Fantasy Baseball - Part 1

I might never see a perfect game with my own two eyes, so I may as well write one. PHOTO CREDIT - disKCovery

Published March 27, 2025

“God, I love baseball.”

There’s no other way to say it. Roy Hobbs may have said it first, but he also said it best.

I love baseball. It’s not a trivial love, like the one reserved for ice cream, or any other fleeting source of joy. No, my love for this game runs much deeper than that. It’s so much more than a game. Baseball is an emotion. It’s a feeling. It’s a sensation that that has a way of reaching into the very depths of my soul. Like “Crash” Davis, I too “believe in the hangin’ curveball” and that, “there ought to be a constitutional amendment outlawing Astroturf.” (Though I must admit, our opinions on the DH do differ. But, that’s a conversation for another day.)

“And the only church that truly feeds the soul, day-in day-out, is the Church of Baseball.”

The scent of fresh-cut grass. The crack of a bat. The satisfying thud of a ball finding leather. A refreshing pint of beer after a hot dog or two. Yes, baseball has its smells. It has its sounds. It has a taste. And as Stanley Ross revealed to us all in his second stint with the Milwaukee Brewers - it even has a song.

When news breaks every year of pitchers and catchers reporting to Spring Training, it is the first note of a melody; a resilient whisper that braves the cold stillness of winter to announce to all willing to listen that summer will soon be here. As Billy Beane (or at least Aaron Sorkin’s version of the longtime Athletics’ GM) put it, “It’s hard not to be romantic about baseball.”

Now, I’m not about to claim that my affection for baseball even compares to the love I have for family or friends, but there is something to be said about the moments it creates and the bonds it can foster. Baseball’s been an immeasurable source of memories with the people I care about most.

For as long as I can remember, this game - once considered “America’s Pastime” - has been a constant source of joy. It’s always been more than a sport. It’s a part of me; a part of many of us. It’s a phenomenon that connects this generation with the ones who came before.

“The one constant through all the years … has been baseball.”

Even reading those words, I get goosebumps, hearing them in the familiar timbre of James Earl Jones. “America has rolled by like an army of steamrollers. It’s been erased like a blackboard, rebuilt, and erased again. But baseball, has marked the time. This field, this game - it’s a part of our past … It reminds us of all that once was good, and it could be again.”

And when this time of year rolls around? I can’t help but be reminded of all that once was good in Kansas City baseball.

It’s easy for me to be excited after last year’s Royals’ postseason run. I reminisce about the incredible teams of 2014 - 2015 that I was fortunate to witness. I watch highlights of the American League powerhouse of the 70s and 80s whose exploits were just before my time. And as for the Athletics who preceded them? Well, there’s not much greatness to remember there.

But mostly, I think about this city’s original sports dynasty. I think about the perennial contenders that I have no way to go back and watch — the Kansas City Monarchs. I dream about what it must have been like to watch them play. Imagining 18th & Vine in its heyday, when baseball, barbecue, and jazz all intersected in this place untouched by Prohibition — that’s my Roman Empire.

“And there used to be a ballpark where the field was warm and green,

And the people played their crazy game with a joy I’d never seen,

And the air was such a wonder from the hot dogs and the beer,

Yes, there used to be a ballpark right here.”

Every now and then, I visit Monarch Plaza, where Muehlebach Field (later Municipal Stadium) once stood, and I think about the legends who played there. Almost weekly, I drive by the Negro Leagues murals at the old Paseo YMCA. I’ll occasionally pull over and gaze at the KC Monarchs’ greats painted on the wall, wishing I could see these men emerge from a cornfield and play one last game.

When I’m there, it’s impossible not to get swept up in the legacy of these legends. The spirit of the Monarchs feels ever-present in that place, demanding both reverence and awe. And while I may never get to witness their greatness firsthand, there is something I can do. I can bring them back, not by some mystical ritual, but through the power of prose.

I may never attend a perfect game, but with my words, I can craft my own.

I can build my dream roster of Kansas City Monarchs’ greats, handpicking my favorite players from across all eras. Whether they were on the team for a season or a decade, I can bring together the best Monarchs, in their primes, to run onto the diamond one last time. It would be my own “Muehlebach Field of Dreams”.

Of course, I will need players for all nine positions on the field. In the spirit of the modern game, I’ll add a designated hitter, a utility player, a relief pitcher, and a closer to round things out. Last of all, this team will need a manager, bringing the roster to fourteen.

In my mind, history and imagination meet. The players of yesterday and the game as I know it today come together. In this place, outside of time, the best traditions of Kansas City baseball all melt into one another, creating a memory without blemish.

I close my eyes, and the perfect game begins to take shape. I see it clearly. One-by-one, the Monarchs emerge from the dugout, and Muehlebach Field comes back to life.

Part I: Your Kansas City Monarchs

“As much as I liked Saturday nights, I think I liked Sundays even better. They held church services an hour earlier when the Monarchs were in town, and the thousands of fans we got - both black and white - were dressed so nicely and seemed so excited that you couldn’t help but feel you were part of something special.”

It’s a gorgeous Sunday afternoon at Muehlebach Field. The sun hangs just right. It’s 70 degrees out with not even a hint of wind. Everything about this day feels like it was made for baseball. I stroll through the gates at 22nd and Garfield with a newspaper-wrapped portion of Henry Perry’s smoked mutton and pork ribs in hand. Already, I’m on the lookout for a hawker who will sell me a 10 cent bottle of beer.

The stadium is packed to the brim with fans who are dressed in their Sunday best. Among the well-dressed is Kansas City Monarchs’ owner J.L. Wilkinson. Before injuries derailed his career, the Hall of Fame Executive was once a promising pitcher in his own right. I’d have to believe there would be enough left in his wrist on this day to throw out a ceremonial first pitch. Just a chance for me to see Wilkie in the flesh and give him a well-deserved round of applause would be enough.

Though I can’t know for certain if the National Anthem was played before Negro Leagues games, I like to imagine that the neighborhood’s own Charlie “Bird” Parker, the greatest saxophonist who ever lived, would be there to kick things off. The Monarchs stand at attention in their cream-colored, pinstriped uniforms from 1945 [1]. The giant red, block “KC” on the players’ chests is easily legible, even from the uppermost rows.

As the final soulful note of Parker’s anthem fades, the ballpark’s speakers crackle to life, announcing the Monarchs as they take the field [2].

BUT FIRST, A NOTE FROM THE WRITER: For as much as I love the Kansas City Monarchs, and revere the Negro Leagues, I equally appall the inhumane realities of that time which made a separate league necessary. As many do, I wish these leagues did not have to exist. It is not the intention of this piece to glamourize the atrocity of segregation. Instead, it is to recognize the greatness of these Kansas City sports legends, and to think about how special it would have been to see these men play. While I paint a picture that puts the stadium in the 1930s, please remember that this is a game outside of time. The beauty of a fantasy, is that I can picture both a game that is perfect, and societal attitudes that are as well. In regard to the latter, we have come so far, but we still have a long way to go.

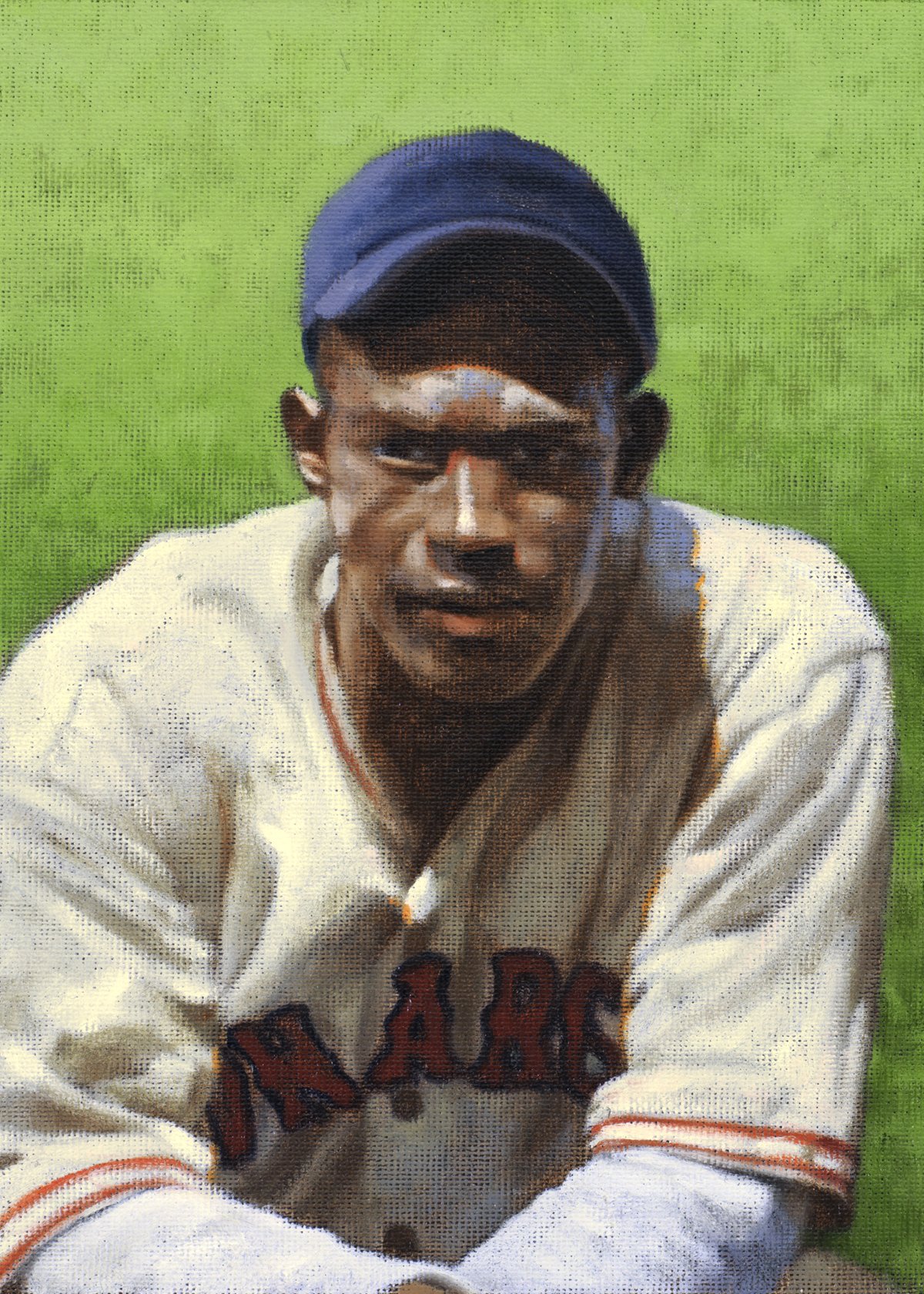

“At catcher, #12, ELSTON HOWARD!”

