asked in a 1991 interview whether she got enough credit for her role in her films alongside Fred Astaire she bluntly stated, “This is a man’s world, or at least so it is at the moment. And at that time, it certainly was too. So what would you expect? You wouldn’t expect them to like me over a man would you? Never.” Even Astaire would have agreed. As he once put it, “[Ginger Rogers] deserves most of the credit for our success.” She definitely does not deserve to be relegated to the role of sidekick in the annals of Hollywood history. Ginger Rogers was a singer, dancer, author, and director. She was a dramatic actress and a comedienne who won both an Oscar and a Golden Globe. She was one-half of the greatest dancing duo that cinema has ever known. She was jointly responsible for ushering in the heyday of Hollywood movie-musicals. A star of the vaudeville circuit, Broadway, and Hollywood, Ginger Rogers was every bit a leading lady.

So, What Do I Do Now? First of all, visit Film Row in the Crossroads (18th & Wyandotte) where Ginger Rogers and Jean Harlow both have stars on a Kansas City Walk of Fame of sorts. Ginger Rogers’ birthplace (100 W. Moore Street in Independence, Missouri) still survives as a Historic Landmark Property. It is privately owned. A few years ago, it was converted to a museum dedicated to her career but sadly, due to a general lack of interest and issues arising from the COVID-19 pandemic, it was forced to close down recently. The memorabilia collection that the museum housed was reportedly donated to a group who hopes to open a museum dedicated to celebrities and historical figures from Jackson County, Rogers and Jean Harlow among them, but that remains to be seen.

For her work in 1940’s Kitty Foyle, Ginger Rogers won the Academy Award for Best Actress. PHOTO CREDIT - imdb

While I chose to write about McDaniel, Harlow, and Rogers, this does not even begin to scratch the surfaces of stars with a connection to Kansas City. This does not even account for everyone from that era!

Joan Crawford, who won the Academy Award for Best Actress for her work in 1945’s Mildred Pierce, lived in the Historic Northeast during her teenage years. She even worked at Emery Bird and Thayer in downtown Kansas City as a salesgirl. A veteran of over 80 films, the AFI considers Crawford to be the tenth greatest female screen legend of film’s first 100 years. As decorated as Crawford is as an actress, she is often remembered now for the strained relationship with her two oldest children that led her daughter Christina to publish an expose titled Mommie Dearest, the year after Crawford passed. Similar to Rogers and Harlow, Crawford is remembered with a Star in both Hollywood and Kansas City’s Film Row.

A poorly maintained Walk of Fame at 18th & Wyandotte remembers some of the film giants of Kansas City. Jean Harlow, Joan Crawford, and Ginger Rogers are among them.

Hattie McDaniel’s career began, and ended, on the airwaves. Kansas City produced a number of stars in that regard as well. Unsurprisingly, a number of legends of jazz passed through Kansas City. While America’s original artform was born in New Orleans, Kansas City is where jazz grew up and came into its own. Kansas City is the birthplace of bebop and the “jam session sound”. Julia Lee was a prolific blues, jazz, and R&B singer of the 1920s - 1940s with lifelong ties to KC. Mary Lou Williams, a prolific composer and jazz pianist, came to Kansas City with Andy Kirk’s Twelve Clouds of Joy in the late 1920s. She famously wrote and arranged music for Duke Ellington and Benny Goodman. Jazz singer Myra Taylor was born in Bonner Springs, Kansas and raised in the 18th & Vine District of Kansas City during its heyday. The famous singer had a few acting credits to her name as well, notably Scoring (1979), and was a lifelong Kansas Citian. In 2011, she famously celebrated her 94th birthday by putting on a show at Knuckleheads Saloon in the East Bottoms.

Whether it be the silver screen, small screen, or the airwaves, there is a tradition of female stars from Kansas City that has continued on to this day. In the 1970s, 1980s, and into the 1990s, actresses Nora Denney (Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory), Dee Wallace (E.T. the Extra Terrestrial), Julia Montgomery (Revenge of the Nerds), and two-time Academy Award Winner for Best Supporting Actress, Diane Wiest (Edward Scissorhands), were all Kansas City-area actresses who made it in Hollywood.

Gillian Flynn, who is most famous for writing the novel Gone Girl and also wrote the screenplay for the 2014 film of the same name, was born and raised in midtown Kansas City, Missouri. Eight-time Grammy Award winner Janelle Monae, who is also known for her roles in Moonlight and Hidden Figures, is a Kansas City, Kansas native who grew up around Quindaro. Ellie Kemper (yes, the Commerce Bank Kempers), who is remembered as Erin Hannon in The Office and the starring role in Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt, is also a KC native.

Lynn Cohen (The Hunger Games: Catching Fire), Ashleigh Murray (Riverdale), Bebe Wood (The New Normal and Love, Victor), Heidi Gardner (Saturday Night Live), Fabianne Therese (Teenage Cocktail), Sarah Lancaster (Chuck), and Vanessa Merrell (Jane The Virgin) are all actresses who are native to the Kansas City metro. While there are names I am likely still neglecting, it is evident to see that the pipeline of female talent from Kansas City to Hollywood still exists today.

When you travel outside of the United States, there is one thing that becomes abundantly obvious - the chief export of the United States is pop culture. While we rarely think about it, our movies and music are everywhere. We often call jazz the true American artform, but in many ways the same can be said of cinema. Much like jazz, the Golden Age of movies was shaped, in significant part, by artists who found their voice and their calling in Kansas City. And in the particular case of Ginger Rogers, Hattie McDaniel, and Jean Harlow, among others, these women of Cowtown became Legends of Tinseltown, who continue to inspire.

Together, these stars of the silver screen add their own verse to this city’s herstory.

Join me next week, as we continue of exploration of Kansas City’s herstory and the amazing women who made our city what it is today.

Subscribe to disKCovery to be the first to know when the final installment, “Herstory of the City, Part V” drops.

Have a favorite icon of Kansas City herstory? Or maybe a fun fact or tidbit about the Hollywood starlets of Kansas City? Let me hear it in the comments!

Many thanks to my mother, Janell Dignan, for proofreading and editing these stories. I would not have pulled off finishing this series without you!