Fantasy Baseball - Part 2

NOTE: This is the second half of a piece about a fictional baseball match-up between a team of all-time great Kansas City Monarchs players, and the team of legendary players detailed below. If you have not already read Part I, I would encourage you to CLICK HERE and do so prior to reading this.

Began the same year as Major League Baseball’s All-Star Game, the Negro Leagues’ East-West All-Star Game was often a bigger draw. Pictured is the East Team from the 1948 game. PHOTO CREDIT - Ernest C. Withers, Public Domain

Published April 15, 2025

“Baseball gives every American boy a chance to excel … “

I know I had my chances to shine on the diamond when I was younger. I just didn’t. But, man, I loved to play! My game had its share of shortcomings, but one moment stands above the rest.

At eight years old, I was the catcher for my T-ball team. (Let’s be honest, you’ve got to be pretty lousy to be the catcher in T-ball.) We were playing in Jefferson, Missouri, and the other team had runners on first and second. The batter stepped up and cracked a shot into the right field gap. As the runners took off, the crowd cheered, but all I could hear was my dad’s gravelly voice from the bleachers. “COVER HOME, DEVAN! COVER HOME!”

Clearly, I was the greatest defensive backstop in the game. PHOTO CREDIT - disKCovery

I spun around, completely confused. “What could he mean?” I wondered, “Cover home?” My dad locked eyes with me, pointed towards the plate, and again he yelled, “COVER HOME!”

In a moment of panic, and youthful logic, I dropped to all fours, doing my best cat-like loaf to “cover home” as the first runner rounded third. No way they were going to score on my watch! But there I was, sprawled in the dirt, the fans laughing, while two runners - just as confused as I was - stood near the plate, watching their teammate safely reach second.

Of course, my defensive maneuver wasn’t exactly legal, and the runs counted. But looking back, as embarrassing as it was, I can at least understand how my eight-year-old brain tried to make sense of the game. There’s some things about baseball that I’ll never fully get.

“Baseball gives every American boy a chance to excel, not just to be as good as someone else, but to be better than someone else.” Or at least, it should.

When Ted Williams stood at the podium in Cooperstown in 1966, he acknowledged that baseball hadn’t always given every American that chance. For over sixty years, African American players were barred from the Major Leagues (MLB). No official rule, just an unwritten code among team owners that black players were not welcome. When the doctrine was rarely mentioned, it was ironically called “a gentlemen’s agreement.” I’ll never understand how exclusion could be considered gentlemanly.

For nearly forty years, the best black players barnstormed, traveling from town to town, playing exhibition games against any team who’d have them. Then, in 1920, black baseball got organized. Rube Foster and seven other team owners met at the Paseo YMCA in Kansas City, Missouri and formed the Negro National League. During the offseason, players still barnstormed, or played in Latin America. But come spring, they represented their cities: chasing pennants, competing for World Series titles, and even earning selections to their own All-Star Game.

The East-West All-Star Game, created by Gus Greenlee (owner of the Pittsburgh Crawfords) in 1933, showcased the best of black baseball. Instead of letting sportswriters handle the selection, Greenlee brilliantly published ballots in the Chicago Defender and Pittsburgh Courier to allow the fans to decide. Selected All-Stars were assigned to teams based on the geographic location of their teams, not the league they belonged to. Each player wore the uniform of the team they represented. Played at Comiskey Park in Chicago, the game drew over 50,000 fans at its peak, outpacing the MLB’s All-Star Game during baseball’s era of segregation.

“That was a pretty important thing for black people to do in those days, to be able to vote, even if it was just for ballplayers, and they sent in thousands and thousands of ballots. It was like an avalanche!”

For decades, the greatest black athletes were confined to the Negro Leagues, never given the chance to be better than those in the Majors. Then, in 1947, Kansas City Monarchs’ star Jackie Robinson broke through the color barrier with the Brooklyn Dodgers. That same season, Larry Doby (Newark Eagles), Hank Thompson (Monarchs), Willard Brown (Monarchs), and Dan Bankhead (Homestead Grays) followed him to the Majors. Finally, the color line was broken. It would take 12 years for all teams to integrate, but at long last, every player had a chance.

Years later, Ted Williams believed Negro League players were owed a chance at baseball immortality as well. On that day of his Hall of Fame induction, he used his platform to advocate on their behalf. “And I hope that someday the names of Satchel Page and Josh Gibson in some way can be added as a symbol of the great Negro players that are not here, only because they were not given a chance.” Five years later, Williams got his wish. [1]

As James “Cool Papa” Bell put it, “Some people say I was born too early, but that’s not true, they opened the doors too late.”

And that’s just too absurd for this kid who covered home plate to ever understand.

Part II: The East-West All-Stars

I close my eyes and the perfect game comes into focus. As I watch the Monarchs’ legends of yesteryear warm up, I begin to wonder: who could possibly occupy the third base dugout for this game?

Whispers ripple through the crowd about the day’s opponent. I catch snippets of a nearby conversation where a “super team” is mentioned. I even hear a rumor about the visitors flying in on their own plane, the star pitcher’s name boldly painted on its side. As I look around the grandstands, I notice that sprinkled among the Monarchs’ faithful are those waving pennants of teams from Pittsburgh, Chicago, Newark, and New York.

“There’s a couple of million dollars worth of baseball talent on the loose, ready for the big leagues yet unsigned by any major league clubs. ... Only one thing is keeping them out of the big leagues - the pigmentation of their skin. They happen to be colored. That’s their crime in the eyes of big league club owners.”

And then, it hits me. This game cannot be perfect if it only celebrates the best of the Monarchs. There are so many other legends, who never represented Kansas City; giants of the game who never had their shot. I similarly dream of seeing them play.

Much like Gus Greenlee’s brainchild at Comiskey Park, Muehlebach Field must be a stage to honor them all. Both the players who, as Buck O’Neil would say, “helped build a bridge across the chasm of prejudice”, and those who later crossed that bridge. The only team worthy of facing this talent-laden Monarchs squad is a team stacked with the greatest players across the Negro Leagues.

As a commanding figure in the familiar pinstripes of the Indianapolis ABCs emerges from the opposing dugout and steps into the on-deck circle, my suspicions have been confirmed.

The East-West All-Stars have come to Kansas City.

I take a swig from a bottle of cold Heim Lager, the buzz of the crowd rising, as the PA announcer turns his attention to the visiting team’s line-up.

BUT FIRST, A NOTE FROM THE WRITER: For as much as I revere the Negro Leagues, and love the Kansas City Monarchs, I equally appall the inhumane realities of that time which made a separate league necessary. As many do, I wish these leagues did not have to exist. It is not the intention of this piece to glamourize the atrocity of segregation. Instead, it is to recognize the greatness of these legends, and to think about how special it would have been to see these men play. While I paint a picture that puts the stadium in the 1930s, please remember that this is a game outside of time. The beauty of a fantasy, is that I can picture both a game that is perfect, and societal attitudes that are as well. In regard to the latter, we celebrate Jackie Robinson Day today to acknowledge both how far we have come as a society, and how far we still have to go.

“Leading off for the visiting All-Stars, the center fielder, #40, Oscar Charleston.” [2]

CF | #40 | Oscar Charleston

Indianapolis ABCs (1915 - 1918, 1920, 1922 - 1923)

Oscar Charleston, 1926 (shown here with the Harrisburg Giants)

PAINTING BY: Graig Kreindler, from the collection of Jay Caldwell.

Nickname(s): “Charlie”, “The Hoosier Comet”

Other Notable Teams: Harrisburg Giants (1924 - 1927, 1930 - 1931), Pittsburgh Crawfords (1932 - 1940)

Awards: 2x Eastern Colored League Triple Crown (NgL), 1921 Negro National League Triple Crown (NgL), 3x Negro National League Homerun Champion (NgL), 3x Eastern Colored League Homerun Champion (NgL), 2x Eastern Colored League Batting Champion (NgL), 1921 National League Batting Champion (NgL), Pittsburgh Pirates Hall of Fame, FIRST TEAM: 1952 Pittsburgh Courier All-Time Negro League Team (CF), ROLL OF HONOR: 1952 Pittsburgh Courier All-Time Negro League Team (MGR), Indiana Baseball Hall of Fame (1981), 1998 Sporting News “Baseball’s 100 Greatest Players” (#67), 2020 The Athletic “Baseball 100” (#5)

All-Star Nods: 3x East-West All-Star (NgL)

Rings: 3 (Negro National League Champion - 1933, 1935, 1936)

Hall of Fame: 1976 (USA)

Bats: Left

Throws: Left

Batting Average: .365 [3]

Homeruns: 144

Runs Batted In: 855

Hits: 1,209

Stolen Bases: 210

Runs: 853

WHO’S HE? Alongside the likes of Ty Cobb [4] and Honus Wagner, Oscar Charleston was one of baseball’s earliest five-tool stars [5]. His Hall of Fame plaque celebrates his multi-dimensionality, calling out his terrific “speed, strong arm, and fielding instincts.” Honus Wagner himself declared, “Oscar Charleston could have played on any big-league team in history if given the opportunity. He could hit, run and throw. He did everything a great outfielder was supposed to do.” Often hailed as the greatest centerfielder in Negro Leagues history, Charleston left an indelible mark on the game. Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe even argued that Charleston, “was a better base runner, a better center fielder and a better hitter [than Willie Mays].” Buck O’Neil often echoed that sentiment. “Charlie was a tremendous left-handed hitter who could also bunt, steal a hundred bases a year and cover centerfield as well as anyone before him or since.” New York Giants manager John McGraw said, “If Oscar Charleston isn’t the greatest baseball player in the world, then I’m no judge of baseball talent.” With his unrivaled combination of hitting, power, speed, and defense, Charleston is perhaps the greatest player that most baseball fans have never heard of.