C | #12 | Elston Howard

Kansas City Monarchs (1948 - 1950)

Elston Howard, 1948

PAINTING BY: Graig Kreindler, from the collection of Jay Caldwell.

Nickname(s): “Ellie”

Other Notable Teams: New York Yankees (1955 - 1967), Boston Red Sox (1967 - 1968)

Awards: 1963 American League MVP (MLB), 2x Gold Glove (MLB), No. 32 Retired (Yankees)

All-Star Nods: 12x All-Star (MLB)

Rings: 6 (MLB World Series Champion - 1956, 1958, 1961, 1962, 1977, & 1978)

Hall of Fame:

Bats: Right Throws: Right

Batting Average: .274 [3]

Homeruns: 168

Runs Batted In: 775

Hits: 1,491

Stolen Bases: 50

Runs: 635

ONCE UPON A TIME: When he was 19, Elston Howard had his pick of Big Ten college football scholarship offers. He turned them all down, choosing instead to play for Buck O’Neil’s Monarchs for $500 per month. Howard’s first season in Kansas City, Mickey Taborn was established as the team’s backstop, but O’Neil recalled that, “when I saw Elston hit one over the scoreboard at Municipal Stadium in his first game, I found a place for him in the outfield.” Later, O’Neil would move Howard to the catcher position where he excelled.

After a tour of duty in the Korean War, Elston Howard found himself in a similar position in 1955. When he arrived in the Bronx as the first black player in Yankees’ history, Yogi Berra [4] was behind home plate. Initially, Howard had to compete with the likes of Mickey Mantle, Hank Bauer, and Enos Slaughter for playing time in the outfield. On top of that, Howard had to fight the prejudice that many black ballplayers faced in the Majors at that time. His wife Arlene would later recall that, “When Elston came [to the Yankees], what he had to go through is somewhat the same as what Jackie [Robinson] had to face.” Eventually, Howard became the team’s everyday catcher. He is largely remembered for being the first black player to win the American League MVP, which he did in 1963. In 1969, when his playing days were over, he followed in the footsteps of his former skipper Buck O’Neil by becoming the first black coach in American League history.

WHY THIS GUY? This was one of the easiest choices on the roster. While Howard was primarily an outfielder with the Monarchs, he is remembered as a great catcher. While with the New York Yankees, he won back-to-back Gold Gloves and an American League MVP. He set single-season records for putouts and chances offered. His lifetime fielding percentage of .993 was a Major League record for catchers until 1973. As a guy who was known for his gentlemanly demeanor and astute baseball mind, several believe Elston Howard was unfairly denied the chance to be the MLB’s first black manager. I am among several fans who believes that Elston Howard is long overdue for inclusion among baseball’s immortals in Cooperstown.

FUN FACT: In 1967, Elston Howard introduced “Elston Howard’s On-Deck Bat Weight”, more commonly known today as the “batting donut”. Howard’s hometown St. Louis Cardinals were the first to buy the device for their ball club. Still in use in the Major Leagues today, Howard never made the money he should have off the donut because he lacked the resources to take legal action against copycats and imitators.

OTHERS CONSIDERED: Frank Duncan (Kansas City Monarchs: 1921 - 1930, 1937 - 1938, 1941 - 1945), Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe (Kansas City Monarchs: 1945), Oscar “Heavy” Johnson (Kansas City Monarchs: 1922 - 1924)

“The first baseman, #28, ERNIE BANKS!”

1B | #28 | Ernie Banks

Kansas City Monarchs (1950, 1953)

Ernie Banks, 1953

PAINTING BY: Graig Kreindler, from the collection of Jay Caldwell.

Nickname(s): “Mr. Cub”, “Mr. Sunshine”

Other Notable Teams: Chicago Cubs (1953 - 1971)

Awards: 2x National League MVP (MLB), 1960 Gold Glove (MLB), 2x National League Homerun Leader (MLB), 2x National League RBI Leader (MLB), No. 14 Retired (Cubs), Chicago Cubs Hall of Fame, Major League Baseball All-Century Team, Presidential Medal of Freedom (2013), 1998 Sporting News “Baseball’s 100 Greatest Players” (#38), 2020 The Athletic “Baseball 100” (#65)

All-Star Nods: 1x East-West All-Star (NAL), 14x All-Star (MLB)

Rings: 1 (1953 Negro American League Champion)

Hall of Fame: 1977 (USA)

Bats: Right Throws: Right

Batting Average: .274

Homeruns: 512

Runs Batted In: 1,636

Hits: 2,583

Stolen Bases: 10

Runs: 1,305

ONCE UPON A TIME: In 1949, “Cool Papa” Bell was managing the Monarchs’ B Team. On a road trip, he was awestruck by the play of the 17 year old shortstop for the semi-pro San Antonio Black Shepherders. Bell’s rave reviews were enough for Buck O’Neil to drive to Dallas that winter and sign Ernie Banks to a contract, without ever seeing him play.

Joining the Monarchs for the 1950 season, Banks lived at the historic Street Hotel (18th & Paseo) where he roomed with Elston Howard. The signing of Jackie Robinson by the Dodgers three years prior, made the MLB a possibility for Banks and Howard, so they made a deal: whoever got to the Majors first would have to call the other and tell them what it was like. Banks left the team in 1951 to serve in Germany during the Korean War. When he returned in 1953, he had a stellar season and was named the starting shortstop in the Negro Leagues East-West All-Star Game at Comiskey Park. After hitting a walk-off homer in the game, Banks caught the attention of the cross-town Cubs, and beat Howard to the Majors.

Banks would later recall that he was hesitant to leave for the “Friendly Confines” of Wrigley Field. In a 2012 interview, Banks said, “I wanted to stay with the Monarchs … They were like my family … Playing for the Kansas City Monarchs was like my school, my learning, my world. It was my whole life.” But the man who would become known as “Mr. Cub” did join Chicago that season, and the rest as they say is history. In 1960, he won the first Gold Glove in Cubs’ history. Beloved in Chicago for his infectious smile and phenomenal play, Banks was the first player to win back-to-back National League MVPs, and was also the first Cubs player to have his jersey number retired by the team.

WHY THIS GUY? Ernie Banks will always be remembered as a transformative shortstop, as he should be! It’s the position he loved to play. It’s the position he played with the Monarchs, and where he began his career with the Cubs. He was an exceptional fielder and had power that had never been seen at the position prior. In 1955, he hit a then MLB record five grand slams in a single season. Banks recorded five 40 homerun seasons before any other shortstop in MLB history even had one! However, when all was said and done, Banks actually played more Major League games at first base than he did at shortstop. He led the league in putouts five times, and had just as many MLB All-Star nods at first base as he did at shortstop. When you look at the history of the Kansas City Monarchs, you begin to realize how much incredible talent there was at the shortstop position. Playing Ernie Banks at first base seemed like the best way to get him on the field.

MONARCHS MOMENT: In 1953, Ernie Banks drove in 47 runs in 46 games played. His exceptional glove and .347 batting average earned him a spot as the West’s starting shortstop in the East-West All-Star Game.

OTHERS CONSIDERED: John Jordan “Buck” O’Neil (Kansas City Monarchs: 1938 - 1943, 1946 - 1955), George “Tank” Carr (Kansas City Monarchs: 1920 - 1922), Lemuel Hawkins (Kansas City Monarchs: 1921 - 1927)

“Playing second base, #5 JACKIE ROBINSON!”

2B | #5 | Jackie Robinson

Kansas City Monarchs (1945)

Jackie Robinson, 1945

PAINTING BY: Graig Kreindler, from the collection of Jay Caldwell.

Nickname(s): “Jackie the Robber”

Other Notable Teams: Brooklyn Dodgers (1947 - 1956)

Awards: 1947 Rookie of the Year (MLB), 1949 National League MVP (MLB), 1949 National League Batting Champion (MLB), 2x National League Stolen Base Leader (MLB), No. 42 Retired (Dodgers), No. 42 Retired (MLB), FIRST TEAM: 1952 Pittsburgh Courier All-Time Negro League Team (2B), Major League Baseball All-Century Team, 1998 Sporting News “Baseball’s 100 Greatest Players” (#44), 2020 The Athletic “Baseball 100” (#42)

All-Star Nods: 1x East-West All-Star (NgL), 6x All-Star (MLB)

Rings: 1 (1955 MLB World Series Champion)

Hall of Fame: 1962 (USA)

Bats: Right Throws: Right

Batting Average: .313

Homeruns: 141

Runs Batted In: 761

Hits: 1,563

Stolen Bases: 200

Runs: 972

ONCE UPON A TIME: Monarchs’ pitcher Hilton Smith often recounted an incident with his roommate, Jackie Robinson, at a filling station in Muskogee, Oklahoma. The team made a routine stop at a station they frequented. Robinson headed towards the restroom but was barred from using it due to his skin color. Calmly, Robinson told the station’s owner, “Take the hose out of the tank.” Unable to pass on a 100 gallon sale, the owner relented. Buck O’Neil would later explain on the Late Show with David Letterman, “From that day on, we never got gas at a station where we couldn’t go to the restroom. We never played in a town that they didn’t have a place for us to stay and to eat.”