WHY HIM? Oscar Charleston could do it all! Satchel Paige said, “You had to see him to believe him.” It was said that Charleston could cover all three fields at once. He played so shallow that opponents often complained about a fifth infielder. Cool Papa Bell recalled, “It’s like he knew where the ball was going before it was hit. He would start running back while the pitcher was still winding up.” Teammate Elwood “Bingo” DeMoss credited him with, “an uncanny knowledge of judging fly balls.” At the plate and on the basepaths, he was a menace! In 1921, when he was with the St. Louis Giants, he led the Negro National League in doubles, triples, homeruns, stolen bases, and batting average! His three batting titles are tied for most in Negro Leagues history. His three Triple Crowns are the most in American professional baseball history! Charleston was always going to crack this starting lineup but which field to play him in was a touch choice, so I deferred to a legend. “The greatest MLB player I ever saw was Willie Mays. O’Neil often said, “But, the greatest baseball player I ever saw was Oscar Charleston.” Who am I to argue?

SIGNATURE MOMENT: In 1925, Oscar Charleston led the Eastern Colored League in batting average (.427), home runs (20), and RBIs (97) over the course of the 71-game season, which secured his second consecutive, and third career, Triple Crown.

OTHERS CONSIDERED: Willie Mays (Birmingham Barons: 1948), James “Cool Papa” Bell (St. Louis Stars: 1922 - 1929), Norman “Turkey” Stearnes (Detroit Stars: 1923 - 1931), Larry Doby (Newark Eagles: 1942 - 1944, 1946 - 1947)

“Batting second, the right fielder, #8, Willie Mays.”

RF | #8 | Willie Mays

Birmingham Black Barons (1948 - 1950)

Willie Mays, 1948

PAINTING BY: Graig Kreindler, from the collection of Jay Caldwell.

Nickname(s): “The Say Hey Kid”, “Buck”, “Willie the Wonder”, “The Amazin’ Mays”, “The Minneapolis Marvel”, “Cap”

Other Notable Teams: New York / San Francisco Giants (1951 - 1952, 1954 - 1972), New York Mets (1972 - 1973)

Awards: 2x National League MVP (MLB), 12x Gold Glove Award (MLB), 4x National League Homerun Leader (MLB), 4x National League Stolen Bases Leader (MLB), 1951 National League Rookie of the Year (MLB), 1954 National League Batting Champion (MLB), 1971 Roberto Clemente Award (MLB), San Francisco Giants #24 Retired, New York Mets #24 Retired, San Francisco Giants Wall of Fame, Major League Baseball All-Century Team, Major League Baseball All-Time Team, 1998 Sporting News “Baseball’s 100 Greatest Players” (#2), 2020 The Athletic “Baseball 100” (#1)

All-Star Nods: 24x All-Star (MLB)

Rings: 1 (1954 World Series Champion)

Hall of Fame: 1979 (USA), 2005 (Caribbean)

Bats: Right

Throws: Right

Batting Average: .301

Homeruns: 660

Runs Batted In: 1,909

Hits: 3,293

Stolen Bases: 339

Runs: 2,068

WHO’S HE? “I don’t know if they invented the term [five-tool player] to describe [Willie Mays],” Jayson Stark once wrote, “but he epitomized it like no one else.” Bill Rigney quipped that, “As a batter, his only weakness is a wild pitch.” One Dodgers’ executive referred to Mays’ glove as, “where triples go to die.” Gil Hodges remarked, "Wherever they hit it, [Mays is] there anyway." His roommate with the New York Giants, Monte Irvin, recalled, “He had those real big hands, great power and speed and would catch everything hit in his direction.” Like Irvin, Mays got his start in the Negro Leagues. As a high schooler in Birmingham, he was already turning heads. Buck O’Neil remembered,“The Birmingham Black Barons had this seventeen-year-old outfielder with the most spectacular arm I had ever seen.” The Decatur Daily noted his “bullet-true throwing arm” while the New Pittsburgh Courier admired the youngster’s “sharp fielding and clutch hitting.” When the Giants acquired Mays in 1950, the Birmingham News theorized that his future may be as a pitcher due to possessing “one of the most powerful throwing arms in baseball.” In 1951, he joined the team. After failing to record a hit in his first 23 Major League at-bats, Mays hit a home run over the left-field fence off Warren Spahn. Spahn later joked, “I’ll never forgive myself. We might have gotten rid of Willie forever if I’d only struck him out.” But Mays did indeed stay with the Giants, and the rest, as they say, is history.

WHY HIM? Monte Irvin consistently praised Mays as “the greatest player who ever lived.” Like many baseball fans, I tend to agree with that assessment. Similar to Oscar Charleston, Willie Mays was always going to crack this roster, it was just a matter of which position he would play. Given O’Neil’s previously mentioned endorsement of Charleston, putting Mays’ “bullet-true throwing arm” in right field is just an embarrassment of riches. Mays was so spectacular that Ted Williams would say, “They invented the All-Star Game for Willie Mays.” And given Mays’ 24 appearances, they might as well have! It’s more than the spectacular play, it’s the way those who saw “The Say Hey Kid” describe how fun he was to watch. Ted Kluszewski remarked, “I’m not sure what the hell charisma is, but I get the feeling it’s Willie Mays.” All I know is a generous helping of charisma in the outfield is exactly what this game needs.

SIGNATURE MOMENT: In the top of the 8th inning of Game 1 of the 1954 World Series, the score was tied 2 - 2, with two runners on base. Vic Wertz of the Cleveland Indians hit a shot to the outfield that it seemed would clear the bases and open up the game. Sprinting to deep center at the Polo Grounds, Willie Mays made an over-shoulder-grab at the warning track, spun around, hurled the ball to second, and prevented the runners from advancing. After “The Catch”, Mays’ New York Giants went on to win the game, and sweep the series.

OTHERS CONSIDERED: Hank Aaron (Indianapolis Clowns: 1952), Martín Dihigo (New York Cuban Stars: 1923 - 1927, 1930), Cristóbal Torriente (Chicago American Giants: 1919 - 1925), George “Mule” Suttles (Birmingham Black Barons: 1923 - 1925)

“Batting third, and playing catcher, #20, Josh Gibson.”

C | #20 | Josh Gibson

Homestead Grays (1930 - 1931, 1937 - 1940, 1942 - 1946)

Josh Gibson, 1931

PAINTING BY: Graig Kreindler, from the collection of Jay Caldwell.

Nickname(s): “The Black Babe Ruth”

Other Notable Teams: Pittsburgh Crawfords (1932 - 1936)

Awards: 10x National League Homerun Champion (NgL), 3x National League Batting Champion (NgL), 2x National League Triple Crown (NgL), Washington Nationals Ring of Honor, Pittsburgh Pirates Hall of Fame, FIRST TEAM: 1952 Pittsburgh Courier All-Time Negro League Team (C), 1998 Sporting News “Baseball’s 100 Greatest Players” (#18), 2020 The Athletic “Baseball 100” (#15)

All-Star Nods: 12x All-Star (NgL)

Rings: 8 (Negro League World Series Champion - 1943 & 1944, Negro National League Champion - 1931, 1935, 1936, 1937, 1938, 1940)

Hall of Fame: 1971 (Mexico), 1972 (USA)

Bats: Right

Throws: Right

Batting Average: .372

Homeruns: 174

Runs Batted In: 751

Hits: 838

Stolen Bases: 40

Runs: 612

WHO’S HE? When people spoke of Josh Gibson, they called him “The Black Babe Ruth”, but many who saw him attested that Babe Ruth was “The White Josh Gibson”. The imposing backstop, wielding a mammoth 40 ounce bat, was one of the most feared power-hitters in the history of professional baseball. “Josh was the greatest hitter I ever pitched to,” Satchel Paige said, “And I pitched to everybody … [Ted] Williams, [Joe] DiMaggio, [Stan] Musial, [Willie] Mays, [Mickey] Mantle. But none of them was as great as Josh.” Gibson’s Hall of Fame plaque credits him with nearly 800 homeruns. By some accounts, he hit a fair ball clear out of Yankee Stadium. His teammate Buck Leonard claimed he saw Gibson hit a ball to the upper deck of the Polo Grounds. “It must have gone 600 feet.” His manager with the Crawfords, Harold Tinker, said he “was built like sheet metal … If you ran into him, it was like you ran into a wall.” He was equally feared for his defense. Legendary catcher Roy Campanella said, “Everything I could do, Josh could do better.” Walter Johnson said, “He catches so easy, he might as well be in a rocking chair. Throws like a rifle.” Dizzy Dean called him, “one of the best catchers that ever caught a ball.” In a sad twist of fate, Josh Gibson died from a stroke at the age of 35, just a few months before Jackie Robinson made his Dodgers’ debut. "One of the things that was disappointing and disheartening to a lot of the black players at the time was that Jack was not the best player. The best was Josh Gibson,” Larry Doby once said, “I think that's one of the reasons why Josh died so early — he was heartbroken."