Smith first saw Robinson play in 1942 at Fort Hood, while Robinson was in the Army. After Robinson was discharged in 1944, Smith encouraged him to try out for the Monarchs, and convinced J.L. Wilkinson to sign him for the 1945 season. Already famous as a UCLA All-American running back, Robinson drew significant attention. On Opening Day that year, The Kansas City Star noted that “the rookie sensation of Negro baseball … [known for football] rapidly is developing into an even greater baseball prospect.” In his first league game, Robinson had a hit, a run, an RBI, and turned a double play. That summer, The Kansas City Star reported, he was “still playing sensationally at shortstop and continues to pound the ball for extra bases.” The rookie played well enough to be selected for the East-West All-Star Game.

Despite his success, Robinson was unhappy in the Negro Leagues.. It was a contrast to the structure he’d known in the Army and at UCLA. He once called it “a miserable way to make a buck.” Smith urged Robinson to stick with it, convinced of his future in baseball. At the end of the 1945 season, Brooklyn Dodgers owner Branch Rickey signed Robinson to the Montreal Royals. Rickey controversially refused to pay the Monarchs for Robinson’s contract, believing the Negro Leagues deserved no respect from “organized baseball.”

What happened next is well-known, because the story of Jackie Robinson transcends baseball. On April 15, 1947, Jackie Robinson made his debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers, breaking through baseball’s self-imposed color line and jumpstarting the modern Civil Rights movement. Today, Robinson’s #42 is retired across Major League Baseball (MLB), but how different things might’ve been if Hilton Smith had not encouraged him to put on #5 in Kansas City.

WHY THIS GUY? While Jackie Robinson started at shortstop for the Monarchs in 1945, former Monarchs’ second baseman Newt Allen recognized Robinson’s more natural fit. He told Wilkinson before the season, “[Robinson’s] a very smart ballplayer, but he can’t play shortstop - he can’t throw from the hole. Try him at second base.” Often lost in his status as a trailblazer is that Robinson is one of the greatest all-around second basemen in history. I would give anything to see his speed and athleticism on the base paths with my own eyes. Having Robinson man the keystone for the Monarchs was something I couldn’t pass up.

MONARCHS MOMENT: On July 7, 1945, Jackie Robinson recorded the only multi-homerun game of his Monarchs’ career, taking the Birmingham Black Barons deep twice. The following day, in a game reportedly played in ankle-deep mud in Kansas City, Robinson went 3-for-5 at the plate, with two doubles, driving in three runs and brought his season average to .500! He also turned a pair of double plays and recorded six assists. The Monarchs would beat the Black Barons 9 - 1.

OTHERS CONSIDERED: Newt Allen (Kansas City Monarchs: 1923 - 1944), Willie Wells (Kansas City Monarchs: 1932), Bonnie “El Grillo” Serrell (Kansas City Monarchs: 1942 - 1945)

“The shortstop, #7, DOBIE MOORE!” [5]

SS | #7 | Walter “Dobie” Moore

Kansas City Monarchs (1920 - 1926)

Dobie Moore, 1916

(shown here with the 25th Infantry Wreckers)

PAINTING BY: Graig Kreindler, from the collection of Jay Caldwell.

Nickname(s): “Dobie”, “The Black Cat”, “Freckles”, “Scoop”

Other Notable Teams: 25th Infantry Wreckers (1916 - 1920)

Awards: 1918 Honolulu Star-Bulletin Service League All-Star (3B), 1920 Kansas City Sun All-Negro Leagues Team, 1924 National League Batting Champion (NgL), 1924 National League Homerun Champion (NgL), ROLL OF HONOR: 1952 Pittsburgh Courier All-Time Negro League Team (SS), Tom Baird’s 1954 All-Time Kansas City Monarchs Team (SS)

All-Star Nods [6]:

Rings: 2 (1924 Colored World Series Champion, 1923 Negro National League Champion)

Hall of Fame:

Bats: Right Throws: Right

Batting Average: .350

Homeruns: 34

Runs Batted In: 386

Hits: 637

Stolen Bases: 66

Runs: 371

ONCE UPON A TIME: Prior to joining the newly-formed Kansas City Monarchs in 1920, Walter “Dobie” Moore was enlisted in the U.S. Army and impressed as an infielder for the famed 25th Infantry Wreckers. In an exhibition series against a team of barnstorming Major Leaguers in 1919, Moore wowed Pittsburgh Pirates outfielder Casey Stengel. When Stengel returned home to Kansas City, he reportedly recommended Moore, and a few of his teammates, to J.L. Wilkinson. Stengel would later say that, “Moore was one of the best shortstops that will ever live!”

Once relieved of military duty, Dobie Moore joined the Monarchs midway through their inaugural season, and was immediately a star! A consistent contact hitter who possessed rare slugging power at the position, Moore batted .300 or better in all seven seasons with Kansas City. In 1924, he led the Negro National League in both batting average and doubles. Moore was notoriously a great “bad-ball hitter” with teammate Newt Allen claiming, “There were no bad pitches for him.” On the field, Moore’s slick fielding earned him the moniker, “The Black Cat” with teammate George Sweatt praising his “rifle arm”. Rumor has it that Moore had a penchant for mischief, occasionally tugging at the belts of opposing baserunners as they circled the bags.

In 1926, Moore got off to an unbelievable start, batting over .400 through 17 games. However, his career came to a sudden end that season due to an incident that is still shrouded in mystery. In what became his final game with the club, he recorded two hits in an extra innings win over the New York Cubans. That night, he was shot in the leg at the home of Elsie Brown. Many allege that Brown was Moore’s mistress, while others claim her “home” was a brothel. Moore claimed that she mistook him for a prowler, and Brown initially corroborated the story before accusing Moore of abuse. It is believed that Moore jumped from a second-story window to escape further harm. Whether it was the gunshot, the fall, or both, Moore broke his leg in six places and was never able to play baseball again.

WHY THIS GUY? In 1954, Tom Baird, then owner of the Kansas City Monarchs, selected his own all-time Monarchs team. Having seen the likes of Ernie Banks, Jackie Robinson, and Willie Wells play for his ballclub, he still named Dobie Moore as the greatest shortstop in team history. It’s been said many times that Moore and Newt Allen were the greatest double play combo in the Negro Leagues, but I would love to see what Moore and Robinson could do together! Some say that if not for the injury, Moore would be thought of as the greatest shortstop in Negro Leagues history. The numbers seem to support this. Seamheads calculated Moore’s all-time WAR (Wins Above Replacement), based on a 162 game season, to be 8.7 - the highest ever recorded for a shortstop. That’s a full win higher than Honus Wagner and Willie Wells. Moore’s WAR is actually identical to the great Barry Bonds!

MONARCHS MOMENT In Game 6 of the 1924 Colored World Series, the Kansas City Monarchs trailed three games to one (Game 3 had been ruled a tie after 13 innings). In that fateful game at Muehlebach Field, Dobie Moore recorded three hits in four at-bats and scored two runs. The Monarchs would win the game 6 - 5 and go on to the win the nine-game World Series, five games to four.

OTHERS CONSIDERED: Ernie Banks (Kansas City Monarchs: 1950, 1953), Willie Wells (Kansas City Monarchs: 1932), Jackie Robinson (Kansas City Monarchs: 1945), Ted Strong (Kansas City Monarchs: 1937 - 1939, 1941 - 1942, 1946 - 1947)

“At third base, your team captain, #3, NEWT ALLEN!”

3B | #3 | Newt Allen

Kansas City Monarchs (1923 - 1944)

Newt Allen, 1934

PAINTING BY: Graig Kreindler, from the collection of Jay Caldwell.

Nickname(s): “Colt”, “The Black Diamond”

Other Notable Teams:

Awards: SECOND TEAM: 1952 Pittsburgh Courier All-Time Negro League Team (UTIL INF), Tom Baird’s 1954 All-Time Kansas City Monarchs Team (2B)

All-Star Nods: 6x East-West All-Star (NgL)

Rings: 8 (1924 Colored World Series Champion, 1942 Negro World Series Champion, Negro National National League Champion - 1923 & 1929, Negro American League Champion - 1937, 1939, 1940, & 1941)

Hall of Fame:

Bats: Right Throws: Right

Batting Average: .288

Homeruns: 21

Runs Batted In: 476

Hits: 1,053

Stolen Bases: 140

Runs: 612

ONCE UPON A TIME: In The Soul of Baseball, author Joe Posnanski revealed Buck O’Neil used to carry around a list of players he believed belonged in the Hall of Fame. Near the top of that list was Newt Allen, who O’Neil regarded as the greatest second baseman in the history of the Negro Leagues. “He could make all the plays around the bag,” O’Neil once wrote, “and I have never seen a second baseman with as good an arm.” Teammate Chet Brewer recalled that, “Newt used to catch the ball, throw it up under his left arm; it was just a strike to first base. He was something! Got that ball out of his glove quicker than anybody you ever saw.”

A graduate of Lincoln High School, Newt Allen cut his teeth on the sandlots of Kansas City. Monarchs owner J.L. Wilkinson first took notice of Allen when he was playing semi-professionally for the Omaha Federals. Wilkinson signed Allen first to his All Nations team, and then called him up to the Monarchs for the 1923 season. In 1924, Newt Allen helped the Monarchs win the first-ever World Series among Negro Leagues teams. He batted .282 in the series and recorded 11 hits, seven of which were doubles. At that time, Allen’s teammates had taken to calling him “Colt”, due to him being the youngest player on the team. When Newt Allen helped the Monarchs win a second World Series title in 1942, he was anything but.