WHY HIM? On August 2, 1930, the Kansas City Monarchs hosted the Homestead Grays in the first-ever night game between professional baseball teams. In that game, Gibson made his first start. It’s always made sense to me that Josh Gibson debuted under the lights, because this was a man made for primetime. It’s so difficult to draw a modern comparison to Gibson because no catcher has ever hit like he did. Buck O’Neil said, “He had the power of Ruth and the hitting ability of Ted Williams.” By all accounts, he was a backstop built like Bo Jackson! Gibson is the most recent player in major American professional baseball to win consecutive batting Triple Crowns. The Major Leagues now recognize him as having both the highest single-season batting average (.466 in 1943) and the highest career one (.371). In the entire history of this sport, there is no batter I would want to see make a plate appearance more than Josh Gibson. He was the very first player I selected for this team.

SIGNATURE MOMENT: On September 12, 1943 in Washington, D.C., Josh Gibson hit a homerun off Philadelphia Stars’ pitcher Barney Brown. It was the 10th homerun that Gibson hit at Griffith Stadium, the home of the American League’s Washington Senators, in 38 games played there that season. By comparison in 1943, the entire Senators team hit only 9 homeruns at Griffith, in twice the games played!

OTHERS CONSIDERED: James Raleigh “Biz” Mackey (Hilldale Athletic Club: 1923 - 1931), Roy Campanella (Washington / Baltimore Elite Giants: 1937 - 1945), Louis “Top” Santop (Hilldale Athletic Club: 1918 - 1926)

“Batting clean-up, the first baseman, #32, Buck Leonard.”

1B | #32 | Walter “Buck” Leonard

Homestead Grays (1934 - 1950)

Buck Leonard, 1941

PAINTING BY: Graig Kreindler, from the collection of Jay Caldwell.

Nickname(s): “Buck”, “The Black Lou Gehrig”

Other Notable Teams:

Awards: 2x National League Batting Champion (NgL), 3x National League Homerun Champion (NgL), Washington Nationals Ring of Honor, Pittsburgh Pirates Hall of Fame, FIRST TEAM: 1952 Pittsburgh Courier All-Time Negro League Team (1B), 1998 Sporting News “Baseball’s 100 Greatest Players” (#47), 2020 The Athletic “Baseball 100” (#53)

All-Star Nods: 13x All-Star (NgL)

Rings: 8 (Negro League World Series Champion - 1943, 1944, & 1948, Negro National League Champion - 1937, 1938, 1940, 1941, 1949)

Hall of Fame: 1972 (USA)

Bats: Left

Throws: Left

Batting Average: .346

Homeruns: 97

Runs Batted In: 548

Hits: 748

Stolen Bases: 32

Runs: 549

WHO’S HE? Homestead Grays Manager Cumberland Posey called him, “one of the greatest clutch hitters in Negro baseball.” Buck O’Neil called him, “studious” and “one of the nicest guys I ever saw.” To Cool Papa Bell, he was “the best first baseman we had in the Negro Leagues.” But to pitchers in both the Negro Leagues and the Major Leagues, Buck Leonard was the latter half of the “Thunder Twins”, and the reason they could never pitch around Josh Gibson. In fact, Leon Day said on multiple occasions that, “I would rather pitch to Josh Gibson than to Buck.” Leonard had a way of turning fastballs into screaming line drives in a hurry. Pitcher Dave Barnhill remarked, “You could put a fastball in a shotgun and you couldn’t shoot it by him.” Roy Campanella agreed, praising Leonard’s “real quick bat”. Monte Irvin described him as “a dead-pull hitter … he feasted on fastballs. He hit a lot of homeruns too.” Defensively, Eddie Gottlieb considered Leonard “as smooth a first baseman as I ever saw.” A 1940 article in the New Pittsburgh Courier dubbed him, “a fielder without a flaw.” When Leonard was 45, he finally got a chance to play in the Majors when Bill Veeck offered him a spot on the St. Louis Browns. Leonard declined, knowing that fans would not be seeing him at his best, and fearing that his past-his-prime play would hurt the cause of integration. Leonard later said, "I only wish I could have played in the big leagues when I was young enough to show what I could do. When an offer was given to me to join up, I was too old, and I knew it."

WHY HIM? With all due respect to the “Home Run Twins” (Babe Ruth & Lou Gehrig) and the “M&M Boys” (Roger Maris & Mickey Mantle), the “Thunder Twins” may have been the greatest 3-4 combo in baseball history. Gibson hitting towering homeruns followed by Leonard striking ones that got out of a ballpark in a hurry. Pairing these two up in the heart of the lineup, just as the Grays once did, could not be passed up. According to one compilation, Leonard had a lifetime batting average of .355 against Negro Leaguers, and .382 against white Major Leaguers. Players used to say that, “sneaking a fastball past Buck Leonard was like trying to sneak sunrise past a rooster.” His prowess made him the perfect protection for Gibson in the rotation. While Gibson and Leonard would constantly switch spots dependent on the pitching matchup, it seems that both were at their best when Buck trailed Josh, and so that’s what I did here.

SIGNATURE MOMENT: On July 27, 1941, Buck Leonard stole the show as he led the East to an 8 - 3 victory in the East-West All-Star Game. Chester L. Washington wrote in the New Pittsburgh Courier, “Buck’s bristling single to right started the East’s stock scooting skyward when it scored Kimbro for the Oriental’s first tally. In the fourth again, it was Leonard’s 360-yard home run smash into the right field stands … which particularly put the game ‘on ice” for the East. And throughout, Buck’s brilliant big-league fielding was one of the afternoon’s highlights.” Washington would go on to name Leonard “the brightest star of the afternoon.”

OTHERS CONSIDERED: George “Mule” Suttles (Birmingham Black Barons: 1923 - 1925), Martín Dihigo (New York Cuban Stars: 1923 - 1927, 1930), Jud “Boojum” Wilson (Baltimore Black Sox: 1922 - 1930), Ben Taylor (Indianapolis ABCs: 1914 - 1918, 1920 - 1922)

“Batting fifth, the designated hitter, #5, Hank Aaron.”

DH | #24 | Henry “Hank” Aaron

Indianapolis Clowns (1952)

Hank Aaron, 1952

PAINTING BY: Graig Kreindler, from the collection of Jay Caldwell.

Nickname(s): “Hank”, “Hammerin’ Hank”, “Hammer”

Other Notable Teams: Milwaukee / Atlanta Braves (1954 - 1974), Milwaukee Brewers (1975 - 1976)

Awards: 1957 National League MVP (MLB), 4x National League Homerun Leader (MLB), 4x National League RBI Leader (MLB), 3x Gold Glove Award Winner (MLB), 2x National League Batting Champion (MLB), Atlanta Braves #44 Retired, Atlanta Braves Hall of Fame, Milwaukee Brewers Wall of Honor, Major League Baseball All-Century Team, 1998 Sporting News “Baseball’s 100 Greatest Players” (#5), 2020 The Athletic “Baseball 100” (#4)

All-Star Nods: 25x All-Star (MLB)

Rings: 1 (1957 MLB World Series Champion)

Hall of Fame: 1982 (USA)

Bats: Right

Throws: Right

Batting Average: .305

Homeruns: 755

Runs Batted In: 2,297

Hits: 3,771

Stolen Bases: 240

Runs: 2,174

WHO’S HE? “When I walked out on the field for my first game wearing a Clowns uniform,” Hank Aaron once said, “I felt like I was something special.” While playing semi-pro ball in Mobile, Alabama, Aaron caught the attention of the Indianapolis Clowns. The Baltimore Sun declared him to be, “the youngest player ever to break into the Negro League.” The first time Buck O’Neil saw Hank Aaron play was in an exhibition against the Kansas City Monarchs. O’Neil recalled sending out three different pitchers to fool the young Aaron, but he went 3-for-3 with a homerun. As Dodgers’ pitcher Claude Osteen would say years later, “Slapping a rattlesnake across the face with the back of your hand is safer than trying to fool Henry Aaron.” After that game, Clowns manager Buster Haywood was bragging about his new shortstop to which O’Neil replied, “Buster, when you come to Kansas City to play us again, Henry Aaron won’t be on your ballclub.” O’Neil was right. After only a few months in Indianapolis, the Milwaukee Braves purchased his contract for $10,000.00. “All Aaron was doing at the time of his sale”, the Alabama Tribune reported, “was leading the league in batting, runs, hits, doubles, runs batted in, home runs, and total bases. He was third in stolen bases.” Mickey Mantle said, “When he hits the ball - man, it’s like thunder.” Aaron’s thunderous bat debuted for the Braves in 1954, and within 20 years had him taking the crown as baseball’s “Homerun King”.

WHY HIM? Unlike many of the guys on this team, Hank Aaron got the opportunity to spend his career in the Majors. While he was barely in the Negro Leagues, he is still an important part of both the Negro Leagues’ story, and the story of integration in baseball. Even two decades after making the jump, Aaron was still threatened and jeered by fans on account of his race. He is a player I would have loved to see in his prime, and who belongs on this field. Boxing great Muhammad Ali once called him, “The only man I idolize more than myself.” Hank Aaron is the all-time leader in total bases and RBIs. He is famously second all-time in homeruns. Take away those 755 homeruns and the man would still be a member of the 3,000 Hit Club! Honestly, is there a better choice for DH in history than Hammerin’ Hank?!