Allen’s former teammate, and the manager of that 1942 team, Frank Duncan once remarked that, “I have watched Newt Allen play for over twenty years, and I still get a thrill when I know he’s going to put on that uniform.” Reportedly, New York Giants manager John McGraw lamented being unable to purchase Allen’s contract in the late 1920s, describing him as, “one of the finest infielders, white or colored, in organized baseball.” A career Monarch, and team captain for most of his tenure, Newt Allen helped Kansas City win nine pennants and two Negro League World Series titles. He remains the only person listed among Buck O’Neil’s “All-Time Negro League All-Stars” who has not been inducted in baseball’s Hall of Fame.

WHY THIS GUY? The question isn’t as much, “Why Newt Allen?” as it is, “Why Newt Allen at third base?” It’s clear that he was an extremely gifted middle infielder. In 1952, when the Pittsburgh Courier conducted their poll of the all-time great Negro Leaguers, Newt Allen finished second among second basemen. The guy who beat him out? Jackie Robinson, my starter at second base. When people describe Allen’s play, they consistently mention his slick fielding, incredible speed, and super strong arm. Buck O’Neil remarked many times that Allen had “a shortstop’s arm” which perfectly suits him to man the hot corner. By the late 1930s, Newt Allen had made this transition and he was playing third when the Monarchs won the Series in ‘42. It may seem odd to play Allen anywhere but second, but it was even tougher leaving a Monarchs’ third base mainstay, another Newt, off the roster entirely.

FUN FACT: In 1925, Newt Allen completed an unassisted triple play! Allen also has the distinction of playing in the first-ever Colored World Series in 1924 and the first-ever Negro League World Series in 1942. His Kansas City Monarchs won both.

OTHERS CONSIDERED: Walter “Newt” Joseph (Kansas City Monarchs: 1922 - 1935), Dobie Moore (Kansas City Monarchs: 1920 - 1926), Hank Thompson (Kansas City Monarchs: 1943, 1946 - 1948)

All paintings shown in the player profiles were painted by Graig Kreindler (www.graigkreindler.com, @graigkreindler), and are from the collection of Jay Caldwell. These paintings, and more, were on display at the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum (NLBM) in Kansas City, Missouri in 2020 for the celebration of the centennial of the founding of the Negro National League. They were displayed there again in 2022. The NLBM hopes to bring them back to KC on a permanent basis in the future.

Jay Caldwell initiated the project of honoring Negro Leagues players by bringing them to life through colored portraits for the Negro Leagues’ Centennial. He was fortunate when Graig Kreindler enthusiastically agreed to support this effort with his special artistic talent, and research on the colors of Negro Leagues uniforms. Graig and Jay continue to collaborate on projects to this day.

“In left field, #8, TURKEY STEARNES!” [7]

LF| #8 | Norman “Turkey” Stearnes

Kansas City Monarchs (1931, 1934, 1938 - 1940)

Turkey Stearnes, 1931

PAINTING BY: Graig Kreindler, from the collection of Jay Caldwell.

Nickname(s): “Turkey”, “The Gobbler”, “The Black Ty Cobb”

Other Notable Teams: Detroit Stars (1923 - 1931), Chicago American Giants (1932 - 1935, 1937 - 1938)

Awards: 7x National League Homerun Leader (NgL), 6x National League Triples Leader (NgL), 2x National League Batting Champion (NgL), ROLL OF HONOR: 1952 Pittsburgh Courier All-Time Negro League Team (OF), Michigan Sports Hall of Fame (2008), Tennessee Sports Hall of Fame (2010)

All-Star Nods: 5x East-West All-Star (NgL)

Rings: 3 (1932 Negro Southern League Champion, Negro American League Champion - 1939 & 1940)

Hall of Fame: 2000 (USA)

Bats: Left Throws: Left

Batting Average: .348

Homeruns: 187

Runs Batted In: 1,009

Hits: 1,326

Stolen Bases: 130

Runs: 917

ONCE UPON A TIME: By many accounts, they called him Turkey because of the way he circled the bases, bobbing his head and flapping his arms. Others say it was the southpaw’s pigeon-toed batting stance, wide-open with his right heel twisted and big toe pointing straight up, that earned him the moniker. Norman “Turkey” Stearnes claimed the nickname was from his childhood when the otherwise slender centerfielder had a potbelly. Regardless of origin, “The Gobbler” was one of the most electrifying players in the history of the Negro Leagues. Satchel Paige said that, “[Turkey Stearnes] had a funny stance, but he could get around on you. He was one of the greatest hitters we ever had. … He was as good as anybody who ever played baseball.”

Despite his unorthodox running style, Turkey was known for his explosive speed both on the bases and as a defender, able to make the largest outfields seem small. He was enigmatic, often carrying around his collection of bats in a special case. Buck O’Neil recalled that, “He talked to his bats like they were his children.” He would chastise them for poor performances and even sleep with one after it had a great day at the plate. Often, the days were great. Turkey’s combination of swing and power made him “one of the Negro Leagues’ most feared hitters”. He was an extremely lethal lead-off hitter, leading the league in triples six times and batting .300 or better in 15 of his 18 seasons in the Negro Leagues. He also recorded more home runs in the Negro Leagues than anyone, including the great Josh Gibson. Of his long balls, Turkey Stearnes once said, “I hit so many, I never counted them. And I’ll tell you why. If they did not win a ball game, they didn’t amount to anything.”

Stearnes spent much of his career playing for the Detroit Stars. After the Detroit Stars folded in 1931, he joined the Monarchs for the first time. He would spend the 1930s jumping from one team to the next before playing the final three seasons of his career in a Kansas City uniform. The legendary Cool Papa Bell once said, “If Turkey is not in the Hall of Fame, then no one deserves to be in the Hall of Fame.” In 2000, Stearnes was finally inducted. In 2019, the Detroit Tigers honored him with a plaque in their Walk of Heroes. In 2020, the field at Hamtramck Stadium, the former home of the Detroit Stars, was renamed in his honor.

WHY THIS GUY? In his biography, Monarchs’ great Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe named Turkey Stearnes as the left fielder in his own personal all-time team of Negro Leaguers, calling him, “one of the greatest ballplayers that ever played. He hit the ball as far as Josh [Gibson] and often … he had as much power as anyone who ever played. He was fast, too. Willie Mays, nobody could play any more outfield.” It speaks volumes that even though the East-West All-Star Game did not exist until Turkey was in his 30s, he was still named to the game five times! He’s top ten all-time in both career batting average and career slugging percentage. He was an elite five-tool player and one of the greatest centerfielders to ever play. Getting to have his bat in the line-up, his speed on the bases, and his skills in left field made this an easy decision.

MONARCHS MOMENT: On June 6, 1939 at National Park in St. Louis, Turkey Stearnes went 5-for-5 at the plate, and was credited with 9 putouts, in a game against the St. Louis Stars. The Monarchs won by a score typically reserved for football games, 21 - 13.

OTHERS CONSIDERED: Willard “Home Run” Brown (1937 - 1944, 1946 - 1951), Elston Howard (Kansas City Monarchs: 1948 - 1950)

“The centerfielder, #15, COOL PAPA BELL!” [8]

CF | #15 | James “Cool Papa” Bell

Kansas City Monarchs (1932)

Cool Papa Bell, 1929

(shown here with Petroleros del Cienfuegos, a Cuban Winter League team)

PAINTING BY: Graig Kreindler, from the collection of Jay Caldwell.

Nickname(s): “Cool Papa”

Other Notable Teams: St. Louis Stars (1922 - 1931), Pittsburgh Crawfords (1933 - 1937), Homestead Grays (1943 - 1946)

Awards: SECOND TEAM: 1952 Pittsburgh Courier All-Time Negro League Team (CF), Washington Nationals Ring of Honor, 1998 Sporting News “Baseball’s 100 Greatest Players” (#66), 2020 The Athletic “Baseball 100” (#84)

All-Star Nods: 8x East-West All-Star (NgL)

Rings: 7 (Negro League World Series Champion - 1943 & 1944, Negro National League Champion - 1928, 1930, 1931, 1935 & 1936)

Hall of Fame: 1974 (USA)

Bats: Both Throws: Left

Batting Average: .325

Homeruns: 57

Runs Batted In: 596

Hits: 1,548

Stolen Bases: 285

Runs: 1,152

ONCE UPON A TIME: Cool Papa Bell was so fast, Buck O’Neil wrote, “he could hit the light switch and be in bed before the room went dark.” Cool Papa was so fast, Double Duty Radcliffe said, “If he bunts and it bounces twice, put it in your back pocket.” Cool Papa Bell was so fast, Satchel Paige recalled, “One time he hit a line drive right past my ear. I turned around and saw the ball hit him sliding into second.” Cool Papa Bell was so fast that Pie Traynor worried, “He’d steal a pitcher’s pants” when he got on base. Cool Papa Bell was so fast, some say, he once scored from first on a sacrifice bunt. Bell himself claimed he was so fast that he stole 175 bases in a 1933 season where he played 180 to 200 games. Cool Papa Bell was so fast that even gold medalist Jesse Owens refused to race him.

James “Cool Papa” Bell began his career as a pitcher with the St. Louis Stars. His manager, Bill Gatewood, gave him his nickname his rookie year after he struck out the famed Oscar Charleston in a tight spot. Gatewood was also the one to move Bell to the outfield, recognizing the need to get Bell’s bat, and legs, in the line-up more often. Bell was a switch hitter who regularly batted above .300. His speed on the bases and in the outfield was nearly mythical. Satchel Paige claimed, “he was just the best fielder you ever saw. He could grab that ball no matter where it was hit.” Perhaps most impressive of all was Bell’s acumen. He had a deep understanding of the game only made him more dangerous as a base-runner. Bell led the Stars to three Negro National League titles in four years.

After the Negro National League, and the St. Louis Stars, disbanded in 1931, Bell joined the Monarchs for half a season before moving on to the Pittsburgh Crawfords, and then the Homestead Grays. Cool Papa Bell later returned to the Monarchs, first as a player for the B team and later as that team’s manager. It was as a coach, where Bell had his greatest contributions to the Monarchs. He is credited with discovering Ernie Banks and teaching Jackie Robinson how to play second. But before all that, he spent nearly 30 years as one of the toughest outs in professional baseball. Baseball pioneer Bill Veeck said that, “Cool Papa was one of the most magical players I’ve ever seen.”

WHY THIS GUY? I will be the first to point out that of all the guys on this roster, Cool Papa Bell was a Monarch for the least amount of time. He essentially had a cup of coffee with the team in 1932, which is enough for me to nab him for this Monarchs team! With Cool Papa Bell, we are talking about probably the fastest guy to ever play the game. He was once clocked circling the bases in 12 seconds! By comparison, the modern day record is 13.85. Bell routinely led the Negro Leagues in stolen bases and walks. It’s not just about the speed though. Cool Papa could hit, he could field, and yes, he could run. It was a tough choice between putting him or Turkey Stearnes in centerfield, but luckily, I get to see both speedsters shag fly balls for the Monarchs.

MONARCHS MOMENT: When Cool Papa Bell was rooming with Satchel Paige on a barnstorming trip with the Monarchs B Team, he noticed there was an electrical short in their hotel room. It caused a delay of a couple seconds between the light being switched off and the light bulb actually turning off. This gave Bell the idea to wager Paige that he could turn out the lights and get into bed before the room went dark. As Buck O’Neil would later write, “It cost [Satchel] fifty bucks to learn that Cool Papa Bell was faster than the speed of light.”

OTHERS CONSIDERED: Norman “Turkey” Stearnes (Kansas City Monarchs: 1931, 1934, 1938 - 1940), George Altman (Kansas City Monarchs: 1955)

“Playing right field, #39, CRISTÓBAL TORRIENTE!” [9]

RF | #39 | Cristóbal Torriente

Kansas City Monarchs (1926)

Cristóbal Torriente, 1923

(shown here with the los Elefantes de Marianao team of the Cuban League)

PAINTING BY: Graig Kreindler, from the collection of Jay Caldwell.

Nickname(s): “The Babe Ruth of Cuba”, “Carlos”

Other Notable Teams: Club Almendares Blues (1913 - 1927), Chicago American Giants (1918 - 1925), Detroit Stars (1927 - 1928)

Awards: 1920 National League Batting Champion (NgL), 2x Cuban Winter League Batting Champion, FIRST TEAM: 1952 Pittsburgh Courier All-Time Negro League Team (RF)

All-Star Nods:

Rings: 9 (Negro National League Champion - 1920, 1921, & 1922, Cuban League Champion - 1912, 1914, 1916, 1920, 1925, 1926)

Hall of Fame: 1939 (Cuba), 2006 (USA)

Bats: Left Throws: Left

Batting Average: .340

Homeruns: 55

Runs Batted In: 532

Hits: 759

Stolen Bases: 93

Runs: 471

ONCE UPON A TIME: Cristóbal Torriente’s contemporaries called him “The Babe Ruth of Cuba”, but when Ruth visited Cuba in 1920, Torriente stole the spotlight. That winter, Ruth was barnstorming with the New York Giants in Havana. During a game between the Giants and Almendares Blues on November 5, Torriente hit three inside-the-park homeruns. At one point, Ruth pitched in an attempt to stop the Almendares’ onslaught. With two men on, Torriente ripped a bases-clearing double to left center. Ruth later remarked that if Torriente “could play with me in the Major Leagues, we would win the pennant by July.”

Cristóbal Torriente’s legend blends myth and math. Some details, like the Alemendares vs. Giants series, are well-documented, while others live on as stories from those who saw him play. Frankie Frisch claimed Torriente’s grounders left craters in the infield. It’s said the stocky Cuban outfielder had a bat that could hit any pitch over any fence in any park. Indianapolis ABC’s manager, C.I. Taylor, said of Torriente, “There walks a ballclub”, likening his talent to an entire roster’s.

During the 1920s, Torriente played in both Cuba and the Negro National League, helping Rube Foster’s Chicago American Giants win three consecutive league titles. Known for his excellent defense, incredible speed, and consistency at the plate, Torriente also had a fiery temper that led to altercations with teammate, opponents, and especially umpires. His behavior, coupled with night life indulgence, caused Foster to trade him to Kansas City before the 1926 season.

In his lone season with the Monarchs, Cristóbal Torriente was the Monarchs’ leader in batting average (.352) and on-base percentage (.439), leading the team to a first-half championship. Torriente abruptly left the team mid-season over a dispute with team owner J.L. Wilkinson about a missing diamond ring, likely costing the Monarchs the second-half title. He returned for the League Championship Series, batting .407 over the nine games, but the Monarchs ultimately lost the series to Chicago, four games to five. Forever a legend in Cuba, Torriente was inducted in their inaugural Hall of Fame class in 1939.

WHY THIS GUY? I’ll let his Hall of Fame plaque do the talking. “A compact and powerful five-tool player with tremendous extra-base power to all fields.” Defensively, Torriente could cover lots of ground, had an excellent glove, and an absolute cannon for an arm. On the base paths, he was as dangerous as anyone. At the plate, he hit consistently, and with power. Torriente spent nine seasons in the Negro Leagues and hit over .300 in eight of them! Fellow Cuban Martín Dihigo was quoted in Miami Herald as saying, “Cristóbal Torriente is the best Cuban player I have ever seen, the most complete before my eyes.” This seemed an obvious choice - a standout centerfielder with a right fielder’s arm. On a selfish sidenote, if his temper was as ridiculous as they say, I would love to see one bad call go against Torriente just so I could see the reaction.

MONARCHS MOMENT: In the 1926 Negro National League Championship Series, Cristóbal Torriente faced his former team, the Chicago American Giants. In Game 1, he went 2-for-4 with both of his hits being doubles. The Monarchs would win the game 4 - 3 with Torriente’s lone RBI being the difference.

OTHERS CONSIDERED: Hurley McNair (Kansas City Monarchs: 1920 - 1927, 1934), Wilber “Bullet” Rogan (Kansas City Monarchs: 1920 - 1930, 1933 - 1938), Bob Thurman (Kansas City Monarchs: 1949)

“The designated hitter, #10, HOME RUN BROWN”

DH | #10 | Willard “Home Run” Brown

Kansas City Monarchs (1937 - 1944, 1946 - 1951)

Willard Brown, 1942

PAINTING BY: Graig Kreindler, from the collection of Jay Caldwell.

Nickname(s): “Home Run”, “Sonny”, “Willie”, “Ese Hombre (That Man)”

Other Notable Teams: St. Louis Browns (1947)

Awards: 7x American League Batting Champion (NgL), 1947 American League Batting Champion (NgL), 6x American League Home Run Champion (NgL), 2x Triple Crown Winner (Puerto Rican Winter League)

All-Star Nods: 8x East-West All-Star (NgL)

Rings: 5 (1942 Negro League World Series Champion, Negro American League Champion - 1937, 1939, 1940, 1941)

Hall of Fame: 1996 (Caribbean), 2006 (USA)

Bats: Right Throws: Right

Batting Average: .351

Homeruns: 54

Runs Batted In: 391

Hits: 580

Stolen Bases: 80

Runs: 332

ONCE UPON A TIME: On July 20, 1947, Willard Brown made history at Sportsman’s Park. When him and fellow Monarch Hank Thompson took the field for the St. Louis Browns, they became the first black teammates to appear in a Major League Game. Less than a month later, “Home Run” Brown hit an inside-the-park home run in a pinch-hit at-bat against the Detroit Tigers. It was the first home run by a black player in American League history. After hitting the homer, Brown’s teammate Jeff Heath smashed the bat Brown had used. Upon his signing, the Associated Press considered Brown to be the “prize package of the lot” of MLB signees from the Negro Leagues. A week after the historic home run, Brown was released by St. Louis after only 21 games, and returned to Kansas City.

Before his brief stint in the Majors, Brown spent ten seasons as a star outfielder with the Kansas City Monarchs, where he was one of the league’s premier sluggers. Manager Buck O’Neil called him, “the most natural ballplayer I ever saw. He’d steal second base standing up.” Adding that, “He once hit a home run on a ball that had bounced in the dirt.” His raw power and tape-measure shots caused Josh Gibson to nickname him “Home Run”. His teammates, however, had another nickname for him.

“He loved to play on sunny days and before big crowds,” Monarchs’ catcher Sammy Haynes once shared. “That why we called him Sonny.” Willard Brown was such a gifted athlete that many felt he could play as well as he wanted to on any given day. On days where the stands were full and the sun was out, Brown seemed unstoppable. When the fans weren’t there or the skies were gray, Brown was more prone to take it easy or even not play at all. O’Neil wrote, “He used to carry around a Readers Digest in his hip pocket to give him something to do out in center field.”

After his pit stop in St. Louis, Brown would play for the Kansas City Monarchs for another four seasons, while also playing winter ball in Puerto Rico. Brown found his swing again in the winter of 1947, batting .432 with 27 home runs and 86 RBIs, good enough for the league’s Triple Crown. Two winters later, he did it again, earning him another nickname from fans in Puerto Rico: “Ese Hombre”. While Brown never got another shot at the Majors, those who saw him play knew he was indeed “That Man”.