SIGNATURE MOMENT: On April 8, 1974, at Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium, Hank Aaron took Dodgers’ pitcher Al Downing deep over the left-center wall. It was the 715th homerun of Aaron’s career, breaking a mark set by Babe Ruth that many baseball fans once thought unbreakable.

OTHERS CONSIDERED: Josh Gibson (Homestead Grays: 1930 - 1931, 1937 - 1940, 1942 - 1946), Oscar Charleston (Indianapolis ABCs: 1915 - 1918, 1920, 1922 - 1923), Willie Mays (Birmingham Black Barons: 1948), Buck Leonard (Homestead Grays: 1934 - 1950), Norman “Turkey” Stearnes (Detroit Stars: 1923 - 1931), Martín Dihigo (New York Cuban Stars: 1923 - 1927, 1930)

All paintings shown in the player profiles were painted by Graig Kreindler (www.graigkreindler.com, @graigkreindler), and are from the collection of Jay Caldwell. These paintings, and more, were on display at the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum (NLBM) in Kansas City, Missouri in 2020 for the celebration of the centennial of the founding of the Negro National League. They were displayed there again in 2022. The NLBM hopes to bring them back to KC on a permanent basis in the future.

Jay Caldwell initiated the project of honoring Negro Leagues players by bringing them to life through colored portraits for the Negro Leagues’ Centennial. He was fortunate when Graig Kreindler enthusiastically agreed to support this effort with his special artistic talent, and research on the colors of Negro Leagues uniforms. Graig and Jay continue to collaborate on projects to this day.

“Batting sixth, the left fielder, #6, Monte Irvin.”

LF | #6 | Monford “Monte” Irvin

Newark Eagles (1938 - 1943, 1945 - 1948)

Monte Irvin, 1939

PAINTING BY: Graig Kreindler, from the collection of Jay Caldwell.

Nickname(s): “Monte”, “Mr. Murder”, “Jimmy Nelson”

Other Notable Teams: New York Giants (1949 - 1955), Chicago Cubs (1956)

Awards: 3x National League Batting Champion (NgL), 2x National League Homerun Champion (NgL), 1951 National League RBIs Leader (MLB), San Francisco Giants #20 Retired, FIRST TEAM: 1952 Pittsburgh Courier All-Time Negro League Team (LF), 2020 The Athletic “Baseball 100” (#69)

All-Star Nods: 4x East-West All-Star (NgL), 1x All-Star (MLB)

Rings: 2 (1946 Negro League World Series Champion, 1954 MLB World Series Champion)

Hall of Fame: 1971 (Mexico), 1973 (USA)

Bats: Right

Throws: Right

Batting Average: .305

Homeruns: 140

Runs Batted In: 694

Hits: 1,076

Stolen Bases: 52

Runs: 580

WHO’S HE? In a 1976 interview, Monte Irvin expressed, “I lost ten or twelve good years. I came up at 31 years old … I have liked to come up when I was 18 or 19. I could have made it then.” Irvin made his Major League debut with the New York Giants in 1949 but many thought he’d be up much earlier. “Most of the black ballplayers thought Monte Irvin should have been the first black in the major leagues,” Cool Papa Bell said,”Monte was our best young ballplayer at the time.” Newark Eagles owner Effa Manley shared, “[Negro League owners] all agreed … he was the best qualified by temperament, character, ability, loyalty, morals, age, experience, and physique to represent us as the first black player to enter the white majors.” Many speculate that it was Effa Manley’s insistence on being fairly compensated for her players that caused Dodgers’ owner Branch Rickey to shift his focus away from Irvin and on to Jackie Robinson. Once Irvin finally arrived in the MLB, he made his presence felt. In 1951, he led the National League in RBIs and finished third in MVP voting, as the Giants won the pennant. Roy Campanella later shared, “Monte was the best all-around player I have ever seen. As great as he was in 1951, he was twice that good 10 years earlier in the Negro Leagues.” In 1954, Irvin helped lead the Giants to another pennant, and a World Series title, giving him the rare distinction of having won both a Negro Leagues World Series and an MLB one.

WHY HIM? “There’s few ballplayers who can do all five things - hit, field, run, throw, and think,” Effa Manley once said. But as she told The Daily Worker in 1947, “He has everything!” Cool Papa Bell said, “He could hit that long ball, he had a great arm, he could field, he could run. Yes, he could do everything.” Roberto Clemente considered Irvin his first baseball hero. “I used to wait in front of the ballpark just … so I could see him.” Willie Mays said, “He was all the things you’ve heard and more.” It seems, what Oscar Charleston was to the 1920s, Irvin was to the 1940s: a head-turning five-tool outfielder. How fortunate the New York Giants were to have a few years of Mays and Irvin in the same outfield. I may as well do the same!

SIGNATURE MOMENT: In Game 1 of the 1951 World Series, Monte Irvin, alongside Hank Thompson and Willie Mays, debuted as the first all-black outfield in the history of the Major Leagues. In the first inning of that same game, Monte Irvin stole home to score what would be the deciding run. While the Yankees would ultimately take the title, Monte Irvin batted .458 for the Giants over the course of the six-game series.

OTHERS CONSIDERED: Orestes "Minnie" Miñoso (New York Cubans: 1946 - 1948), Norman “Turkey” Stearnes (Detroit Stars: 1923 - 1931), John Preston “Pete” Hill (Cuban X-Giants: 1901 - 1902, 1905 - 1907), Martín Dihigo (New York Cuban Stars: 1923 - 1927, 1930)

“In the seventh spot, the shortstop, #18, Willie Wells.” [6]

SS | #18 | Willie “El Diablo” Wells

St. Louis Stars (1924 - 1931)

Willie Wells, 1925

PAINTING BY: Graig Kreindler, from the collection of Jay Caldwell.

Nickname(s): “El Diablo”, “The Devil”

Other Notable Teams: Chicago American Giants (1929, 1933- 1935), Newark Eagles (1936 - 1939, 1942, 1945)

Awards: 2x Cuban League MVP, 3x National League Batting Champion (NgL), 1930 National League Batting Champion (NNL), 1930 Triple Crown Winner (NgL), SECOND TEAM: 1952 Pittsburgh Courier All-Time Negro League Team (SS), ROLL OF HONOR: 1952 Pittsburgh Courier All-Time Negro League Team (2B), North Carolina Sports Hall of Fame (1974)

All-Star Nods: 10x All-Star (NgL)

Rings: 2 (Negro National League Champion - 1928 & 1930)

Hall of Fame: 1997 (USA)

Bats: Right

Throws: Right

Batting Average: .330

Homeruns: 140

Runs Batted In: 873

Hits: 1,292

Stolen Bases: 160

Runs: 932

WHO’S HE? In the late 1930s, fans marveled at the Newark Eagles’ “Million Dollar Infield” anchored by Willie Wells. Eagles’ owner Effa Manley called him, “the finest shortstop.” Teammate Monte Irvin said he was, “as good as Ozzie Smith and a better hitter.” Like Smith, Wells made his name in St. Louis. Fellow St. Louis Star, Cool Papa Bell called him, “the greatest shortstop in the world.” The St. Louis Star and Times reported, “The hard-hitting St. Louis infielder brought the fans to their feet as he scooped up grounders and rifled the throws to first,” and that, “Wells fielded with the grace of a major league star and packed power in his throwing arm.” Wells’ habit of making the spectacular look routine would later earn him the nickname of “El Diablo” when he played in the Mexican League. Monte Irvin described his play, saying, “He played a shallow shortstop, but had exceptional quickness and was expert at going back on line drives and pop flies. Wells also was one of the best curveball hitters I ever saw, and was a fast, aggressive baserunner. He was a clutch player who always came up with the big fielding play or key hit when it was needed.” Detroit TIgers’ Charlie Gehringer said, “he played the way all great players play – with everything he had." The New York World Telegram wrote that Wells was “stealing bases like Cool Papa Bell.” A clutch hitter, speedy around the bases, and acrobatic in the infield, Wells put the fear of “The Devil” in everyone he faced.

WHY HIM? By all accounts, Willie Wells was a triple threat. Buck O’Neil claimed, “Willie was a lifetime .364 hitter with a .410 average against major league competition in barnstorming games. He could hit to all fields, hit with power, bunt, and stretch singles into doubles and doubles into triples. But it was his glove that truly dazzled.” Cool Papa Bell said he “could cover ground better than [any shortstop I’ve seen].” The Wichita Beacon called him, “the fastest infielder in baseball.” It’s said that Willie Wells taught Jackie Robinson how to turn a double play! As incredible as Wells was, it’s the hustle, determination, and competitiveness that does it for me. It’s been said that if a player ever tried to take Wells out on a hard slide into second, he would pack pebbles in the fingers of his glove to make all future tags land a little harder. I couldn’t pass up a chance to see “El Diablo” up close.

SIGNATURE MOMENT: In a game against the Homestead Grays in 1939, Willie Wells stepped up to the plate wearing something unusual on his head - a coal miner’s helmet, sans the work light. It was Wells’ response to pitchers repeatedly throwing near his head. While there were prototypes before then, Wells was likely the first player to wear a batting helmet in a professional baseball game.