WHY “THAT MAN”? When Josh Gibson names you, “Home Run”, that means something. What Turkey Stearnes was to the 1920s and Josh Gibson was in the 1930s, Willard Brown was to the 1940s. Speaking of Josh Gibson, Brown is tied with Gibson as the only players to lead the Negro Leagues in batting average five times. Brown also led the league in homers six times! He led the Negro Leagues in extra base hits 8 times! (A feat only matched by Hank Aaron in the Major Leagues) Remember why Brown’s teammates called him “Sonny”? Well the Sunday I’m envisioning would be the sunniest of them all. Perfect weather, a sold out park, and the kind of day where the bat of Home Run Brown would not be silenced. As the Designated Hitter, he can flip through his Readers Digest from the dugout, so long as when the time comes, him and his hefty 40 ounce bat are ready for action.

MONARCHS MOMENT: In the sixth inning of Game 5 of the 1946 Negro League World Series, Willard Brown hit a two-run double, and the Kansas City Monarchs took a 3 - 2 lead in the series. Despite a great series from Brown, the Monarchs would drop the next two games and lose the series to the Newark Eagles.

OTHERS CONSIDERED: Norman “Turkey” Stearnes (Kansas City Monarchs: 1931, 1934, 1938 - 1940), Ernie Banks (Kansas City Monarchs: 1950, 1953), Wilber “Bullet” Rogan (Kansas City Monarchs: 1920 - 1930, 1933 - 1938)

Learn more about the Kansas CIty Monarchs, and all of the Negro Leaguers who helped build the bridge that led to the integration of baseball, and society. Plan your visit to the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum today!

“Today’s starting pitcher for your Kansas City Monarchs is #25, BULLET ROGAN!”

SP | #25 | Wilber “Bullet” Rogan

Kansas City Monarchs (1920 - 1930, 1933 - 1938)

Bullet Rogan, 1924

PAINTING BY: Graig Kreindler, from the collection of Jay Caldwell.

Nickname(s): “Bullet”, “Bullet Joe”, “Cap”

Other Notable Teams: 25th Infantry Wreckers (1915 - 1920), All Nations (1917)

Awards: 3x National League Homerun Champion (NgL), 3x National League Complete Games Leader (NgL), 3x National League Stolen Bases Leader (NgL), 2x National League Wins Leader (NgL), 2x National League Strikeouts Leader (NgL), 2x National League Shutouts Leader (NgL), 1921 National League ERA Leader (NgL), FIRST TEAM: 1952 Pittsburgh Courier All-Time Negro League Team (P), ROLL OF HONOR: 1952 Pittsburgh Courier All-Time Negro League Team (OF), Tom Baird’s 1954 All-Time Kansas City Monarchs Team (P), 2020 The Athletic “Baseball 100” (#92)

All-Star Nods: 1x East-West All-Star (NgL)

Rings: 4 (1924 Colored World Series Champion, Negro National League Champion - 1923 & 1929, 1937 Negro American League Champion)

Hall of Fame: 1998 (USA)

Bats: Right Throws: Right

Win-Loss Record: 120 - 52

Earned Run Average (ERA): 2.65

Strikeouts: 918

Complete Games: 136

Shutouts: 18

ONCE UPON A TIME: In 2018, Shohei Ohtani burst onto the scene with his dual talent as a pitcher and power-hitter. The sports media hastily compared him to Babe Ruth, mostly overlooking a player with similar two-way brilliance from that same era: Wilber “Bullet” Rogan. Rogan made his mark as a dominant pitcher and slugger for the Kansas City Monarchs. Satchel Paige said of Rogan, “He was the onliest pitcher I ever knew, I ever heard of in my life, was pitching and hitting in the cleanup place.”

Before joining the Monarchs, Bullet Rogan made his name with the U.S. Army’s 25th Infantry Wreckers. It was there, in 1918, that Casey Stengel first saw him, calling him, “one of the best, if not the best, pitcher that ever pitched.” Many credit Stengel with recommending Rogan to Monarchs’ owner J.L. Wilkinson but Rogan had already pitched for Wilkinson’s All Nations while on furlough in 1917. In 1920, Wilkinson brought Rogan to Kansas City.

With his high-octane, lively fastball, Bullet Rogan quickly became the premier pitcher in the Negro National League (NNL). Though the fastball earned Bullet his nickname, it was his varied arsenal that made him so dangerous. Bob Kendrick, president of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, said, “He threw the kitchen sink at you. He threw forkballs. He threw spitballs. He was a master of the palm-ball.” Batters feared Rogan’s curveball, which broke so sharply, hitters often could not react in time. Babe Herman of the Brooklyn Dodgers called it, “one of the best curveballs I ever saw.”

Rogan was just as lethal at the plate. He regularly batted cleanup for the Monarchs, leading the NNL in both home runs and stolen bases multiple times. “If you saw Ernie Banks in his prime,” Buck O’Neil said, “then you saw Rogan.” His versatility didn’t end there - he played all three outfield positions when not pitching. In 1929, at nearly 40, Rogan led his winter ball team to a win against Major League All-Stars, led by Jimmie Foxx and Al Simmons. The Chicago Defender reported, “The Stars merely blinked at his many offerings as they streaked across the plate.”

Rogan led the Monarchs to four pennants and their first World Series title in 1924. He later spent time as player-manager and umpired in the Negro Leagues. Baseball’s first two-way superstar went unrecognized for decades. Dizzy Dean remarked, “[Rogan] should be in the Hall of Fame.” In 1998, Rogan was finally inducted. His son, Wilber Rogan, Jr., spoke on his behalf, stating, “When Satch [Paige] was on the mound, he needed a designated hitter. When my dad was on the mound, he was in the cleanup spot.”

WHY THIS GUY? Frank Duncan, who caught them both said, “If you had to choose between Rogan and Paige, you’d pick Rogan because he could hit.” Judy Johnson, “Satchel Paige was fast, but Rogan was smarter.” Newt Allen similarly favored Rogan over Paige on account of Rogan’s intelligence on the mound. Those endorsements are good enough for me! He was the first two-way superstar of American professional baseball. He was the ace of a dominant Monarchs’ pitching staff, and he was batting clean-up in a deadly line-up. In the famed 1952 Pittsburgh Courier poll, he was named a pitcher, and he received votes for being an all-time outfielder. By some accounts, he is top five in all-time Negro Leagues batting average. He’s the winningest pitcher in Negro Leagues’ history. I can’t bench Home Run Brown on a Sunday, but I wish the Designated Hitter rule permitted me to bat him in place of a position player so I could place Rogan in the line-up. Then again, it’s my game. If I can bend the rules of space and time, why can’t I do the same with the DH rule?

MONARCHS MOMENT: In the 1924 Colored World Series, Bullet Rogan led the Kansas City Monarchs to victory over the Hilldale Athletic Club (Daisies). During the series, Rogan pitched in four games, played outfield in seven, and batted in all ten. On the mound, he went 2 - 1 with a 2.89 ERA, and struck out 13 batters. As a fielder, he recorded eight assists and 14 putouts. At the plate, he led the team with 14 hits and a .389 batting average. He also had four stolen bases, four runs scored, and eight runs batted in as the Monarchs became the Negro Leagues’ first World Series champs.

OTHERS CONSIDERED: Leroy “Satchel” Paige (Kansas City Monarchs: 1940 - 1942, 1944 - 1947), John Donaldson (Kansas City Monarchs: 1920 - 1924, 1934), Hilton Smith (Kansas City Monarchs: 1936 - 1948)

Hilton Smith, 1948

PAINTING BY: Graig Kreindler, from the collection of Jay Caldwell.

Nickname(s): “Smitty”

Other Notable Teams:

Awards: 4x American League Strikeout Leader (NgL), 3x American League Wins Leader (NgL), 1938 American League Triple Crown Winner (NgL)

All-Star Nods: 6x East-West All-Star (NgL)

Rings: 5 (1942 Negro League World Series Champion, Negro American League Champion - 1937, 1939, 1940, & 1941)

Hall of Fame: 2001 (USA)

Bats: Right Throws: Right

Win-Loss Record: 70 - 38

Earned Run Average: 2.92

Strikeouts: 594

Complete Games: 62

Saves: 11

ONCE UPON A TIME: “Those are the real heroes,” Dave Winfield once said. “Hilton Smith, guys that played in the Negro Leagues, never got a chance in the Major Leagues. But you kept on playing.” While the tragedy of baseball’s color line relegated some of the game’s greatest talents to the shadows, Kansas City Monarchs pitcher Hilton Smith was often overshadowed on his own team.

In the late 1930s, Hilton Smith was the Monarchs’ ace. Between 1937 and 1940, he led the league in strikeouts three times and wins twice. In 1938, he won the Triple Crown. He was a four-time East-West All-Star. When Satchel Paige joined the team in 1941, Smith remained the ace, going 25 - 1, again leading the league in wins and strikeouts, and earning an All-Star nod. Yet, despite his accomplishments, he picked up the unfortunate nickname “Satchel’s Relief”.

“We never told him,” Buck O’Neil once said, “but Hilton was the best pitcher we had, including Satchel.” In those days, Satchel Paige was the headliner. His larger-than-life personality, flamboyant antics, and blazing fastball brought in the fans. To maximize Paige’s gate appeal, the Monarchs regularly pitched him for two to three innings before handing the ball to Smith to finish out the game. Roy Campanella once said of the two pitchers, “My God. You couldn’t tell the difference.”

But, there was a difference. While Paige relied on showmanship and hard throwing, Smith had versatility and remarkable control, along with breakneck speed. In his expansive arsenal of pitches, one stood out. “He had one of the finest curveballs I ever had the displeasure to try and hit,” said Monte Irvin. “Sometimes you knew where it would be coming from, but you still couldn’t hit it.” Armed with “the best sweeping curveball in Negro Leagues history”, Hilton Smith won 20 or more games in 12 consecutive seasons, leading the Monarchs to five pennants and a World Series win in 1942.

After he retired, Hilton Smith stayed close to baseball. He was a scout for the Chicago Cubs, and coached youth teams locally. Among those teams was one for Safeway (grocer) that featured a young Frank White. The standout Kansas City Royals infielder credited Hilton Smith with encouraging him to try out for the Royals. While baseball forgot about Hilton Smith for far too long, he never forgot about the game.

WHY THIS GUY? Buck O’Neil believed, “From 1940 to 1946, Hilton Smith might have been the greatest pitcher in the world.” Smith’s resume seems to support this notion. By all accounts, Smith was a great teammate. He was routinely called upon to provide long relief, and excelled in doing so. The man went 6-1 in exhibition games against Major League All-Stars. He went undefeated in league play twice! When it gets late in the game, his collection of pitches, particularly that curveball, are the last thing any batter wants to see. Not only do I feel great about Smitty replacing Rogan on the mound, but with a lifetime batting average above .300, he could also slide into Rogan’s spot in the line-up on days he bats.

MONARCHS MOMENT: In his first-ever home game for the Monarchs on May 16, 1937, Hilton Smith pitched a no-hitter against the Chicago American Giants. It’s said that only two balls left the infield during his dominant performance. Kansas City defeated Chicago 4 - 0.

CP | #92 | “Famous” John Donaldson

Kansas City Monarchs (1920 - 1924, 1934)

John Donaldson, 1915

(shown here with the All Nations team)

PAINTING BY: Graig Kreindler, from the collection of Jay Caldwell.

Nickname(s): “Famous”, “Cannonball”, “The Colored Wonder Pitcher”, “Smoke”

Notable Teams: All Nations (1912 - 1918, 1920 - 1923)

Awards: FIRST TEAM: 1952 Pittsburgh Courier All-Time Negro League Team (P), Tom Baird’s 1954 All-Time Kansas City Monarchs Team (CF), Missouri Sports Hall of Fame (2017)

All-Star Nods:

Rings: 2 (1924 Colored World Series Champion, 1923 Negro National League Champion)

Hall of Fame:

Bats: Left Throws: Left

Win-Loss Record: 6-9

Earned Run Average: 4.14

Strikeouts: 69

Complete Games: 9

Saves: 2

ONCE UPON A TIME: In the barnstorming era of the 1910s, newspapers referred to “Famous John Donaldson” so often that many fans assumed “Famous” was his first name. Ironically, the man once hailed by The Kansas City Sun as “the greatest pitcher in the country, black or white” is largely forgotten today, even among hardcore baseball fans. Donaldson’s story has been neglected by history, and much of it remains unknown.

What is known is that in 1915,, New York Giants manager John McGraw was impressed by Donaldson, saying, “I think he is the greatest [pitcher] I have ever seen”. McGraw added that if not for baseball’s racial barrier, he would pay $50,000 for Donaldson’s contract and consider it a bargain. He even offered the light-skinned Donaldson $10,000 to change his name and pose as a Cuban to bypass the league’s policy. Donaldson refused, later saying, “It would have meant renouncing my family.”

At the time, Donaldson had been pitching for the All Nations, an integrated barnstorming outfit out of Des Moines, for four seasons. Fans came from far and wide to see the rocket-armed southpaw. One account said, “He threw as fast as a cannonball could shoot it.” More than a fastball hurler, Buck O’Neil credited Donaldson with throwing the slider decades before anyone else did. In May of that year, Donaldson had a stretch where he pitched 30 consecutive no-hit, no-run innings! In every town he visited, the papers sang his praises. The Grand Forks Daily Herald called him “the greatest moundsman outside the big leagues.”

When Donaldson was 29, All Nations owner J.L. Wilkinson signed him to the Kansas City Monarchs in the newly created Negro National League. Donaldson was an instant star, both on the mound and as a centerfielder. After four seasons in KC, Donaldson returned to the more lucrative barnstorming circuit. Over the next 20 years, Donaldson pitched in nearly 700 towns across the United States and Canada. As both a player and a showman, he set a standard for all black barnstormers to follow.

Donaldson never stopped paving the way. In 1949, he joined the Chicago White Sox as the first black full-time scout in Major League history. He quit a few years later, frustrated by the club’s lack of interest in signing young black talent. After declining his recommendations to sign Willie Mays and Hank Aaron, the final straw was when the team passed on Ernie Banks, allowing him to sign with their cross-town rivals.

WHY THIS GUY? Since John Donaldson was largely resigned to barnstorming through small town middle America, it does call into question the level of competition he faced at times. Yet, the fact that J.L. Wilkinson considered John Donaldson the greatest pitcher to ever don a Monarchs’ uniform is quite telling. He clearly had an eye for pitching talent! The known statistics are staggering! His 14 no-hitters are twice Nolan Ryan’s Major League record! His 5,081 career strikeouts are second only to Ryan. His 413 wins trail only Cy Young and Walter Johnson. His run of 30 consecutive no-hit, no-run innings is something that will never be seen again. (Seriously, how is this guy not a Hall of Famer!?) He had speed, he had touch, and he kept batters guessing. I nearly named him the starter because, by all accounts, he was THAT good. When it’s time to slam the door, there is no doubt Donaldson is the guy I want to see heading to the mound.

FUN FACT: Kansas City Monarchs’ owner J.L. Wilkinson credited John Donaldson for suggesting the name “Monarchs” for his newly-formed Negro League franchise in 1920.

OTHERS CONSIDERED: Chet Brewer (Kansas City Monarchs: 1925 - 1935, 1937, 1940 - 1941, 1946), José Méndez (Kansas City Monarchs: 1920 - 1926), Andy Cooper (Kansas City Monarchs: 1928 - 1929, 1931 - 1939), Connie Johnson (Kansas City Monarchs: 1940 - 1942, 1946 - 1950), Bill Foster (Kansas City Monarchs: 1931), Booker McDaniel (Kansas City Monarchs: 1940 - 1946, 1949)

UTIL | #6 | José Méndez

Kansas City Monarchs (1920 - 1926)

José Méndez, 1909

(shown here with Almendares of the Cuban League)

PAINTING BY: Graig Kreindler, from the collection of Jay Caldwell.

Nickname(s): “El Diamante Negro” (“The Black Diamond”), “The Black Christy Mathewson”

Notable Teams: Club Almendares Blues (1908 - 1921), All Nations (1913 - 1917)

Awards: ROLL OF HONOR: 1952 Pittsburgh Courier All-Time Negro League Team (P), ROLL OF HONOR: 1952 Pittsburgh Courier All-Time Negro League Team (UTIL INF), Tom Baird’s 1954 All-Time Kansas City Monarchs Team (UTIL)

All-Star Nods:

Rings: 2 (1924 Colored World Series Champion, 1923 Negro National League Champion)

Hall of Fame: 1939 (Cuba), 2006 (USA)

Bats: Right Throws: Right

Win-Loss Record: 30 - 9

Earned Run Average: 3.46

Strikeouts: 139

Complete Games: 16

Saves: 8

Batting Average: .232

Homeruns: 3

Runs Batted In: 62

Hits: 144

Stolen Bases: 62

Runs: 86

ONCE UPON A TIME: A Washington Post article from 1912 explained the struggles of Major League teams playing winter ball in Cuba, noting, “… strong defense has been the stumbling block to our teams cleaning up in Cuba and the biggest individual obstacle in their path down there has been José Méndez …” The article dubbed the flame-throwing right hander, the “black Christy Mathewson.” Mathewson’s own manager, John McGraw, agreed, describing Méndez as, “… sort of Walter Johnson and Grover Cleveland Alexander rolled into one.” In 1911, Méndez triumphed in a duel with Mathewson. Afterwards, the Hall of Fame hurler called Méndez “a great pitcher” and expressed that if Méndez were white, “… he’d be the star of the leagues up there in no time.”

One of the first shining stars of Cuban baseball, José Méndez baffled big league batters with his dominating fastball, breaking curve, and devastating change-up. He was a slick fielder, often encouraging his infielders to play closer to the foul lines as he was capable of covering the heart of the infield. Between 1908 and 1913, the Cuban star posted a 1.85 ERA in 24 contests against Major League teams. His greatest performance came in 1908, when he pitched 25 innings against the Cincinnati Reds without allowing a single run. Philadelphia Athletics catcher Ira Thomas said, “It is not alone my opinion but the opinion of many others who have seen Méndez pitch that he ranks with the best in the game.” The Cuban fans who saw the hard-throwing phenom dubbed him, “El Diamante Negro”, or “The Black Diamond.”

In the same way American teams came to Cuba in the winter, he came stateside in the summer. In 1913, Méndez joined the All Nations barnstorming team. The next year, an injury to his throwing arm threatened to disrupt his career, but Méndez transitioned to shortstop. Ira Thomas praised his fielding and hitting ability noting, “… his hitting is hard and timely.” In 1920, he joined the Kansas City Monarchs. In 1923, he was named the team’s player-manager. That year, Méndez re-discovered his pitching form. He pitched 138 innings that season, going 12 - 4, leading the league with a 1.89 ERA.

In 1924, he split time between shortstop and pitcher, going 4-0 on the mound, and led the Monarchs to the first-ever Colored World Series, against the Hilldale Athletic Club. Méndez appeared in 4 games, notching a 2 - 0 record, as the Monarchs won the championship, 5 - 4. He played two more season in Kansas City before retiring to Cuba. A player who amazed those who watched him, and a gentleman beloved by those he managed, The Black Diamond’s legacy endures in the annals of both American and Cuban baseball.

WHY THIS GUY? The fact that Méndez received votes for both pitcher and utility infielder during the famed Pittsburgh Courier poll in 1952, tells you everything you need to know about his versatility as a player. I threw him in the bullpen because he was a pitcher first, and that’s where he was at his best. His pitching ability is a key part of what makes him the ultimate utility. He was accomplished on the mound, but could also play second, third, and shortstop. With Willard Brown, John Donaldson, and Bullet Rogan, the team already has an incredible amount of outfield depth. The addition of José Méndez gives the team depth nearly everywhere else. Deciding between Méndez and Ted Strong at utility was one of the toughest choices I had to make. Ultimately, Méndez’s pitching ability, as well as his important place in Monarchs’ history, made him the choice for me.