OTHERS CONSIDERED: John Henry “Pop” Lloyd (Lincoln Giants: 1911 - 1913, 1926 - 1930), Dick Lundy (Atlantic City Bacharach Giants: 1916 - 1918, 1920 - 1928), Pelayo Chacón (New York Cuban Stars: 1917 - 1931)

“Batting eighth, second baseman, #77, Pop Lloyd.” [7]

2B | #77 | John Henry “Pop” Lloyd

Lincoln Giants (1911 - 1913, 1926 - 1930)

Pop Lloyd, 1918 (shown here with the Brooklyn Royal Giants)

PAINTING BY: Graig Kreindler, from the collection of Jay Caldwell.

Nickname(s): “Pop”, “El Cuchara” (“The Spoon”)

Other Notable Teams: Philadelphia Giants (1907 - 1909), Chicago American Giants (1914 - 1917), Brooklyn Royal Giants (1918 - 1920), Bacharach Giants (1919, 1922, 1924 - 1925, 1932)

Awards: 2x Eastern Colored League Batting Champion, FIRST TEAM: 1952 Pittsburgh Courier All-Time Negro League Team (SS), Florida Sports Hall of Fame (1998), 2020 The Athletic “Baseball 100” (#25)

All-Star Nods [8]:

Rings: 1 (1923 Eastern Colored League Champions)

Hall of Fame: 1977 (USA)

Bats: Left

Throws: Right

Batting Average: .349

Homeruns: 16

Runs Batted In: 308

Hits: 569

Stolen Bases: 160

Runs: 932

WHO’S HE? John Henry “Pop” Lloyd and Honus Wagner are widely considered to be the finest shortstops of the Dead Ball Era. Connie Mack said, “You could put Wagner and Lloyd in a bag together and whichever one you pulled out, you couldn’t go wrong.” Many of the time called Lloyd “The Black Wagner”. Of this, Wagner said, “One day I had an opportunity to go see him play. After I saw him I felt honored that they should name such a great ball player after me.” When Babe Ruth was asked in a radio interview who he considered the greatest baseball player ever, he replied, “I’d pick John Henry Lloyd.” The Indianapolis Freeman described him as, “one man who is a wonder at fielding and hitting, also a fair base runner.” Described by the Hall of Fame as “a scientific hitter”, Lloyd seemed to be able to place the ball exactly where he wanted it. He also had a knack for being wherever the ball was hit. The way he scooped up dirt when he snagged ground balls caused Cuban fans to hail him as “El Cuchara” (“The Spoon”) His nickname of “Pop” came later, as a player-manager, for the way he mentored younger players. Bill Yancey said, “Pop Lloyd was the greatest player, the greatest manager, the greatest teacher. He had the ability and knowledge, and above all, patience. I did not know what baseball was until I played under him.”

WHY HIM? When it came to Wells and Lloyd, the question was never about their inclusion, but where they would play. I wrestled with this decision, going back and forth for a long time. Pop Lloyd is considered by many to be the finest shortstop in the history of the Negro Leagues, but then there’s others who say the same about Willie Wells. Wells actually received New Pittsburgh Courier poll votes at both positions, whereas Lloyd won the shortstop spot, and that seemed to settle things. But then, I ran across a New Pittsburgh Courier piece from 1927 where W. Rollo Smith wrote, “John Henry Lloyd stands out as the greatest second baseman of all time, and he is supreme at the bag yet. Of course, he made his greatest reputations as a shortstop, but I always thought second base was where he belonged.” Buck O’Neil wrote, “I saw Honus Wagner play. I saw Pop Lloyd play. … And if I had to pick a shortstop for my team, it would be Willie Wells.” Those two endorsements were enough for me to make the decision I did, and place Lloyd at the keystone bag.

SIGNATURE MOMENT: In 1924, when he was 40 years old, Pop Lloyd batted .444 and captured the Eastern Colored League batting title. At one point in that same season, he collected a base hit in 11 consecutive at-bats!

OTHERS CONSIDERED: Willie “El Diablo” Wells (St. Louis Stars: 1924 - 1931), Martín Dihigo (New York Cuban Stars: 1923 - 1927, 1930), Elwood “Bingo” DeMoss (Chicago American Giants: 1913 - 1914, 1917 - 1925)

“Batting last, the third baseman, #17, Judy Johnson.”

3B | #17 | William “Judy” Johnson

Hilldale Club (Daisies) (1921 - 1929, 1931 - 1932)

Judy Johnson, 1924

PAINTING BY: Graig Kreindler, from the collection of Jay Caldwell.

Nickname(s): “Judy”, “Mr. Sunshine”

Other Notable Teams: Homestead Grays (1929 - 1930, 1937), Pittsburgh Crawfords (1932 - 1938)

Awards: SECOND TEAM: 1952 Pittsburgh Courier All-Time Negro League Team (3B), Delaware’s Athlete of the Year (1976)

All-Star Nods: 2x East-West All-Star (NgL)

Rings: 5 (1925 Colored World Series Champion, 1923 Eastern Colored League Champion, Negro National League Champion - 1935, 1936, & 1937)

Hall of Fame: 1975 (USA)

Bats: Right

Throws: Right

Batting Average: .304

Homeruns: 25

Runs Batted In: 457

Hits: 809

Stolen Bases: 75

Runs: 467

WHO’S HE? As seemed to be the case with the greats of the Negro Leagues, Philadelphia Athletics manager Connie Mack told William “Judy” Johnson that if he were white, he could “write his own price”. Nicknamed Judy for his resemblance to “Judy” Gans, he was considered the best third baseman of the Negro Leagues in the 1920s. Arthur Ashe wrote, “Johnson was the standard by which other third basemen are measured.” The New Pittsburgh Courier reported he was, “one of the most finished ball players of the present day.” In 1924, when Johnson’s Hilldale Club lost the first Colored World Series to the Kansas City Monarchs, Johnson was widely praised as the most impressive player of the series for either roster. W. Rollo Wilson wrote, “He was the most consistent and timely hitter … and led the league in fielding his position and in the number of hits made.” Willie Wells praised Johnson’s “intelligence and finesse”. Teammate Ted Page called him the best third baseman he ever saw. “He had a powerful, accurate arm. He could do anything, come in for a ball, cut if off at the line, or range way over toward the shortstop hole.” Buck O’Neil called him, “a tremendous-hitting third baseman.” When the Majors integrated, Connie Mack hired the third baseman he once admired as a scout. However, Johnson lamented the Athletics ignoring his recommendations to sign Larry Doby, Hank Aaron, and Minnie Miñoso. “The A’s would still be playing in Philadelphia, because that would be all the outfield they’d needed,” Johnson later said.

WHY HIM? Choosing Judy Johnson over the prodigiously talented Ray Dandridge was the toughest call I made with this roster. Judy Johnson did not have the power of the rest of this line-up. He was known for his plate discipline, the ability to get a base hit when you needed it most, and the masterful way he manned the hot corner. More than anything, he was often praised for his leadership. He spent much of his career as a player-manager, and many lamented that he didn’t get the chance to manage in the Majors. When Johnson joined the All-Star-laden Pittsburgh Crawfords in the 1930s (with Josh Gibson, Oscar Charleston, Cool Papa Bell, and Satchel Paige), it was said that Johnson was the glue that held that historically great team together. Jimmie Crutchfield praised his “steadying influence.” His leadership, his defense, his clutch play, and the fact that he is a testament to the great Hilldale Athletic Club “Daisies” of the 1920s, made Johnson the right call for this roster.

SIGNATURE MOMENT: In Game 5 of the 1924 Colored World Series, Judy Johnson hit an inside-the-park home run, leading the Daisies to a critical win in the series. While Hilldale would ultimately fall to the Kansas City Monarchs in 10 games [9], Johnson’s team would return to defeat the Monarchs in the 1925 edition of the series.

OTHERS CONSIDERED: Ray “Hooks” Dandridge (Newark Eagles 1936 - 1938, 1942, 1944), Oliver “Ghost” Marcell (Bacharach Giants: 1918 - 1922, 1928), Orestes "Minnie" Miñoso (New York Cubans: 1946 - 1948), Jud “Boojum” Wilson (Baltimore Black Sox: 1922 - 1930)

Learn more about the Negro League pioneers who helped build the bridge that led to the integration of baseball, and society. Plan your visit to the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum today!

“Today’s starting pitcher for the All-Stars is #25, SATCHEL PAIGE!”

SP | #25 | Leroy “Satchel” Paige

Kansas City Monarchs (1940 - 1942, 1944 - 1947)

Satchel Paige, 1942

PAINTING BY: Graig Kreindler, from the collection of Jay Caldwell.

Nickname(s): “Satchel”

Other Notable Teams: Birmingham Black Barons (1927 - 1930), Pittsburgh Crawfords (1933 - 1934, 1936), Cleveland Indians (1948 - 1949), St. Louis Browns (1951 - 1953), Kansas City Athletics (1965)

Awards: Cleveland Guardians Hall of Fame, FIRST TEAM: 1952 Pittsburgh Courier All-Time Negro League Team (P), Tom Baird’s 1954 All-Time Kansas City Monarchs Team (P), 1998 Sporting News “Baseball’s 100 Greatest Players” (#19), 2020 The Athletic “Baseball 100” (#10)

All-Star Nods: 6x East-West All-Star (NgL), 2x All-Star (MLB)

Rings: 5 (1942 Negro World Series Champion, 1948 MLB World Series Champion, 1936 Negro National League Champion, Negro American League Champion - 1940 & 1941)

Hall of Fame: 1971 (USA)

Bats: Right

Throws: Right

Win-Loss Record: 125 - 82

Earned Run Average: 2.74

Strikeouts: 1,484

Complete Games: 96

Shutouts: 22

Saves: 44

WHO’S HE? “I got bloopers, loopers, and droppers. I got a jump ball, a bee ball, a screw ball, a wobbly ball, a whipsy-dipsy-do, a hurry-up ball, a nothin’ ball, and a bat dodger.” Leroy “Satchel” Paige had batters believing he had over two dozen pitches (he likely had an impressive seven or eight!) If you’ve heard of just one Negro Leaguer, it’s Satchel Paige; not only from those who faced him and played with him, but from the man himself. Nobody promoted Satchel Paige quite like Satchel Paige. Before we ever heard of Muhammad Ali, Paige was baseball’s version: a showman who backed up his mouth with his arm on the mound. “I never threw an illegal pitch,” Paige said, “The trouble is, once in a while, I toss one that ain’t ever been seen by this generation.”