MONARCHS MOMENT: On October 20, 1924, José Méndez, who was fresh off surgery, ignored the advice of doctors and named himself the starting pitcher for Game 10 [12] of the inaugural Colored World Series. In a masterful performance, Méndez gave up only three hits in a nine-inning shutout performance. As a batter, he added a hit and scored a run. The Monarchs defeated Hillsdale Club 5 - 0, securing their first World Series title.

OTHERS CONSIDERED: Ted Strong (Kansas City Monarchs: 1937 - 1939, 1941 - 1942, 1946 - 1947), Sam Bankhead (Kansas City Monarchs: 1934)

“The Kansas City Monarchs are managed by Buck O’Neil.“

MGR | #22 | John Jordan “Buck” O’Neil

Kansas City Monarchs, Player (1938 - 1943, 1946 - 1955)

Kansas City Monarchs, Manager (1948 - 1955)

Buck O’Neil, 1942

PAINTING BY: Graig Kreindler, from the collection of Jay Caldwell.

Nickname(s): “Buck”, “Nancy”, “Foots”, “Cap”

Notable Teams: Memphis Red Sox (Player 1937) Chicago Cubs (Coach 1962 - 1964, Scout 1955 - 1988)

Awards: 2x American League Batting Champion (NgL), Tom Baird’s 1954 All-Time Kansas City Monarchs Team (1B), Tom Baird’s 1954 All-Time Kansas City Monarchs Team (MGR), Chicago Cubs Hall of Fame

All-Star Nods: 2x East-West All-Star (NgL), 1x Northern League All-Star (MiLB)

Rings: 5 (1942 Negro League World Series Champion, Negro American League Champion - 1939, 1940, 1941, & 1953)

Hall of Fame: 2022 (USA)

Managerial Record: 63-32-2

Winning %: .660

ONCE UPON A TIME: Ernie Banks said, “I patterned my life after Buck O’Neil,” often crediting O’Neil with teaching him how to play baseball. Joe Posnanski wrote that, “[O’Neil would disagree,] Ernie Banks knew how to play, but what he did learn [from me] was how to play the game with love.” When Billy Williams nearly quit the Cubs, O’Neil famously reminded him of his passion for the game. Lou Brock said, ”He touched the heart of everyone who loved the game.” Ichiro Suzuki said of his friend, “... you can see and tell and feel he loved this game.” When O’Neil appeared on Ken Burns’ Baseball in 1994, enrapturing millions of viewers, the Kansas City Star proclaimed, “A Star is Born …. At 82.” Fair to say, John Jordan “Buck” O’Neil taught a lot of people how to love baseball.

As a boy, O’Neil’s uncle took him to see the Chicago American Giants play the Indianapolis ABC’s. An avid baseball fan, O’Neil regularly pored over the box scores of his favorite Major Leaguers. That day, however, he saw a more exciting version of the game than he had ever seen, played by people who looked like him. Seeing Rube Foster and Oscar Charleston on the diamond made O’Neil realize baseball was possible for him.

At 25, O’Neil entered the Negro Leagues, spending a year with the Memphis Red Sox before the Kansas City Monarchs purchased his contract. He starred at first base, winning two batting titles, making a pair of All-Star appearances, and helping the Monarchs win the 1942 Negro League World Series. He became the team’s manager in 1948, when Major League Baseball was beginning to open the doors to players of color. O’Neil had an obligation to both win games and develop young talent that could be sold to the Majors. Three-time All-Star George Altman recalled, “He was a tremendous manager. … He was very encouraging and a good baseball man. … I just loved playing for him …” In 1955, O’Neil joined the Chicago Cubs as a scout, credited with signing Ernie Banks, Lou Brock, Lee Smith , Oscar Gamble, Andre Dawson, and Joe Carter. In 1962, the Cubs made him the first black coach in MLB history. After two seasons, he returned to scouting for Chicago. In 1988, he joined the Kansas City Royals in a similar role.

O’Neil never stopped spreading the gospel of the Negro Leagues. In 1990, he was approached about starting a Negro Leagues Hall of Fame in Kansas City. However, O’Neil insisted on a Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, believing the greatest Negro Leaguers belonged in Cooperstown. His advocacy helped nine Negro League players get inducted into baseball’s Hall of Fame. His campaigning led to a special election by the Hall in 2006 where 17 more players, coaches, and contributors were elected. O’Neil was not among them. Despite this, he traveled to Cooperstown to speak on behalf of the inductees. Lou Brock said, “Somebody’s got to be around to tell that story. I think [O’Neil] has been preserved for that purpose.”

It seems Brock was right. A few months later, O’Neil passed away at 94. In 2022, O’Neil finally joined the Hall of Fame. While many felt it was years too late, O’Neil himself would have likely claimed that he, “was right on time.”

WHY THIS GUY? As much as I have referenced the late, great Buck O’Neil throughout this piece, his inclusion should not come as a surprise. While recent generations recall him as the greatest ambassador that the Negro Leagues, and the game of baseball, ever had, that minimizes his greatness. As Buck would often remind people, “I could play!” He was an exceptional scout with an eye for talent. His baseball knowledge and ability to build relationships with the players made him a great manager for the Monarchs, and inspired the Cubs to make him the MLB’s first black coach. The common thread throughout these stories has been accounts from O’Neil. He saw nearly every one of these Monarchs play. He played with or managed several of them. I do not think I would be able to contain my excitement seeing #22 in the dugout, and I know that ol’ Buck would be best-equipped to get the very best out of each player.

MONARCHS MOMENT: On April 25, 1943, in a road game against the Memphis Red Sox, Buck O’Neil went four-for-four at the plate. In his first at-bat, he doubled. Second time around, he singled. On the third at-bat, he hit the ball over the left field fence. On his fourth hit, which bounced off the right field fence, O’Neil refused to run home on a probable inside-the-park home run. Staying on third, he completed the cycle. That same night in Memphis, he met Ora Lee Williams, his future wife. “That was my greatest day,” O’Neil later said, “Easter Sunday, 1943. I hit for the cycle and met my Ora.”

FUN FACT: Buck O’Neil appeared in the 2006 Northern League All-Star Game as a member of the then Kansas City T-Bones. At 94 years old, he became the oldest player to make a plate appearance in a professional game. In 2021, the T-Bones rebranded to the Kansas City Monarchs, making O’Neil the only player to have suited up for both iterations of the team.

OTHERS CONSIDERED: Frank Duncan (Kansas City Monarchs: 1942 - 1947), José Méndez (Kansas City Monarchs: 1920, 1923 - 1925)

Like Hall of Famer Rogers Hornsby, I too dream of baseball in winter. Unlike Hornsby, I dream of all the Monarchs greats who once called old Muehlebach Field home. PHOTO CREDIT - disKCovery

“That’s the thing about baseball, if you think about it. Yesterday comes so easy.”

On May 9, 2014, I was with some friends in Arlington to watch the Texas Rangers take on the Boston Red Sox. Perennial All-Star Yu Darvish was on the hill in a game I’ll never forget.

On that fateful night, Hall of Famer David Ortiz broke up Darvish’s bid for a perfect game with two outs in the seventh inning. Then, with two away in the ninth, Ortiz finished the job and broke up the no-no as well. In the decade since, I have not come anywhere near as close to witnessing perfection as I did that day.

I think a lot about that game. It’s a story I often tell. It always begins as a tale of frustration but when the story ends, I always crack into a smile.

If I can bend the rules of space and time, the DH rule should be no issue. IMAGE CREDIT - disKCovery

There are so many parts of that story I never do tell. It was such a beautiful evening in Texas, truly ideal baseball weather. I had not seen any of the friends I went to the game with in years. While we all stay in touch, that was still the last time the four of us were in the same place together. I chuckle thinking about how many fans left after the Rangers took an 8-0 lead in the sixth, clearly unaware of what was going on. I wasn’t going to tell them. In baseball, there’s just some things we don’t talk about.

While the ending was not what we wanted, we were so fortunate to have chosen THAT game. A day earlier or a day later, and the outcome would not be nearly so memorable.

In the annals of baseball history, that game will never be regarded as perfect. But for me, the memory of it always will be.

That’s the beauty of this sport. Perfection is attainable on the field. Far more often, it’s achieved off of it, in the hearts and minds of the fans who love it so.

In my own mind, perfection comes into focus. I can see the Monarchs of a bygone era warming up as only they knew how. Dobie Moore dives to his right to field an imaginary hard-hit chopper in the gap. He flips the “ball” to Jackie Robinson who leaps over a phantom slider and completes the well-orchestrated, pantomime double play by hurling empty air over to Ernie Banks at first. Getting to see these players at this place on this day? That would truly be perfect.

Well … almost perfect.

These guys can’t play shadow ball all day! They need an opponent. What team could ever hope to match up against these Monarchs? Who would even be worthy of occupying the third base dugout at Muehlebach Field for this game?

That’s a fantasy for another day.

TO BE CONTINUED…

Those Pesky Endnotes That I Often Insist Upon

There are so many incredible and iconic Monarchs’ looks to choose from, but this is the one I see. Perhaps, I should just have had each Monarchs’ player wear the best uniform of their era, similar to how the East-West All-Star Game and the Major League Baseball All-Star Game once had each player don their own uniform. Then again, I really do love that 1945 uni made famous by Jackie Robinson. CLICK HERE TO RESUME READING

I am well aware that traditionally, the visiting team’s lineup is announced first. I also am aware that this “basketball-style” announcement is typically reserved for full-roster announcements in postseason games. But, what can be bigger than this? This is a game for Kansas City. It’s a moment for the Monarchs, so selfishly, I’m announcing the home team first. CLICK HERE TO RESUME READING