Joe DiMaggio considered Paige the greatest pitcher he ever faced. Dizzy Dean and Grover Cleveland Alexander considered him among the best ever. Many say that Paige was routinely hurling the ball around 105 miles-per-hour. Biz Mackey said, “He threw it so hard that it disappeared before it reached the catcher’s mitt.” Monte Irvin praised his “great control”. There are many accounts of Paige being able to place a gum-wrapper anywhere on the plate and then perfectly throw the ball over the gum wrapper. Buck O’Neil said Paige always had the mental edge and, “was a master at messing with a man’s head.” Cumberland Posey praised his brilliance. The facts about Satchel Paige are too good to be true, and the legends are so specific, widespread, and unusual, that they are too good to be false. What is known is that after a Negro Leagues and barnstorming career where Paige threw in over 2,500 games (and likely won 80 percent of them), he got a chance in the Major Leagues at the age of 42. As a “rookie”, he went 6 - 1, had a 2.48 ERA, and helped lead the Cleveland Indians to their most recent World Series title. At age 45 and 46, he made the MLB All-Star Game. Then in 1959, at the age of 65, he became the oldest player in Major League Baseball history when he started a game for the Kansas City Athletics. In three innings pitched, he gave up no runs, and only one hit (a double by the great Carl Yastrzemski). The Kansas City Star reported, “It was almost unbelievable to watch Paige mow down the Boston hitters. He used fast balls, curves, and his famous hesitation pitch, which completely foiled the Red Sox batters.” In 1971, Satchel Paige became the very first player inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame on the basis of his Negro Leagues career.

WHY HIM? Many readers wondered why I left Satchel Paige off my Kansas City Monarchs’ fantasy roster. He is likely the greatest pitcher in the history of Kansas City. Heck, he’s arguably the greatest pitcher to ever throw a baseball! The truth is, that while Satchel will always be remembered as a Monarch, he meant even more to the Negro Leagues as a whole. As Buck O’Neil often put it, “Satchel Paige wasn’t just one franchise, he was a whole lot of franchises.” Paige not only played for a number of teams before the Monarchs, he played for a number of teams while he was with Kansas City! Owner J.L. Wilkinson routinely rented him out to other teams to help their gate. In the offseason, he was barnstorming with his own hand-picked crew of all-stars. In many ways, this team is more the Satchel Paige All-Stars than it is the East-West variety. In a match-up of Negro League legends, Satchel Paige absolutely has to be on the mound. And as a Monarchs fan, a face-off between Rogan and Paige is a dream scenario.

SIGNATURE MOMENT: In Game 2 of the 1942 Negro League World Series, with the Kansas City Monarchs leading the Homestead Grays 2 - 0, Satchel Paige gave up a two-out triple in the seventh. With Josh Gibson three batters away, Paige chose to intentionally walk the bases loaded to set up an epic showdown with Gibson. By some accounts, Paige told Gibson exactly what he was throwing him before each pitch. Gibson was caught looking on three straight fastballs as Paige closed out the inning. Walking off the field, Paige told Buck O’Neil, “Nobody hits Satchel’s fastball.” The Monarchs won the game, and the series.

OTHERS CONSIDERED: “Smokey Joe” Williams (Lincoln Giants: 1911 -1923), John Donaldson (All Nations: 1912 - 1918), Bill Foster (Chicago American Giants: 1923 - 1930, 1932 - 1935, 1937), “Cannonball” Dick Redding (Lincoln Giants: 1911 - 1916), Andrew “Rube” Foster (Chicago American Giants: 1911 - 1917), Leon Day (Newark Eagles: 1935 - 1939, 1941 - 1943, 1946)

“In the bullpen, #10, Leon Day, and #12, Smokey Joe Williams.” [10]

RP | #10 | Leon Day

Newark Eagles (1935 - 1939, 1941 - 1943, 1946)

Leon Day, 1939 (shown here with the Tiburones de Aguadilla of Puerto Rico’s Liga de Béisbol)

PAINTING BY: Graig Kreindler, from the collection of Jay Caldwell.

Other Notable Teams: Baltimore Elite Giants (1949 - 1950)

Awards: ROLL OF HONOR: 1952 Pittsburgh Courier All-Time Negro League Team (P)

All-Star Nods: 9x East-West All-Star (NgL)

Rings: 2 (1946 Negro League World Series Champion, 1949 Negro American League Champion)

Hall of Fame: 1995 (USA)

Bats: Right

Throws: Right

Win-Loss Record: 50 - 22

Earned Run Average: 3.58

Strikeouts: 432

Complete Games: 52

Shutouts: 9

Saves: 3

WHO’S HE? Nobody recorded more all-time strikeouts in the East-West All-Star Game or the Negro National League than Leon Day. “Day could throw as hard as anyone,” Larry Doby said, “I didn’t see anyone in the major leagues who was better than Leon Day.” The Hartford Courant called him the “top flinger of the Negro National League.” Monte Irvin said Day, “was as good or better than Bob Gibson.” Cumberland Posey wrote, “He is fast with a sharp curve, good control, and plenty of nerve.” The Afro-American reported in 1943, “Day has been rated one of the greatest pitchers colored baseball has ever produced and his blazing fast ball and sharp breaking curve made him a terror among batters in the Negro National League.” The article went on to praise Day’s versatility. Buck O’Neil wrote, “As good a pitcher as Leon was, he might have been better as a centerfielder.” When Day wasn’t on the mound, he regularly played elsewhere in the field. He was a great fielder, above-average hitter, and, according to Monte Irvin, “could run like a deer.” One report said Day, “ran 100 yards in 10 seconds in a baseball uniform.” A strikeout artist, Leon Day was one of the premier professional baseball pitchers of the 1940s. The Hall of Fame eventually agreed, inducting him in 1995. Fortunately, Day was able to learn the news of his induction less than a week before he passed.

WHY HIM? Leon Day was straight-up dominant! While Satchel Paige got all the press, in reality it was Leon Day and Hilton Smith who were the best of that decade. He had a fastball that was 90 - 95 miles per hour. He had a curveball that left batters cross-eyed. Many who saw both Day and Gibson pitch, claimed Day was every bit Bob Gibson’s equal, if not his superior. What’s most amazing to me is that Day managed to pack to so much power into such a small frame, and got so much movement on his pitches without any kind of wind-up. By all accounts, Day had an unorthodox sidearm delivery, and that’s something I’ve long dreamed of seeing.

SIGNATURE MOMENT: On July 24, 1942 in Baltimore, Leon Day pitched a complete game giving up one hit, one walk, one unearned run, and striking out a Negro National League record 18 batters! The Newark Eagles defeated the Baltimore Elite Giants 8 - 1.

CP | #12 | Joseph “Smokey Joe” Williams

Lincoln Giants (1911 - 1923)

Smokey Joe WIlliams, 1912

PAINTING BY: Graig Kreindler, from the collection of Jay Caldwell.

Nickname(s): “Smokey Joe”, “Cyclone Joe”

Other Notable Teams: San Antonio Black Bronchos (1907 - 1909), Homestead Grays (1925 - 1932)

Awards: FIRST TEAM: 1952 Pittsburgh Courier All-Time Negro League Team (P), 2020 The Athletic “Baseball 100” (#62)

All-Star Nods:

Rings:

Hall of Fame: 1999 (USA)

Bats: Right

Throws: Right

Win-Loss Record: 16 - 19

Earned Run Average: 3.51

Strikeouts: 201

Complete Games: 28

Shutouts: 2

Saves: 1

WHO’S HE? When the New Pittsburgh Courier released their famed All-Time Negro Leagues Team in 1952, Satchel Paige was the second-highest vote getter at the pitcher position. “Smokey Joe” (or “Cyclone Joe”) Williams beat him out for the top spot by a single vote. Both of his nicknames were drawn from his pitching speed. According to Paige, “Smokey Joe could throw harder than anyone.” The Akron Beacon Journal described him as a “smoke artist” and said he “whistled his fast ball like a 14-inch shell over the plate.” The Press of Atlantic City called Smokey Joe Williams, “one of the greatest colored pitchers to curve a baseball.” Ty Cobb thought Williams would have been a “sure 30-game winner in the Major Leagues.” Leland Giants owner Frank Leland famously said that, “If you ever witnessed the seed of a pebble in a windstorm that does not even come close to the speed of a Joe Williams fastball.” Williams once said, “Someone gave me a baseball at an early age, and it was my companion for a long time.” So long in fact, that Williams was a star of the dead-ball barnstorming era of the 1900s and 1910s, as well as in the organized Negro Leagues of the 1920s and 1930s.

WHY HIM? I’ll let Buck O’Neil take it from here. “Smokey Joe Williams went 41 - 3 pitching for the New York Lincoln Giants in 1914. Here’s another one: Smokey Joe Williams compiled a 20 - 7 record in exhibitions against major league competition. And another one: Smokey Joe Williams struck out twenty-seven Kansas City Monarchs when he pitched a twelve-inning one-hitter against them in 1930.” This is one of the greatest pitchers of the dead-ball era. It is very unlike Satchel Paige to have given anyone credit to any pitcher for being better than him in any way, but even he praised the speed of Smokey Joe. I have to believe Williams would make an incredible closer.

SIGNATURE MOMENT: On August 2, 1930, at Muehlebach Field in Kansas City, Smokey Joe Williams struck out 27 Kansas City Monarchs over the course of 12 shutout innings. Williams was 44 years old at the time. The Homestead Grays won the game 1 - 0.

OTHERS CONSIDERED FOR THE BULLPEN: Bill Foster (Chicago American Giants: 1923 - 1930, 1932 - 1935, 1937), John Donaldson (All Nations: 1912 - 1918), “Cannonball” Dick Redding (Lincoln Giants: 1911 - 1916), Andrew “Rube” Foster (Chicago American Giants: 1911 - 1917), Leroy Matlock (Pittsburgh Crawfords: 1933 - 1938), Don “Newk” Newcombe (Newark Eagles: 1944 - 1945), Dave Brown (Dallas Black Giants: 1917 -1918)

“On the bench, utility player, #65, Martín Dihigo.” [11]

UTIL | #65 | Martín Dihigo

New York Cuban Stars (1923 - 1927, 1930)

Martín Dihigo, 1937 (shown here with Las Águilas Cibaeñas de Santiago)

PAINTING BY: Graig Kreindler, from the collection of Jay Caldwell.

Nickname(s): “El Maestro”, “El Immortal”

Other Notable Teams: Homestead Grays (1927 - 1928), Hilldale Giants (1929 - 1931), New York Cubans (1935 - 1936, 1945)

Awards: 4x Cuban League MVP, 2x Eastern Colored League Homerun Champion, 1926 Eastern Colored League Batting Champion (NgL), 1929 Negro American League Runs Scored Leader, 1938 Mexican League Batting Champion, 1938 Mexican League Strikeouts Leader, FIRST TEAM: 1952 Pittsburgh Courier All-Time Negro League Team (UTIL INF), FIRST TEAM: 1952 Pittsburgh Courier All-Time Negro League Team (UTIL OF)

All-Star Nods: 2x East-West All-Star (NgL)

Rings:

Hall of Fame: 1951 (Cuba), 1964 (Mexico), 1977 (USA), 1997 (Venezuela) , 2008 (Dominican)

Bats: Switch

Throws: Right

Batting Average: .307

Homeruns: 68

Runs Batted In: 309

Hits: 436

Stolen Bases: 47

Earned Runs Average: 3.34

Strikeouts: 246

WHO’S HE? Whoever coined the term, “jack of all trades, master of none” never saw Martín Dihigo play. The Afro-American reported, “Dihigo … can play any position on the infield or outfield and his mound prowess also is a matter of records as he too is one of the best pitchers in Negro Baseball.” Johnny Mize said, “He was the only guy I ever saw who could play all nine positions, manage, run, and switch-hit.” Buck O’Neil called him, “The most versatile player in the history of baseball.” Roy Campanella said that he, “was one of the greatest I ever saw. He was a tremendous hitter, had great power, could hit for an average, everything.” Cumberland Posey claimed, Dihigo’s “gifts afield have never been approached by any man - black or white.” The Press of Atlantic City wrote that Dihigo hit “home runs by the wholesale.” In the Negro Leagues, he was feared; in his home nation of Cuba, he was celebrated. “It is difficult to explain what a great hero he was in Cuba,” Minnie Miñoso said, “Everywhere he went he was recognized and mobbed for autographs.” When he was done playing, Dihigo returned home and served as Minister of Sport under Fidel Castro. To this day, every baseball fan in Cuba knows the name Martín Dihigo. “If he’s not the greatest,” Buck Leonard said, “I don’t know who is. You take your [Babe] Ruths, [Ty] Cobbs, and [Joe] DiMaggios. Give me Dihigo.”

WHY HIM? Let’s be real - this spot always belonged to Dihigo. The man is in five different countries’ Hall of Fame! Remember that old cartoon where Bugs Bunny takes on a baseball team all by himself? That is exactly how I picture the great Martín Dihigo. How versatile was he? In a 1936 edition of The Daily Worker, writer Mark O’Hara asked a trio of Negro Leagues executives for their All-Star picks. All three listed Dihigo but each one assigned him to a different outfield position. In the famed 1952 New Pittsburgh Courier poll, he was named the starting utility infielder AND starting utility outfielder. On the Field of Legends inside the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City, Dihigo is actually the batter, because assigning him to just one defensive position would’ve been a disservice. In 2015, during Spring Training, Will Ferrell famously played all nine positions for ten different teams. Being the Swiss Army Knife that he was, my dream game would probably involve Dihigo playing each position for a single inning. That would be something to see!

SIGNATURE MOMENT: In 1938, while playing with El Águila de Veracruz, Martín Dihigo threw the first no-hitter in the history of the Mexican League. That season he went 18-2 with a 0.90 ERA and led the league in strikeouts. He also batted .387 on the season, winning the league’s batting title, and led the team to their second consecutive championship.

OTHERS CONSIDERED: Sam Bankhead (Pittsburgh Crawfords: 1935 - 1938), Emmett Bowman (Philadelphia Giants), Walter “Rev” Cannady (New York Black Yankees: 1933 - 1939)

“The Satchel Paige All-Stars are managed by Rube Foster“ [12]

MGR. | #81 | Andrew “Rube” Foster

Chicago American Giants, Player (1911 - 1917)

Chicago American Giants, Manager (1911 - 1926)

Rube Foster, 1916

PAINTING BY: Graig Kreindler, from the collection of Jay Caldwell.

Nickname(s): “Rube”, “Father of Black Baseball”, “Jock”

Other Notable Teams: Philadelphia Giants (1904 - 1906), Leland Giants (1907 - 1910)

Awards: Chicagoland Sports Hall of Fame, FIRST TEAM: 1952 Pittsburgh Courier All-Time Negro League Team (MGR)

All-Star Nods:

Rings: 4 (1926 Colored World Series Champion, Negro National League Champion - 1920, 1921, & 1922)

Hall of Fame: 1981 (USA)

Managerial Record: 336 - 195 - 11

Winning %: .633

WHO’S HE? “No ballplayer,” Buck O’Neil wrote, “not even Satchel [Paige] or Josh [Gibson], deserved to go in [the Hall of Fame] before Rube Foster, for all he did for our game.” Considered “The Father of Black Baseball”, it was Andrew “Rube” Foster who created the first organized Negro League. Prior to that, he was a dominant barnstorming pitcher who blew opponents away with his submarine delivery and his “fadeaway” pitch. Purportedly, he taught that same screwball to Christy Mathewson. Jewel Ens described him as, “a smart, cagey pitcher.” Honus Wagner said, “He was the smartest pitcher I have ever seen in all my years of baseball.” As a pitcher, he was player-manager, and later, just the manager for his Chicago American Giants. At the helm, Foster ran a tight ship, and taught his players the aggressive “keep the line moving” style that would come to define the Negro Leagues. Athletic defense, small ball, aggressive base-running, and bunting plays were the hallmarks of Foster’s teams. In one game in 1921, Foster’s Chicago American Giants overcame a 10-0 deficit by bunting 11 times in a row! The double steal, hit-and-run, and suicide squeeze were among his contributions to the game. The New Pittsburgh Courier called him “a master mind”, and said that his cunning likened him to Connie Mack and John McGraw. Remembered as a great pitcher and pioneering executive, Foster was also one of baseball’s all-time great skippers, and, per The Black Dispatch, “The most colorful figure in professional baseball.”

WHY HIM? Buck O’Neil wrote, “Ever since I saw Rube Foster use smoke signals to control a game, I had been fascinated by the job of the baseball manager.” Foster’s practice of using his pipe to signal his players would have been enough to make me want to see him. Then, the playing style comes into it. He used to make every player be able to bunt a ball into his strategically placed hat in order to make the team. Also, look at all the personalities on this roster! You have Satchel Paige, Josh Gibson, Oscar Charleston, Willie Wells; several on this team eventually became managers themselves. Rube Foster is the only guy that could reel in such a line-up and get the best out of them. It would be so much fun to watch!

SIGNATURE MOMENT: On February 13, 1920, Rube Foster, owner of the Chicago American Giants, gathered seven other Negro team owners at The Paseo YMCA in Kansas City, Missouri to form the Negro National League - the first organized professional baseball league for black teams.

OTHERS CONSIDERED: Cumberland Posey (Homestead Grays: 1918 - 1935), William “Dizzy” Dismukes (Dayton Marcos: 1918 - 1919), C.I. Taylor (Indianapolis ABCs: 1914 - 1921)

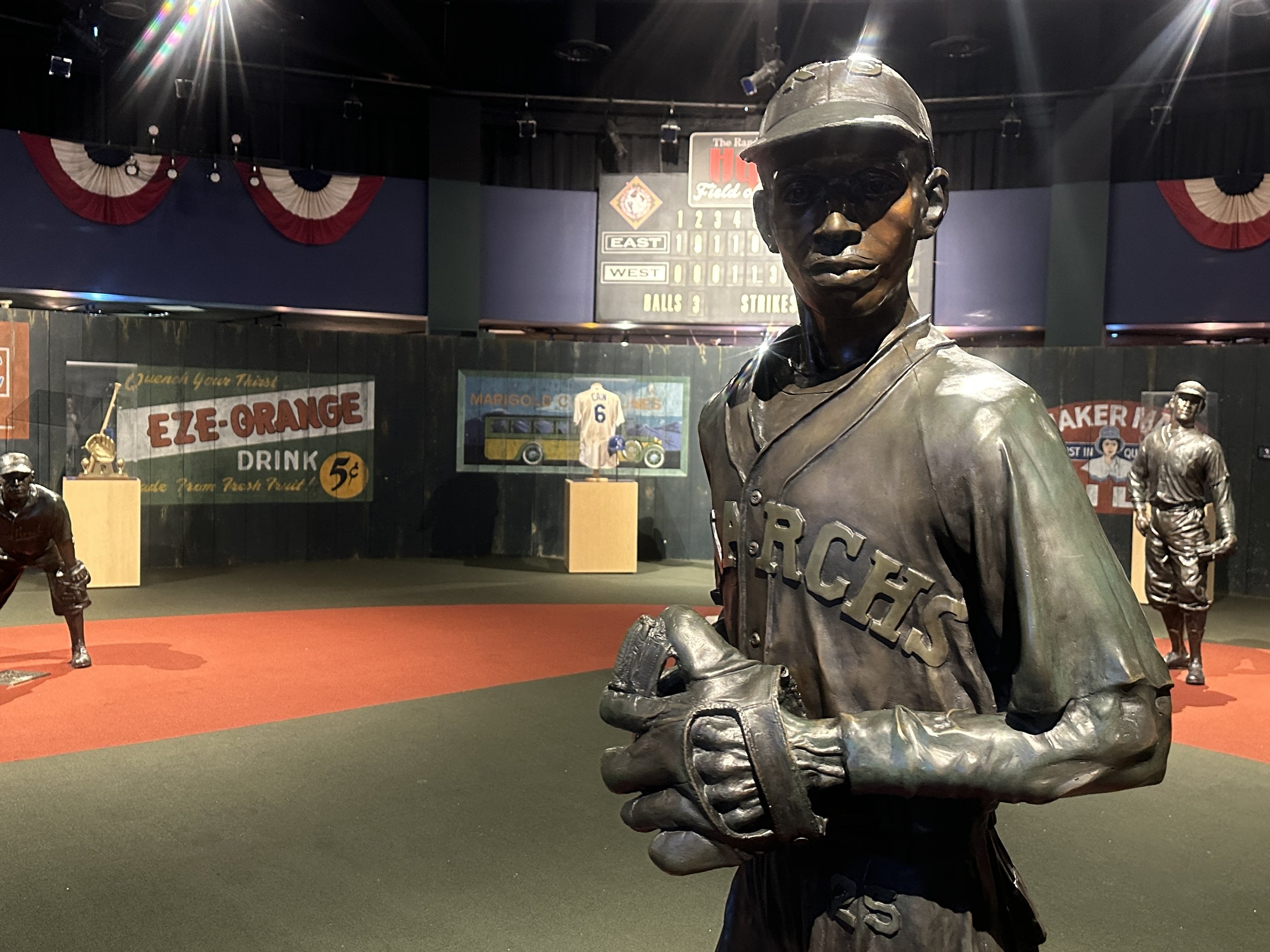

At the Negro League Baseball Museum’s Field of Legends, Satchel Paige takes the mound surrounded by many of these same teammates. PHOTO CREDIT - disKCovery

I had it all wrong! This wasn’t a game between the Kansas City Monarchs and the East-West All-Stars. These are the Satchel Paige All-Stars! The fireballer gathered up all of his barnstorming buddies, the very best of the Negro Leagues, and flew them into Kansas City on his plane (that bears this team name) in order to give the people a show.

And what a show it was! The buzz before the game evolved into an electricity that overtook Muehlebach and never dissipated. Each pitch was a masterpiece, with fastballs humming at high velocity and curveballs painting the corners of the plate. Changeups had batters whiffing at air, while palm-balls left others cross-eyed. The hits came, but runs were a rare commodity. Each time a team took the lead, the other side quickly had an answer.

When the 7th inning rolled around, Jay McShann hopped on the organ to lead the crowd in Take Me Out to the Ballgame. After nine, the score was deadlocked. As the game stretched into extras, the stakes grew higher. The crowd was on the edge of our seats, each pitch building suspense, each batter feeling the weight of the moment.

The Kansas City Monarchs invented night baseball, and it felt as if, with no end in sight, Wilkie might have to fire up the lights. The first two extra innings passed without a decision (although a deep fly from Gibson in the top of the 11th gave the home crowd a scare before Cool Papa Bell chased it down). Finally, in the bottom of the 12th, with two outs and the crowd holding its breath, a clutch single down the third base line from Elston Howard scored Jackie Robinson from second, sealing the win for the Monarchs.

As the players now retreat to their dugouts, I look around and realize the stadium is still full. Nobody wants to leave. I know what everyone else in the stands is feeling, because I feel it too, though none of us are fit to say the words. Monarchs’ first baseman Ernie Banks said it first, and he said it best,

“It’s a beautiful day for a ball game. Let’s play two!”

Those Pesky Endnotes That I Often Insist Upon

In 1969, three years after Ted Williams’ speech, the Baseball Writers Association of America (BBWA) formed a committee to nominate Negro Leagues players for the Baseball Hall of Fame. In 1971, the Baseball Hall of Fame created a special committee to elect Negro Leagues players to the Hall. In 1971, five years after Ted Williams’ remarks, Leroy “Satchel” Paige became the first player inducted into the Hall on the basis of his Negro Leagues career. Josh Gibson and Buck Leonard followed him in 1972. By 1977, just over a decade after Williams’ speech, nine Negro Leagues players were enshrined in Cooperstown, when none had been prior. CLICK HERE TO RESUME READING

When jersey number data for the team in question could not be found, or was unavailable, I assigned the number to the player. While I could not find any information on Oscar Charleston’s number as a player, he did wear #40 when he managed the Indianapolis Clowns. CLICK HERE TO RESUME READING

In May 2024, Major League Baseball took a momentous step forward and incorporated the stats of select Negro Leagues (1920 - 1948) into the MLB record books. The stats shown here are from Baseball Reference. They may be stats from playing in the Major Leagues, playing in the Negro Leagues, or a combination thereof. Regardless, these are BIG LEAGUE stats. Keep in mind, that these numbers may not tell the whole story and may be incomplete, as statistics were not consistently kept for all games these players played in - especially in international fixtures, exhibition games, and barnstorming play which was incredibly common in the 1930s. In some instances, I incorporated Negro Leagues, barnstorming, and Latin American league stats from Seamheads and Retrosheet into the player description write-ups. The work that the likes of Seamheads and Retrosheet have done to compile old box scores, and derive statistics from them, is beyond praiseworthy. CLICK HERE TO RESUME READING

A name being highlighted in green denotes that they are enshrined in the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York. The green highlight is only used on the first instance of a name in each player profile, as well as in the “Others Considered” bracket. CLICK HERE TO RESUME READING

In baseball, the five tools are the ability to field, throw, run, hit for average, and hit for power. A “five-tool player” is the rare athlete who excels in all of these areas. CLICK HERE TO RESUME READING

Jersey number data for Wells’ time with the St. Louis Stars was unavailable. Willie Wells wore #18 when he played for the Memphis Red Sox at the end of his career. His son, Willie Wells, Jr. was on that same roster and wore #17. CLICK HERE TO RESUME READING

Having no jersey number data available for Pop Lloyd throughout his career, this is a fabricated number. Pop Lloyd was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1977, so I chose #77. CLICK HERE TO RESUME READING

The East-West All-Star Game was established in 1933, the same year as Major League Baseball’s All-Star Game. It stands to reason that an excellent player of Lloyd’s caliber would have had All-Star nods if the game had existed during his prime. This will be worth considering for any other greats in this article whose tenure or career largely predates 1933. CLICK HERE TO RESUME READING

The Colored World Series was a best-of-nine series. The inaugural edition went to 10 games because Game 3 was ruled a tie after thirteen innings, on account of it being too dark out to continue the game. CLICK HERE TO RESUME READING

There was no jersey number data available for Smokey Joe Williams. This is a fabricated number. In his 2001 book The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract, baseball historian and statistician Bill James ranked Smokey Joe Williams at the 12th best pitcher of all time, so I chose #12. CLICK HERE TO RESUME READING

While jersey number data for his time with the Cuban Stars was unavailable, a 1945 Caramelo Deportivo baseball card depicts Martín Dihigo as #65. CLICK HERE TO RESUME READING

Jersey number data for Rube Foster was unavailable. Given Foster’s era, he likely never wore a number as a player. As a manager, he often dressed smartly, donning a suit, tie, and hat. This is a fabricated number. In 1981, Rube Foster was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame, hence the #81. CLICK HERE TO RESUME READING

Who did I leave off this roster that was included? Who would play in your perfect game? As always, let me hear it in the comments!